Incentive Plan Design Principles

advertisement

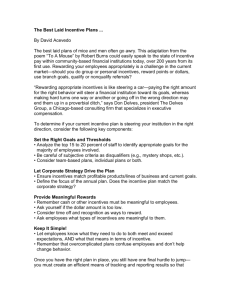

Test Your Incentive Plans Against These Design Principles By J. Timothy O’Rourke, CCP President and Chief Executive Officer Matthews, Young – Management Consulting If your Company ever had an Incentive Plan that failed to get the desired results, it may have been a problem with the design. On the other hand, if your Company has never used incentive compensation, but it is considering using it for the first time, then understanding the “do’s and don’ts” will help avoid the mistakes many Companies have made. In any case, the principles discussed here have been developed through Matthews, Young – Management Consulting’s 29 years of experience designing and supporting all types of incentive plans. First, let’s look at how incentive compensation fits into the total compensation picture. We picture total compensation as a pyramid. At the base of the pyramid is the base salary component, that “guaranteed annuity” which defines to a large degree the standard of living. Next, the benefit package takes care of our employees’ family needs, health and welfare both now and in retirement. Perquisites support our ability to get our jobs done and provide some personal utility as well. These components will be the subject of other articles in the future. But here we are going to focus on bonuses and incentives. Let’s define these terms. While “bonus” and “incentive” are used interchangeably in the press and in everyday discussions, for our purposes, we’ll define the pure “bonus” as a payment that is made after something good happens, but that was not promised in advance. It’s a complete surprise! Now, let’s define an incentive as a payment that is promised in advance of a performance period, and in return for a specific, objectively measurable performance. Components of Total Compensation The bonus, as defined above, will make an employee feel good about your Company as an employer for a short period of time. It may also reinforce the behavior that caused you to make the reward, especially if you communicate why you granted the bonus clearly. However, because the bonus was discretionary and not promised again, it will not cause a repetition of the behavior you rewarded for a very long period of time. In our experience, bonuses have a place in the total compensation mix, but the Company should not spend a great deal of money for bonuses, because they do not motivate like incentives. They are safe, but not very powerful. If a bonus can be thought of as a “shovel,” an incentive can be thought of as a “bulldozer.” It is a much more powerful form of compensation in its ability to focus performance. Like a bulldozer, incentives can be powerfully constructive or powerfully destructive in the hands of an inexperienced operator. The following principles suggest the lessons learned from years of operating incentive plans: Principals of Incentive Design Principle #1 – The potential incentive must be big enough to get the employees’ attention. I am often asked if I really believe that incentives make employees work harder. I do not believe that incentives make employees work harder, but I know that well designed incentives make most employees focus. Good employees already work hard, but hard working employees who are not focused often work against the results the Company seeks. Incentives create focus. But, you have to get employees attention first. The amount required to get one individual’s attention may be different than the amount required to make the next person focus. For one thing, each of us is motivated to differing degrees by different types of rewards. We all like feedback from superiors, but some personality types are more motivated by praise than others. In the same vein, the opportunity for financial rewards motivates some more than others. Because of, and in spite of this dilemma, your incentive plan will have a greater chance of success if you carefully define what the size of the opportunity must be in order to get the majority of your employees’ focus. Principle #2 – The performance or results required to earn the incentive must be within the employees’ control or significant influence. In our experience, this one principle has led to the failure or success of more incentive plans than any other principle. One must be able to see or understand the cause and effect relationship between one’s effort, the results of that effort and the reward. This principle explains why a profit sharing plan is more like a bonus than an incentive for many employees. Unless an employee is in a position to impact profits to a huge degree, they will not see the connection between their work and the reward from a profit sharing plan. The fact of the matter is, during hard times, when profits are under pressure and therefore profit sharing plans are less likely to be funded, good employees often work harder or smarter than at times when profits are easy to improve. A clerk may significantly improve his or her productivity during such times, but their unit of output may have little direct impact on profits. The first time this clerk contributes more of the results over which he or she has control and gets less or no profit sharing, the incentive aspects of the profit sharing plan are dead as far as that clerk is concerned. This is not to say that profit sharing plans are no good. But, it does say that it is important to recognize what a profit sharing plan is…. a bonus plan. The need to provide the proper “line of site” between output and rewards at all levels of the organization may require a large number of different incentive plans to cover all employees under incentives. The administrative requirements then become burdensome, and we have seen diminishing returns from an effort to cover an everincreasing number of levels in the organization. On the other hand, we have seen successful applications of different mixes of compensation components for different levels of the organization. Principle #3 – The performance or results required to earn the incentive must be perceived as achievable with “stretch.” If I told you that I would give you a million dollars at the end of the next year, I would probably get your attention. And, your next question would be “What do I have to do to get it?" Then, if I told you that you would need to get yourself to Mars and back by the end of next year, I would lose your attention. No matter how good the promised reward, the employee must believe that the desired performance is achievable. Of course, Principle #2 described above has a great deal to do with the employee’s perception of the ability to achieve the desired outcome. We have also found that the objective must be perceived to require a stretch. If I told you that you could earn that million-dollar incentive if the paint on the walls of an empty storage room remained the same color all year, you would probably focus on the objective for a while. However, after some time, you might begin to doubt that I would really pay you for such a meaningless objective. Then, you would get bored with the effort and realize that, if I was not lying to you, the objective was too easy to achieve and you would stop watching the walls. The incented performance needs to be perceived as a desirable, stretch goal to get and keep the employee’s attention. Principle #4 – The payout must be worth the effort required to “stretch.” This may seem obvious and the same issue as Principle #1, but this principle suggests that the Plan should pay something for partial achievement of the desired outcome. Not only must the potential incentive be big enough to get the employees’ attention, but also it must be perceived to be worth the effort. If the effort or focus required to get the full incentive opportunity requires stretch, in other words it’s seriously at-risk, then the actual payout after the final measurement is made needs to justify the attempt that was made to achieve the full objective. Many plans fail because they have a “cliff” where any level of achievement below the objective pays nothing. “Cliffs” encourage employees to do anything to achieve the last few units of measurement. If they are close to achieving the stretch objectives, they might do something you do not want to happen to get over the cliff. One CEO with a cliff plan lamented that he was afraid the employees would sell the furniture at year-end to achieve a tough revenue objective. The way to avoid cliffs is to define a range of performance for which paying some incentive is justified. The line between the “start pay point” and the “full pay point” can be a straight line for simplicity or a curved line for increasing or decreasing incentives as certain hurdles are achieved. At every point in the range of achievement, though, the payout must be perceived to be worth the required effort. Principle #5 – The payout should never be a surprise. This principle often differentiates an incentive from a bonus as defined at the beginning of this article. If the payout can not be forecast as the performance period proceeds, the Plan will fail to keep the employees focus on the desired outcome. Furthermore, the first time that the desired outcome is achieved, and the employer fails to pay the incentive, the motivational power of the Plan is lost forever. Principle #6 – The sources of performance tracking must be readily and frequently available. In order for the Plan to avoid surprises, the Plan must pay for the achievement of objective measures of the desired outcomes. Too much subjectivity in the measurements will turn a Plan into a surprise bonus. Furthermore, the participants in the Plan need to know where they stand at all times. Therefore, the sources of the measurements should be available to every participant on a regular basis. Principle #7 – Calculations for determining payouts must be simple and clearly understood. The “KISS” principle applies to incentive plans as much as in any endeavor, if not more so. The key question to ask is, “Do my employees know where they stand at any point in time during the performance period?” In order to keep the employees focused, they need to know where, precisely, they stand and how much they are leaving on the table. This principle argues against formulas that create curvilinear payouts and plans that use more than a few measures of success. As a practical matter, we have found that employee focus decreases geometrically as the number of incentive plan measurements exceeds seven. This is an observed phenomenon and not a scientifically proven maximum. However, it tends to pass the common sense test with our clients. Principle #8 – Finally, you will get what you pay for, so be sure it is what you really want. Incentive plans are powerful forms of compensation. Well-designed plans focus employees much more than any other component of reward systems. Many a management team has driven their company in the wrong direction because they rewarded the wrong outcomes. Before you even consider incentives, make sure you know the company’s strategy and the critical measurements of success. These are the primary principles our firm has learned over almost 30 years of designing incentive plans at all levels in many industries. They are basic enough to be applied to any and all types of incentives, short-term, longterm, cash and “non-cash,” current and deferred, management and staff.