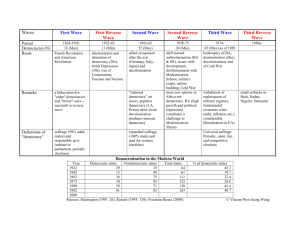

In Search of Democratic Peace: Problems and Promise

advertisement