A Language and Literacy Framework for Bilingual Deaf Education

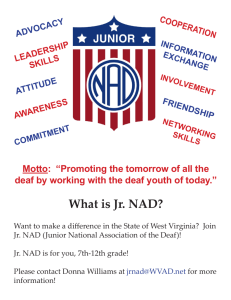

advertisement