Labor and Birth at Risk

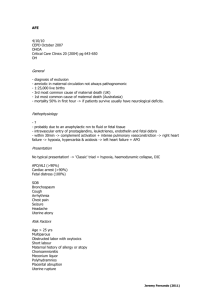

advertisement