TABLE OF CONTENTS - American Society of Golf Course Architects

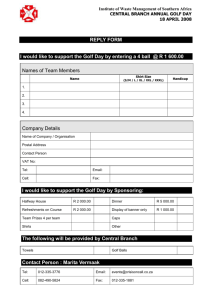

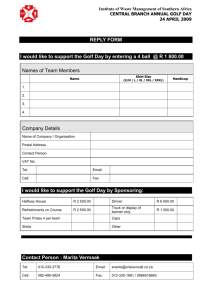

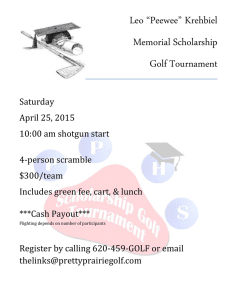

advertisement