Valuation of Physical Non-Current Assets at Fair

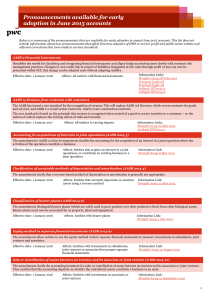

advertisement