Best Training Practices Within the Software Engineering Industry

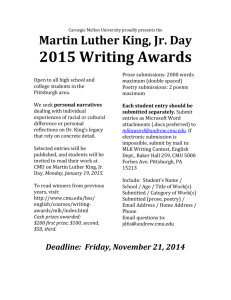

advertisement