Oedipus Trilogy Resources : Primarily Rex and Colonus

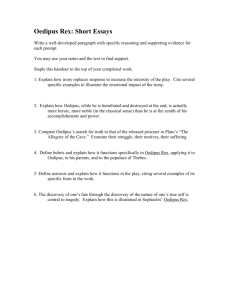

Here are just a few of the resources you can find about the Oedipus Trilogy ( Oedipus

Rex , Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone ). Shmoop.com has information on Antigone as well; I suggest that at some point AFTER YOU HAVE READ it, you check it out. Please keep in mind that any resources you find for Antigone and The Odyssey should be in addition , not in place of, reading the texts.

I have left all hotlinks in place in case you want to use the .doc or .pdf to follow the information. The .pdf version should work on any e-reader. http://www.shmoop.com/oedipus-the-king/

Oedipus the King

In A Nutshell

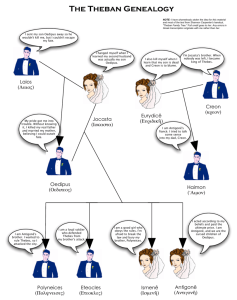

Sophocles is considered one of the great ancient Greek tragedians. Among Sophocles' most famous plays are Oedipus the King , Oedipus at Colonus , and Antigone . These plays follow the fall of the great king, Oedipus, and later the tragedies that his children suffer. The Oedipus plays have had a wide-reaching influence and are particularly notable for inspiring Sigmund Freud

’s theory of the "Oedipus Complex," which describes a stage of psychological development in which a child sees their father as an adversarial competitor for his or her mother’s attention (or in non-psychology speak, it’s the kill-the-father-sleep-with-the-mother complex).

The three plays are often called a trilogy, but this is technically incorrect. They weren't written to be performed together. In fact they weren't even written in order. Antigone , which comes last chronologically, was the play Sophocles wrote first, around 440 B.C. It wasn't until about 430 B.C that Sophocles produced his masterpiece Oedipus the King .

He finally wrote Oedipus at Colonus in 401 B.C., near the end of his life. Also note that the plays were rarely if ever revived during the playwright's life time, so it's not like it would have been easy for Sophocles' audiences to compare them.

These facts probably explain some of discrepancies found in the plays. For example, while Creon is the undisputed King at the end of Oedipus the King , in Oedipus at

Colonus it’s Polyneices and Eteocles who are battling for the throne. In

Antigone , Creon assumes the throne with no mention of the fact that he's ever sat on it before. It's pretty unlikely that Sophocles forgot this key fact. But it could very well be that it just didn't

matter very much. Each play is a separate interpretation of the myth, not a part of a trilogy. Sophocles would've been under no obligation to make the plays coherent in every detail.

Of course, while the plays aren't technically a trilogy and do have discrepancies, they do share many similarities. Several of the key characters put in repeat appearances, including Oedipus, Creon, Teiresias, Ismene, and Antigone. Also, the plays have a lot of the same themes. The plays all deal in some way with the will of man vs. the will of the gods. Self-injury and suicide also plague the family until the end. It seems that

Oedipus's family is never quite capable of escaping the pollution of his terrible mistakes.

Why Should I Care?

Stop us if you've heard this one before: guy walks into a bar, meets Han Solo , almost macks on his sister, steps up to save a galaxy, and finds out by the end of the second movie that his greatest enemy is *gasp* his father ! Well, it's a familiar tale, not just for all moviegoers post-1977

– but also for all theatergoers after, say, 429 B.C.

Take out that bit about Han Solo (and also, maybe the bar), and change sister to mother and you've got the bare bones of Sophocles 's Oedipus the King : guy gets chosen as the

One to battle evil (sadly, not a host of stormtroopers; Sophocles goes with a plague caused by the evil presence of a murderer in Thebes), macks on his mother, and finds out that he himself was his father's killer without even knowing it.

Our point is: it seems kind of bizarre to us now to believe absolutely in fate. But all of

Sophocles's characters believe in it, to the point where the father of this truly dysfunctional family (King Laius) is willing to order his infant son (Oedipus) killed when a prophecy tells him that his son will be his murderer. And all of the father's efforts to prevent his own death don't work. Why? Because it's fate : these characters have no real control over their own lives. Just like it's fate that Luke meets Leia and then Darth

Vader .

The neat thing about fate in both Oedipus the King and Star Wars works is that, really, these guys don't have any control over their own lives

– because they're fictional. After all, what kind of character development would there be if Darth Vader was defeated without knowing he was Luke's father? Would Darth Vader ever have **spoiler alert**

been redeemed at the end? The relationship has to come out, or else there'd be no narrative after the first movie.

Oedipus marries his mother by accident, and if they were allowed to just hang around staying married and living in blissful ignorance, what would Sophocles be telling his audience? Nothing anyone would want to hear outside of Jerry Springer . So fate comes in to make sure we learn a lesson: marrying your mother and killing your father is so wrong that it will bring plague to your city and make you tear your own eyes out in horror. And in a way, maybe all fiction is about fate, even today: after all, fictional characters can’t avoid what their authors lay out for them.

Oedipus the King Summary

How It All Goes Down

King Oedipus, aware that a terrible curse has befallen Thebes, sends his brother-in-law,

Creon, to seek the advice of Apollo . Creon informs Oedipus that the curse will be lifted if the murderer of Laius, the former king, is found and prosecuted. Laius was murdered many years ago at a crossroads.

Oedipus dedicates himself to the discovery and prosecution of Laius’s murderer.

Oedipus subjects a series of unwilling citizens to questioning, including a blind prophet.

Teiresias, the blind prophet, informs Oedipus that Oedipus himself killed Laius. This news really bothers Oedipus, but his wife Jocasta tells him not to believe in prophets, they've been wrong before. As an example, she tells Oedipus about how she and King

Laius had a son who was prophesied to kill Laius and sleep with her. Well, she and

Laius had the child killed, so obviously that prophecy didn't come true, right?

Jocasta's story doesn't comfort Oedipus. As a child, an old man told Oedipus that he was adopted, and that he would eventually kill his biological father and sleep with his biological mother. Not to mention, Oedipus once killed a man at a crossroads, which sounds a lot like the way Laius died.

Jocasta urges Oedipus not to look into the past any further, but he stubbornly ignores her. Oedipus goes on to question a messenger and a shepherd, both of whom have information about how Oedipus was abandoned as an infant and adopted by a new family. In a moment of in sight, Jocasta realizes that she is Oedipus’s mother and that

Laius was his father. Horrified at what has happened, she kills herself. Shortly thereafter, Oedipus, too, realizes that he was Laius’s murder and that he’s been married to (and having children with) his mother. In horror and despair, he gouges his eyes out and is exiled from Thebes.

Oedipus the King Oedipus the King Summary

Oedipus emerges from his palace at Thebes. Outside are a priest and a crowd of children. Oedipus is the King, in case you didn’t get that from the title. Everyone else is, in short, "suppliant."

Oedipus has heard rumors that a curse is afflicting Thebes. After briefly congratulating his own greatness, he asks the priest what’s up.

The priest responds that basically everything that could be wrong in the city is wrong: crops are dying, cattle are dying, people are dying, and there's generally low morale.

Because Oedipus is the boss man, the priest asks him to please take care of this mess.

We learn that Oedipus has saved the city once before by lifting a curse put on it by the Sphinx.

Oedipus reveals he already knew that the city was in a bad state, so he sent his brother-inlaw, Creon, to Apollo (or at least to Apollo’s oracle) to get more information.

In the midst of this conversation, Creon returns with news from Apollo.

Creon tells Oedipus that Apollo told him that in order to lift the curse on the city, the men that murdered the city’s former king, Laius, must be banished or killed.

Well, where was the criminal investigation unit when the murder went down?

Turns out the Sphinx had previously warned against inquiring into the murder.

Talk about mixed signals. So thus far, no one’s busted out the cavalry to hunt the murderers down.

Oedipus repeatedly congratulates himself and promises to deal with the murderers and save the city.

Everyone exits except the Chorus, an ever-present group of wise and gossipprone observers. They, unfortunately, do not sing.

The Chorus then recounts the multiple problems the city faces including infertility, plague, famine and no one’s Xboxes are working. The lamentation is split into two voices, the "Strophe" and the "Antistrophe." This is a Greek tool where the

Chorus is made up of two halves so it can sort of converse with itself. Like a duet made of lots of people. Anyway, the Chorus begs for help.

Oedipus reenters and demands that anyone with information about the former king's murder speak up. He curses the murderer.

The Chorus responds that they know nothing and suggest Oedipus ask the blind prophet, Teiresias (which we think is a major case of irony) for his knowledge.

Oedipus, ever-prepared, informs the Chorus that, quite conveniently, Teiresias is already on his way.

Teiresias shows up immediately.

Oedipus briefly explains to him the c ity’s situation and Apollo’s advice. Then

Oedipus asks for help.

Teiresias says with great foreboding (and foreshadowing), "You do NOT want to hear what I have to say." Roughly speaking, anyway. Teiresias continues to insist that it is better for him to leave rather than speak.

Oedipus, however, demands that Teiresias tell him what he knows.

Oedipus works himself into an angry rage and then busts out an insult we think you should add to your personal repertoire: "You would provoke a stone!." Oh, diss.

Teiresias grumbles "fine" and reveals that Oedipus himself was the one who killed the former king.

Then Oedipus says, "What? I didn’t hear you."

Teiresias tells him for the second time.

Most mysterious of all, according to Teiresias, Oedipus is committing "the worst of sins" with the people "he loves the most." More foreshadowing. Teiresias tells

Oedipus that he is a threat to himself, in the "stop asking questions" kind of way.

Oedipus responds that he thinks Teiresias and Creon are simply framing him in order to seize the throne. He then taunts Teiresias about his blindness, which is not only politically incorrect but makes him out to be a total jerk.

The Chorus freaks out and tells the men they aren’t solving anything by arguing.

Let’s just call them "reality-check Chorus."

Teiresias tells Oedipus he’s majorly, grossly cursed and will end up blinded, poor, and alone. This is the worst psychic reading ever. He then casually mentions Oedipus’s parents and informs Oedipus that he "shall learn the secret" of his marriage.

Then, right before he leaves, he says (in cryptic language) that Oedipus is married to his mother. Well, he says that Oedipus is "a son and husband both," which maybe isn’t so cryptic after all, unless you’re Oedipus.

The Chorus talks about the fight between Oedipus and Creon. The Strophe says whoever he is, the murderer needs to get out of Thebes, and fast. The

Antistrophe which, don’t forget, is made up of the city’s citizens, declares that it can’t believe Oedipus is at fault until they see the glove on his hand, so to speak.

Both halves of the Chorus agree that they have no idea whether or not to believe

Teiresias.

Creon arrives, having overheard that Oedipus accused him of conspiring to steal the throne. Rumor, apparently, travels almost as fast in Thebes as in high school.

Oedipus enters again and accuses Creon to his face. Creon wants the opportunity to respond, but Oedipus won’t shut up.

Finally, Creon gets a word in. He explains that, as Oedipus’s brother-in-law, he has everything he could want without any of the stress of being in charge.

Basically, no one wants to shoot the Vice President. In ancient Greece.

Oedipus continues to make accusations and says he’ll have Creon killed.

Jocasta, Oedipus’s wife and Creon’s sister, comes in. She is horrified at her husband and brother’s fighting, and also at the death threat.

Jocasta and the Chorus urge Oedipus to listen to Creon’s honest appeals and spare his life.

Creon storms off.

Jocasta asks Oedipus what’s going on. He explains he’s been accused of killing

Laius. He leaves out the "you might be my Mom" part.

Jocasta responds that such prophecies are ridiculous. As an example, Jocasta says that her son by Laius was prophesized to kill his father, but that they killed the child as a baby to prevent it. Plus, Laius was killed by foreign highway robbers, none of which could possibly have been his son.

Oedipus, hearing the story, flips out. Suddenly, he worries that he might be the murderer after all. He asks Jocasta lots of questions about th e murder’s whereabouts and other details.

Confused, Jocasta reveals that one of Laius’s servants survived the incident at the crossroads.

Oedipus insists that the servant be summoned for questioning.

Oedipus tells Jocasta that as a child, a man once told him that his mother and father were not his real parents. It was also prophesized that he would kill his father and sleep with his mother.

The plot is thickening considerably.

Oedipus also reveals that he killed several men in a small incident at a cross roads. Oops. He hopes to find out from the servant whether the King’s murderers were many or just one man. Oedipus utters the incredibly wise statement, "One man can not be many." Well, now we know why this guy is king.

In other words, he’s saying if it was a sole murderer, that will confirm his guilt.

(You know, in case the repeated prophecies, overwhelming evidence, and sinking stomach feeling were not enough).

Jocasta reminds Oedipus that even if he did kill Laius, he is not Laius’s son, since their only child was killed.

The Chorus pleads with the gods for mercy.

Jocasta, completely frazzled, makes an offering to the gods and prays for

Oedipus to keep his temper and wits.

The Chorus asks a lot of questions, mostly revolving around the one big question of "what is going on?"

Conveniently, a messenger shows up from Corinth and informs Jocasta and

Oedipus that Oedipus’s father, the King of Corinth, has died of natural causes.

Jocasta interprets the King’s natural death as proof that the prophecy about

Oedipus killing his father was false. Phew.

Jocasta pulls an, "I was right and you were wrong," and Oedipus is all, "Yeah, yeah, I know."

Oedipus, however, is still worried about the sleeping with his mother part of the prophecy. Jocasta tells Oedipus that if he just stops thinking about it, it will go away. We wish this still worked today.

The messenger questions Oedipus about the prophecy and his fears. The messenger tells Oedipus that the King of Corinth (Polybus) and his wife, Merope, were not Oedipus’s real parents. Unable to have a child themselves, they adopted Oedipus. Yet another "uh-oh" moment.

Turns out, Oedipus (as an infant) was given to the messenger with his feet pierced and tied. This is apparently why he is named "Oedipus," which means

"screwed-up foot" in Greek (roughly speaking).

The messenger got the infant Oedipus from a shepherd who, conveniently, is still alive and within bellowing distance of the rest of our cast.

Jocasta urges quite energetically that Oedipus drop the issue before he discovers more than he bargained for.

Oedipus says, "No," and insists on his talking to the shepherd.

Jocasta makes reference to seeing Oedipus for the last time and runs off wailing.

Oedipus assumes she’s ashamed of his low birth (since as an infant he was found in some rather raggedy swaddling clothes) and vows to set things right.

The old shepherd shows up.

Oedipus questions the old shepherd. Like Teiresias, this guy refuses to speak.

Oedipus has his servants twist the old man’s arms to try to force him to talk.

The man folds like a bad poker hand, revealing that Jocasta was the mother of the child that he discovered and gave to the messenger. Jocasta wanted the child taken away because it had been prophesized that the boy would kill his father and sleep with his mother.

FINALLY, Oedipus pieces things together and realizes that Jocasta is his mother.

As predicted by the prophecy, he has slept with his mother and killed his father.

Oedipus runs out, saying, quite eloquently, "O, O, O."

The Chorus, expectedly, laments the tragedy.

Another messenger arrives and announces that Jocasta, disgusted with herself for sleeping with her own son, has hung herself. She’s dead.

Oedipus finds that he has lost both his wife and mother. He very dramatically rushes to her dead body, tears the broaches from her dress (which have sharp, phallic pins on them) and gouges out his eyes.

Oedipus staggers outside all bloody and gross.

The Chorus is startled (understatement of the year) and feels bad for him

(understatement of the century).

Oedipus explains that he gouged his eyes out because there was no longer anything pleasant for him to see. We’re just amazed that the man can manage to stand around and explain things at this point.

Oedipus asks the Chorus to help send him out of Thebes or kill him. He wishes he had died as a child.

Creon enters and Oedipus asks to be sent away. Oedipus feels it is his fate to stay alive so that he can suffer.

Oedipus asks Creon to take care of his daughters, but not his sons because they can take care of themselves.

Creon leads Oedipus out of the room while Oedipus continues to beg for his exile.

Oedipus

Character Analysis

The Mystery of Oedipus's Hamartia

You could wallpaper every home on Earth with the amount of scholarly papers written on Oedipus. OK, that's a bit of an exaggeration. But, in truth, there is a whole lot of disagreement about one central aspect of Oedipus's character. Scholars have been talking smack to each other for centuries over an essential question: what is Oedipus's hamartia , often called a tragic flaw? Aristotle tells us in his Poetics that every tragic hero is supposed to have one of these, and that the hamartia is the thing that causes the hero's downfall. Aristotle also cites Oedipus as the best example ever of a tragic hero.

Why then is it so unclear to generation after generation, just what Oedipus's hamartia is? Let's take a stroll though some of the major theories and see what there is to see.

Theory # 1: Determination

It's true that if Oedipus wasn't so determined to find out the identity of Laius's real killer he would never have discovered the terrible truth of his life. Can you really call this a flaw, though? Before you go all Judge Judy on the guy, there’s another way to think about this. Oedipus is really exemplifying a prized and admirable human trait: determination. Why is it that we praise Hemingway’s

Old Man and H omer’s

Odysseus for the same determination for which we condemn Oedipus?

Furthermore, the reason Oedipus is dead set on solving the mystery is to save his people. Creon brings him word from the Oracle of Delphi that he must banish the murderer from the city or the plague that is ravaging Thebes will continue. It seems like

Oedipus is doing exactly what a good ruler ought to do. He's trying to act in the best interest of his people.

Theory #2: Anger

OK it's definitely true that our buddy Oedipus has a temper. Indeed it was rash anger that led to him unknowingly kill his real father, King Laius, at the crossroads. The killing of his father is an essential link in Oedipus's downfall, making his violent temper a good candidate for a tragic flaw.

Of course, Oedipus has a pretty good case for self defense. There he was

– a lone traveler, minding his own business. Then, out of nowhere, a bunch of guys show up, shove him off the road, and hit him in the head with whip. If we were Oedipus, we'd be angry too.

Killing all but one of them seems like an overreaction to modern audiences, but

Oedipus's actions wouldn't have seemed as radical to an ancient Greek audience. They lived in violent times. A man had the right to defend himself when attacked, especially when alone on a deserted road.

Within the play we see Oedipus's anger when he lashes out at both Creon and

Teiresias for bringing him bad news. This time he just talks trash, though. We don't see any ninja-style violence. What's most important to notice is that these angry tirades don't do the most important thing for a hamartia to do – they don't bring on Oedipus's downfall. He just rants for a while and threatens to do bad things but never does. These tirades don't cause anything else to happen. In fact they seem like a pretty natural reaction, to a whole lot of very bad news. Notice too, that anger in no way causes

Oedipus to sleep with Jocasta, which is an important part of his downfall.

Theory #3: Hubris

Hubris is translated as excessive pride. This term inevitably comes up almost every time you talk about a piece of ancient Greek literature. There's no denying that Oedipus is a proud man. Of course, he's got pretty good reason to be. He's the one that saved

Thebes from the Sphinx. If he hadn't come along and solved the Sphinx's riddle, the city would still be in the thrall of the creature. It seems that Oedipus rightly deserves the throne of Thebes.

Many scholars point out that Oedipus's greatest act of hubris is when he tries to deny his fate. The Oracle of Delphi told him long ago that he was destined to kill his father and sleep with his mother. Oedipus tried to escape his fate by never returning to

Corinth, the city where he grew up, and never seeing the people he thought were his parents again. Ironically, it was this action that led him to kill his real father Laius and to marry his mother Jocasta.

It's undeniable that by trying to avoid his fate Oedipus ended up doing the thing he most feared. This is probably the most popular theory as to Oedipus's hamartia . We would ask a rather simple question, though: what else was Oedipus supposed to do? Should he have just thrown up his hands and been like, "Oh well, if that's my fate, we should just get this over with." This thought is ridiculous and more than a little twisted. It hardly

seems like the moral we're supposed to take from the story. Is it really a flaw to try to avoid committing such horrendous acts?

Theory #4: We've got hamartia all wrong

Though hamartia is often defined as a tragic flaw, it actually has a much broader meaning. It's more accurately translated as an error in judgment or a mistake. You can still call it hamartia even if the hero makes these mistakes in a state of ignorance. The hero doesn't necessarily have to be intentionally committing the so-called "sin." Hmm, does that sound like anybody we know?

The word hamartia comes from the Greek hamartanein , which means "missing the mark." The hero aims his arrow at the bull's eye, but ends up hitting something altogether unexpected. Oedipus is the perfect example of this. The target for Oedipus is finding Laius's murderer in order to save Thebes. He does achieve this, but unfortunately brings disaster on himself in the process. Oedipus aim's for the bull's eye but ends up hitting his own eyes instead.

Sure, Oedipus has some flaws. Just like the rest of us, he's far from perfect. There's a strong argument, though, that ultimately the man is blameless. Some say that all this talk or tragic flaws was later scholars trying to impress a Christian worldview onto a pagan literature. The Greeks just didn't have quite the same ideas of sin that later societies developed.

The reason that Aristotle admired Oedipus the King so much is that the protagonist's downfall is caused by his own actions. We are moved to fear and pity at the end of the play not because Oedipus is sinful, but because he's always tried to do the right thing.

The terrible irony is that his desire to do the right thing that brings about his destruction.

When Oedipus gouges out his eyes at the end of the play, he symbolically becomes the thing he's always been: blind to the unknowable complexity of the universe.

If you want to learn more about Oedipus, check out the next play in this trilogy: Oedipus at Colonus .

Oedipus Timeline and Summary

Oedipus emerges from his palace at Thebes to see what’s up. He’s aware that the city is under a curse.

Oedipus talks to a priest, tells him not to worry, and lets him know that Creon,

Oedipus’s brother-in-law, is off seeking the advice of Apollo.

Creon returns and Oedipus learns that in order to rid the city of the curse, the murderer of the former King, Laius, must be discovered and expelled from

Thebes.

Oedipus promises to save the city.

Oedipus curses the murderer and demands information from anyone who knows about the crime.

Oedipus informs the Chorus that he’s called Teiresias for advice.

Oedipus briefly explains the city’s situation as well as Apollo’s advice. He asks

Teiresias for help.

Oedipus is enraged by Teiresias's reluctance to talk and demands that he speak whether he likes it or not.

Teiresias informs Oedipus that it was he (Oedipus) who killed Laius.

Oedipus, now even more enraged, accuses Creon and Teiresias of framing him in order to seize the throne.

Oedipus threatens Creon with death.

Oedipus talks to his wife Jocasta about what’s going on after Creon leaves.

Jocasta tells Oedipus prophecies are bogus, citing a prophecy that Laius would be murdered by his own son. In retrospect, that was a poor example.

Oedipus, worried he might have murdered Laius, promptly freaks out.

Oedipus summons and questions a servant who escaped murder at the crossroads where Laius was killed.

Oedipus tells Jocasta that as a child, a man once told him that his supposed mother and father (King and Queen of Corinth) were not his real parents. It was also prophesized that he would kill his father and sleep with his mother.

At this point, Jocasta has revealed that her son was prophesized to kill his father.

Oedipus has revealed that he was prophesized to kill his father. And no one finds this remotely suspicious. Perhaps it was a common prophecy back then.

Oedipus also reveals that he killed several men in a small incident at a crossroads. He hopes to find out from the servant whether Laius’s murderers were many or just one man. If it was a sole murderer, that will confirm his guilt.

Oedipus learns from a messenger that his father has just died of natural causes.

Oedipus concludes he could not have killed his father but is still worried about sleeping with his mother.

The messenger tells Oedipus that the King of Corinth and his wife, Merope, were not Oedipus’s real parents. Unable to have a child themselves, they adopted

Oedipus.

Oedipus was discovered with his feet pierced and tied by a shepherd who then gave the wounded infant to the messenger. Oedipus learns the man who originally found him is still living.

Oedipus ignores Jocasta’s suggestion that he drop the issue. He’s confused when she runs off screaming.

Oedipus questions the old shepherd who found him. With lots of threatening, he gets some information.

Finally, Oedipus pieces things together and realizes that Jocasta is his mother.

As predicted by the prophecy, he has slept with his mother and killed his father.

Oedipus finds Jocasta dead. In despair, he gouges his eyes out.

Oedipus pleads with Creon to watch over his daughters after he is exiled from

Thebes.

Creon

Character Analysis

Creon is portrayed as a pretty stand-up guy. He shows himself to be honest, forthright, and even tempered. The best example of Creon's reasonable nature happens when

Oedipus accuses him of conspiracy. Instead of getting all mad and talking junk to his paranoid brother-in-law (and nephew), Creon offers a rational explanation as to why he has no desire for Oedipus's crown.

For one, Creon already has all the power he wants. Because he is the brother of

Oedipus's wife, he basically has the same amount of status as Oedipus. Everybody sucks up to him to try and get to the king. If Creon had the crown he would have basically the same amount of power but ten times the headache. Who would want that?

In this scene, Creon’s rationality stands out in stark contrast to Oedipus's angry paranoia.

Creon's argument is also strengthened by the fact that he's the one who gave Oedipus the crown in the first place. After the death of Laius, Creon was the King of Thebes.

When the Sphinx started tormenting his city, he proclaimed that anybody who could solve her riddle could have his crown and the hand of his sister, Jocasta. Oedipus solved the riddle, and Creon proved to be a man of his word. A person who was truly power hungry would've gone back on his promise.

In the last scene of Oedipus the King , Creon also shows himself to be quite forgiving.

Rather than mocking Oedipus, who has just accused him of some pretty terrible things,

Creon is gentle. He brings the mutilated and grieving Oedipus inside, away from the public eye and also promises to care for the fallen king's children. In the end, it is only at

Oedipus's request that Creon banishes him from Thebes.

Creon doesn't come out quite so well in Oedipus at Colonus and nowhere near as good in Antigone . To learn more, check out these next two plays in the trilogy.

Creon Timeline and Summary

Creon asks for Apollo’s advice about the curse on Thebes.

Creon reports to Oedipus and the Chorus that the curse will be lifted when

Laius’s murderer is found and exiled from Thebes.

After meeting with Teiresias, Oedipus accuses Creon of framing Oedipus in order to seize the throne. Creon insists he has no intentions whatsoever of stealing the throne.

After learning that Oedipus is Laius's murderer, Creon quickly exiles him.

Teiresias

Character Analysis

Teiresias is kind of a cranky old fellow. We can see why. Though he's blind, he can see better than any of those around him. He's in tune with the mind of Apollo and receives visions of the future. Teiresias is also gifted in the magic art of augury, or telling the future from the behavior of birds. You might think these are pretty awesome skills, but it's probably difficult when everybody around you is doomed to shame, death, or mutilation. Not to mention, it must be annoying that whenever Teiresias does drop a little knowledge, people don't believe him. Both Jocasta and Oedipus are skeptical of his prophecies. Oedipus even goes so far as to accuse Teiresias of treason.

The blind seer only shows up for one scene in Oedipus the King , but it really packs a punch. Indeed it's the first real scene where we see any conflict, and as such, is necessary for keeping the audience interested in the play. In this scene, Oedipus gets angry at Teiresias because the prophet won't reveal the identity of Laius's murderer. It's clever of Sophocles to use this scene to show Oedipus's temper. Up until now the king has behaved rationally. He allows the Chorus to speak their mind and is doing his best to save his people. If we didn't see his anger here and later with Creon, we might not believe that Oedipus is capable of the multiple murders at the crossroads.

Probably the most interesting thing about this interchange is Teiresias's attitude towards the art of prophecy. Oedipus has good reason to be angry at him. King Oedipus has in front of him a man with the knowledge needed to save Thebes, but Teiresias won't reveal the necessary information. Instead he tells Oedipus that there's no point in revealing the truth, because everything that's going to happen is just going to happen anyway. Really? So, what is the point of prophets?

Teiresias's ironic attitude, toward revealing prophecy makes him symbolic of the whole conundrum of the play. Is Oedipus responsible for his actions? Yes, Oedipus causes his own downfall, but if he was doomed by the gods from the beginning, is it really his fault?

This debate didn't stop with the Greeks – it manifested itself once again in Christian thought, but was defined in terms of predestination vs. free will. Is our fate decided from birth or do we have a choice? This unanswerable question will most likely bug us humans till the end of our days.

Can't get enough Teiresias? Then check out Sophocles's Antigone .

Teiresias Timeline and Summary

Oedipus summons Teiresias and urges him to speak about Laius’s murder and

Oedipus’s identity.

Teiresias resists being questioned, but ultimately concedes.

Teiresias informs Oedipus that he murdered Laius, his father, and that he is married to his mother.

Oedipus accuses Teiresias of power seeking, and insults and dismissed him.

Jocasta

Character Analysis

Jocasta is the Queen of Thebes, but it's just not as glamorous as it sounds. By all accounts, it seems like her first marriage with King Laius was a happy one. That is, until he received the prophecy that he was destined to be murdered by his own son. This, of course, is what caused Jocasta and Laius to pierce and bind their one and only child's ankles and send him off to a mountainside to die. (In Ancient Greece, it was common to abandon unwanted children rather than kill them. That way the child's fate was in the hands of the gods, and the parent wasn't considered directly responsible for its death.)

Sometimes Jocasta is criticized for her distrust of prophecies. It's an understandable prejudice, though. Jocasta doesn't know that the prophecy Laius received came true – she believes her son to be dead and her husband to have been murdered by a band of thieves. This seemingly disproves the prophecy that said Laius would die by his son's hand. As far as Jocasta knows, she abandoned her baby boy to exposure, starvation, and wild beasts for nothing. She has very good reason to be more than a little skeptical of prophets.

It's important to note that though Jocasta is critical of prophecy, she isn't necessarily sacrilegious. In fact, within the play we see her praying to the god Apollo, making offerings, and asking for his protection. No other character, besides the Chorus, goes as far. In a way you could see her as one of the more pious characters onstage. (Not that it does her any good.) It seems that it isn't the gods themselves that Jocasta is skeptical of, but instead their supposed servants – men like Teiresias.

Jocasta realizes before Oedipus that he is her son, and that they have committed incest. When she hangs herself with bed sheets, it is symbolic of her despair over her incestuous actions. Interestingly, Jocasta plays both a spousal and maternal role to

Oedipus. She loves Oedipus romantically, but like a parent, she wishes to protect

Oedipus's innocence from the knowledge of their relationship.

Like Oedipus, Jocasta commits most of her "sins" in ignorance. Yes, she did abandon

Oedipus purposely when he was a baby, but even Oedipus says he wishes he had died on that mountainside.

Jocasta Timeline and Summary

Jocasta walks in on Creon and Oedipus arguing and tells them to cut it out.

Jocasta assures Oedipus that prophecies are consistently false and cites the example that her first husband, Laius, was prophesized to be killed by his own son, but that his son was killed as a baby.

Oedipus and Jocasta are somewhat relieved to find out from a messenger that

Oedipus’s father has just died of natural causes, which means Oedipus couldn’t have killed him.

Oedipus, however, is still worried about the sleeping with his mother part of the prophecy. Joc asta tells Oedipus he’s better off not thinking and worrying about it.

The messenger informs Oedipus and Jocasta that the King of Corinth and his wife were not Oedipus’s real parents. Oedipus was discovered with his feet pierced and tied by a shepherd who then gave him to the messenger.

Although she has no lines here, Jocasta presumably gets really nervous at this part.

Oedipus learns that the shepherd who originally found him is still living. He summons him. Realizing that she is Oedipus’s mother as well as lover, Jocasta suggests that Oedipus drop the issue before he discovers more than he bargained for.

Jocasta makes reference to seeing Oedipus for the last time and runs off in total grief. Oedipus assumes she’s ashamed of his low birth and vows to set things right.

Jocasta hangs herself.

The Chorus

Character Analysis

The Chorus is roughly like the peanutgallery (it’s even occasionally told to shut up).

Sophocles uses this group of Thebans to comment on the play's action and to foreshadow future events. He also uses it to comment on the larger impact of the characters' actions and to expound upon the play's central themes. In Oedipus the King we get choral odes on everything from tyranny to the dangers of blasphemy.

Sophocles also uses the Chorus at the beginning of the play to help tell the audience the given circumstances of the play. We hear all about the terrible havoc that the plague is wreaking on Thebes. By describing the devastation in such gruesome detail,

Sophocles raises the stakes for his protagonist, Oedipus. The people of Thebes are in serious trouble; Oedipus has to figure out who killed Laius fast, or he won't have any subjects left to rule.

Unlike his contemporary Euripides, Sophocles was known to integrate his choruses into the action of the play. In Oedipus the King we see the Chorus constantly advising

Oedipus to keep his cool. Most of the time in ancient tragedies choruses do a lot of lamenting of terrible events, but do little to stop them. Amazingly, though, the Chorus in

Oedipus the King manages to convince Oedipus not to banish or execute Creon. Just imagine how much worse Oedipus would have felt if he'd killed his uncle/brother-in-law on top of his other atrocities.

The Chorus in Oedipus the King goes through a distinct character arc. They begin by being supportive of Oedipus, believing, based on his past successes, that he's the right man to fix their woes. As Oedipus's behavior becomes more erratic, they become uncertain and question his motives. The fact Oedipus doesn't start lopping off heads at this point is pretty good evidence that he's not a tyrant. In the end, the Chorus is on

Oedipus's side again and laments his horrific fate.

Like most all ancient Greek tragedians, Sophocles divides his choral odes into strophe and antistrophe. Both sections had the same number of lines and metrical pattern. In

Greek, strophe means "turn," and antistrophe means "turn back." This makes sense when you consider the fact that, during the strophe choruses danced from right to left and during the antistrophe they did the opposite. Sophocles may have split them into

two groups, so that it was as if one part of the Chorus was conversing with the other.

Perhaps the dualities created by strophe and antistrophe, represent the endless, irresolvable debates for which Greek tragedy is famous.

The Chorus Timeline and Summary

Note: Although they pipe up only once in a while, the Chorus is present throughout the play as an observer.

At the start of Oedipus the King , the Chorus, using the Strophe-Antistrophe dichotomy, recounts the multiple problems the city faces under the curse including infertility, plague, and famine. They beg for help.

The Chorus informs Oedipus that they know nothing and suggests that Oedipus ask the blind prophet Teiresias for his knowledge.

The Chorus tells Oedipus and Creon to stop arguing.

After Oedipus and Creon leave, the Chorus talks about their fight.

Jocasta and the Chorus urge Oedipus to listen to Creon when he says he did not frame Oedipus for the murder of Laius.

The Chorus pleads with the Gods for mercy as Oedipus’s identity unfolds.

After Oedipus pieces things together and realizes what he’s done, the Chorus laments the tragedy.

Oedipus asks the Chorus to help send him out of Thebes or kill him.

For analysis: http://www.shmoop.com/oedipus-the-king/literary-devices.html

http://www.cliffsnotes.com/study_guide/literature/oedipus-trilogy/playsummary/oedipus-king.html

The Oedipus Trilogy By Sophocles About the Oedipus Trilogy

Historical Background

The Athens Sophocles knew was a small place

— a polis , one of the self-governing citystates on the Greek peninsula — but it held within it the emerging life of democracy, philosophy, and theater. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle wrote and taught in Athens, and their ideas gave birth to Western philosophy. Here, too, democracy took root and flourished, with a government ruled entirely by and for its citizens.

During the fifth century B.C., Athens presided as the richest and most advanced of all the city-states. Its army and navy dominated the Aegean after the defeat of the

Persians, and the tribute money offered to the conquering Athenians built the Acropolis, site of the Parthenon, as well as the public buildings that housed and glorified Athenian democracy. The wealth of Athens also assured regular public art and entertainment, most notably the Festival of Dionysus, where Sophocles produced his tragedies.

In the fifth century, Athens had reached the height of its development, but Athenians were vulnerable, too. Their land, like most of Greece, was rocky and dry, yielding little food. Athenians often fought neighboring city-states for farmland or cattle. They sought to solve their agricultural problems by reaching outward to more fertile lands through their conquering army and navy forces. Military skill and luck kept Athens wealthy for a time, but the rival city-state Sparta pressed for dominance during the long

Peloponnesian War (431- 404 B.C.). By the end of the fifth century, Sparta had starved

Athens into submission, and the power of the great city-state ended.

Greek Theater and Its Development

Sophocles' Oedipus Trilogy forms part of a theater tradition that encompasses much more than just entertainment. In fifth century B.C., Athens theater represented an essential public experience — at once social, political, and religious.

For Athenians, theater served as an expression of public unity. Ancient Greek myth

— the theme of most tragedies

— not only touched members of the audience individually, but drew them together as well. The dramatization of stories from a shared heritage helped to nurture and preserve a cultural identity through times of hardship and war.

But beyond its social and political importance, Greek drama also held a religious significance that made it a sacred art. Originally, the Greek theater tradition emerged from a long history of choral performance in celebration of the god Dionysus.

The Festival of Dionysus — whose high point was a dramatic competition — served as a ritual to honor the god of wine and fertility and to ask his blessing on the land. To attend the theater, then, was a religious duty and the responsibility of all pious citizens.

Drama began, the Greeks say, when the writer and producer Thespis separated one man from the chorus and gave him some lines to speak by himself. In 534 B.C., records show that this same Thespis produced the first tragedy at the Festival of Dionysus.

From then on, plays with actors and a chorus formed the basis of Greek dramatic performances.

The actual theater itself was simple, yet imposing. Actors performed in the open air, while the audience — perhaps 15,000 people — sat in seats built in rows on the side of a hill. The stage was a bare floor with a wooden building (called the skene ) behind it.

The front of the skene might be painted to suggest the location of the action, but its most practical purpose was to offer a place where actors could make their entrances and exits.

In Greek theater, the actors were all male, playing both men and women in long robes with masks that depicted their characters. Their acting was stylized, with wide gestures and movements to represent emotion or reaction. The most important quality for an actor was a strong, expressive voice because chanted poetry remained the focus of dramatic art.

The simplicity of production emphasized what Greeks valued most about drama — poetic language, music, and evocative movement by the actors and chorus in telling the story. Within this simple framework, dramatists found many opportunities for innovation and embellishment. Aeschylus, for example, introduced two actors, and used the chorus to reflect emotions and to serve as a bridge between the audience and the story.

Later, Sophocles introduced painted scenery, an addition that brought a touch of realism to the bare Greek stage. He also changed the music for the chorus, whose size swelled from twelve to fifteen members. Most important, perhaps, Sophocles increased the number of actors from two to three

— a change that greatly increased the possibility for interaction and conflict between characters on stage.

The Oedipus Myth

Like other dramatists of his time, Sophocles wrote his plays as theatrical interpretations of the well-known myths of Greek culture — an imaginative national history that grew through centuries. Sophocles and his contemporaries particularly celebrated the mythic heroes of the Trojan War, characters who appear in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey .

The myth of Oedipus

— which also appears briefly in Homer — represents the story of a man's doomed attempt to outwit fate. Sophocles' tragedy dramatizes Oedipus' painful discovery of his true identity, and the despairing violence the truth unleashes in him.

Warned by the oracle at Delphi that their son will kill his father, King Laius and Queen

Jocasta of Thebes try to prevent this tragic destiny. Laius pierces his son's feet and gives him to a shepherd with instructions to leave the baby in the mountains to die. But pitying the child, the shepherd gives him to a herdsman, who takes the baby far from

Thebes to Corinth. There, the herdsman presents the child to his own king and queen, who are childless. Without knowing the baby's identity, the royal couple adopt the child and name him Oedipus ("swollen-foot").

Oedipus grows up as a prince of Corinth, but hears troubling stories that the king is not his real father. When he travels to Delphi to consult the oracle, Oedipus learns the prophecy of his fate, that he will kill his father and marry his mother. Horrified, he determines to avoid his terrible destiny by never returning home.

Near Thebes, Oedipus encounters an old man in a chariot with his attendants. When the old man insults and strikes him in anger, Oedipus kills the man and his servants.

The old man, of course, is Oedipus' father, Laius, but Oedipus does not realize this.

Outside Thebes, Oedipus meets the monstrous Sphinx, who has been terrorizing the countryside. The Sphinx challenges Oedipus with her riddle: "What goes on four feet at dawn, two at noon, and three at evening?" Oedipus responds with the right answer ("A man") and kills the monster.

The Theban people proclaim him a hero, and when they learn that Laius has been killed, apparently by a band of robbers, they accept Oedipus as their king. Oedipus marries Jocasta, and they have four children. Thus, despite all his efforts to prevent it,

Oedipus fulfills the dreadful prophecy.

Dramatic Irony

Since everyone knew the myth, Sophocles' play contained no plot surprises for his audience. Instead, the tragedy held their interest through new interpretation, poetic language, and, most especially, dramatic irony.

Dramatic irony arises from the difference between what an audience knows and what the characters on stage know. In Oedipus the King , for example, everyone in the audience knows from the beginning that Oedipus has killed his father and married his mother. The tension of the play, then, develops from Oedipus' slow but inevitable progress toward this terrible self-knowledge.

Watching Oedipus' fate unfold, the audience identifies with the hero, sharing vicariously in the horror of the reversal he suffers and acknowledging the power of destiny. By connecting with the audience, Sophocles has achieved the catharsis that Aristotle thought was so important. In accomplishing this dramatic feat, Aristotle declares,

Sophocles' Oedipus the King stands as the greatest tragedy ever written.

The Oedipus Trilogy By Sophocles Character List

Oedipus the King

Oedipus King of Thebes. As a young man, he saved the city of Thebes by solving the riddle of the Sphinx and destroying the monster. He now sets about finding the murderer of the former king Laius to save Thebes from plague.

Creon The second-in-command in Thebes, brother-in-law of Oedipus. He is Oedipus' trusted advisor, selected to go to the oracle at Delphi to seek the Apollo's advice in saving the city from plague.

Tiresias A blind prophet who has guided the kings of Thebes with his advice and counsel.

Jocasta Queen of Thebes, wife of Oedipus. She was the widow of Thebes' former king,

Laius, and married Oedipus when he saved the city from the Sphinx.

A Messenger from Corinth A man bringing news of the royal family to Oedipus.

A Shepherd A herder from the nearby mountains, who once served in the house of

Laius.

A Messenger A man who comes from the palace to announce the death of the queen and the blinding of Oedipus.

Antigone and Ismene Oedipus' young daughters.

Chorus A group of Theban elders, and their Leader, who comment on the events of the drama and react to its tragic progression.

Oedipus at Colonus

Oedipus Former king of Thebes, now a blind beggar who wanders from place to place.

Considered a pariah because of his sins, Oedipus suffers abuse and rejection everywhere he goes.

Antigone Daughter of Oedipus. She leads her blind father on his travels and serves his needs.

A Citizen of Colonus A passer-by who notices Oedipus and Antigone trespassing on sacred ground.

Ismene Daughter of Oedipus, sister of Antigone. She lives in Thebes and brings her father and sister news while they stay in Colonus.

Theseus King of Athens. He acts as Oedipus' ally by protecting him in Colonus and witnesses his death.

Creon King of Thebes, brother-in-law of Oedipus. Responsible for Oedipus' exile, Creon is now interested in returning the former king to Thebes to avoid a curse.

Polynices Son of Oedipus, brother of Antigone and Ismene. Driven out of Thebes after a power struggle with his brother Eteocles and Creon, he is an exile like his father, and plans to take Thebes by force.

A Messenger A man who tells the elders of the city of Oedipus' death.

Chorus A group of elders of Colonus who confront Oedipus and comment on the unfolding events in the play.

Antigone

Antigone Daughter of Oedipus. She defies a civil law forbidding the burial of Polynices, her brother, in order to uphold the divine law requiring that the dead be put to rest with proper rituals.

Ismene Sister of Antigone, daughter of Oedipus. She timidly refuses to join her sister in disobeying the civil law, but later wants to join her in death.

Creon King of Thebes, brother-in-law of Oedipus, uncle of Polynices, Antigone, and

Ismene. His strict order to leave Polynices' body unburied and his refusal to admit the possibility that he is wrong bring about the events of the tragedy.

Haemon Son of Creon, promised in marriage to Antigone. He argues calmly for

Antigone's release, but meets with angry rejection.

A Sentry Who brings news of the attempted burial of Polynices.

Tiresias The blind prophet who advised Laius and Oedipus, before Creon. His auguries show that the gods are angered by Creon's decision to leave Polynices unburied.

Eurydice Queen of Thebes, wife of Creon. On hearing of the death of her son, she kills herself.

A Messenger A man who tells of the deaths of Antigone, Haemon, and Eurydice.

Chorus The elders of Thebes and their Leader. They listen loyally to Creon and rebuke

Antigone, but advise the king to change his mind when Tiresias warns of the gods' punishment.

The Oedipus Trilogy By Sophocles Play Summary Oedipus the King

Oedipus the King unfolds as a murder mystery, a political thriller, and a psychological whodunit. Throughout this mythic story of patricide and incest, Sophocles emphasizes the irony of a man determined to track down, expose, and punish an assassin, who turns out to be himself.

As the play opens, the citizens of Thebes beg their king, Oedipus, to lift the plague that threatens to destroy the city. Oedipus has already sent his brother-in-law, Creon, to the oracle to learn what to do.

On his return, Creon announces that the oracle instructs them to find the murderer of

Laius, the king who ruled Thebes before Oedipus. The discovery and punishment of the murderer will end the plague. At once, Oedipus sets about to solve the murder.

Summoned by the king, the blind prophet Tiresias at first refuses to speak, but finally accuses Oedipus himself of killing Laius. Oedipus mocks and rejects the prophet angrily, ordering him to leave, but not before Tiresias hints darkly of an incestuous marriage and a future of blindness, infamy, and wandering.

Oedipus attempts to gain advice from Jocasta, the queen; she encourages him to ignore prophecies, explaining that a prophet once told her that Laius, her husband, would die at the hands of their son. According to Jocasta, the prophecy did not come true because the baby died, abandoned, and Laius himself was killed by a band of robbers at a crossroads.

Oedipus becomes distressed by Jocasta's remarks because just before he came to

Thebes he killed a man who resembled Laius at a crossroads. To learn the truth,

Oedipus sends for the only living witness to the murder, a shepherd.

Another worry haunts Oedipus. As a young man, he learned from an oracle that he was fated to kill his father and marry his mother. Fear of the prophecy drove him from his home in Corinth and brought him ultimately to Thebes. Again, Jocasta advises him not to worry about prophecies.

Oedipus finds out from a messenger that Polybus, king of Corinth, Oedipus' father, has died of old age. Jocasta rejoices

— surely this is proof that the prophecy Oedipus heard is worthless. Still, Oedipus worries about fulfilling the prophecy with his mother, Merope, a concern Jocasta dismisses.

Overhearing, the messenger offers what he believes will be cheering news. Polybus and Merope are not Oedipus' real parents. In fact, the messenger himself gave Oedipus to the royal couple when a shepherd offered him an abandoned baby from the house of

Laius.

Oedipus becomes determined to track down the shepherd and learn the truth of his birth. Suddenly terrified, Jocasta begs him to stop, and then runs off to the palace, wild with grief.

Confident that the worst he can hear is a tale of his lowly birth, Oedipus eagerly awaits the shepherd. At first the shepherd refuses to speak, but under threat of death he tells what he knows

— Oedipus is actually the son of Laius and Jocasta.

And so, despite his precautions, the prophecy that Oedipus dreaded has actually come true. Realizing that he has killed his father and married his mother, Oedipus is agonized by his fate.

Rushing into the palace, Oedipus finds that the queen has killed herself. Tortured, frenzied, Oedipus takes the pins from her gown and rakes out his eyes, so that he can no longer look upon the misery he has caused. Now blinded and disgraced, Oedipus begs Creon to kill him, but as the play concludes, he quietly submits to Creon's leadership, and humbly awaits the oracle that will determine whether he will stay in

Thebes or be cast out forever.

The Oedipus Trilogy By Sophocles Play Summary Oedipus at Colonus

In Oedipus at Colonus , Sophocles dramatizes the end of the tragic hero's life and his mythic significance for Athens. During the course of the play, Oedipus undergoes a transformation from an abject beggar, banished from his city because of his sins, into a figure of immense power, capable of extending (or withholding) divine blessings.

As the play opens, Oedipus appears as a blind beggar, banished from Thebes. Oedipus and Antigone, his daughter and guide, learn they have reached Colonus, a city near

Athens, and are standing on ground sacred to the Eumenides (another name for the

Furies). This discovery causes Oedipus to demand that Theseus, king of Athens, be brought to him. Meanwhile, Oedipus' other daughter, Ismene, arrives from Thebes with the news that Creon and Eteocles, Oedipus' son, want Oedipus to return to Thebes in order to secure his blessing and avoid a harsh fate foretold by the oracle. Oedipus refuses to return, and when Theseus arrives, Oedipus promises him a great blessing for the city if he is allowed to stay, die, and be buried at Colonus.

Theseus pledges his help, and when Creon appears threatening war and holding the daughters hostage for Oedipus' return, the Athenian king drives Creon off and frees the daughters. Shortly after Creon leaves, Oedipus' other son, Polynices, arrives to beg his father's support in his war to regain the Theban throne from his brother and Creon.

Oedipus angrily curses Polynices, prophesying that he and his brother Eteocles will die at one another's hand.

Suddenly, Oedipus hears thunder and declares that his death is at hand. He leads

Theseus, Ismene, and Antigone into a hidden part of the grove and ritually prepares for death. Only Theseus, however, actually witnesses the end of Oedipus' life.

Since Oedipus' final resting place is at Colonus, Athens receives his blessing and protection, and Thebes earns his curse. At the conclusion of the play, Antigone and

Ismene return to Thebes, hoping to avert the war and civil strife.

The Oedipus Trilogy By Sophocles Play Summary Antigone

After the bloody siege of Thebes by Polynices and his allies, the city stands unconquered. Polynices and his brother Eteocles, however, are both dead, killed by each other, according to the curse of Oedipus, their father.

Outside the city gates, Antigone tells Ismene that Creon has ordered that Eteocles, who died defending the city, is to be buried with full honors, while the body of Polynices, the invader, is left to rot. Furthermore, Creon has declared that anyone attempting to bury

Polynices shall be publicly stoned to death. Outraged, Antigone reveals to Ismene a plan to bury Polynices in secret, despite Creon's order. When Ismene timidly refuses to defy the king, Antigone angrily rejects her and goes off alone to bury her brother.

Creon discovers that someone has attempted to offer a ritual burial to Polynices and demands that the guilty one be found and brought before him. When he discovers that

Antigone, his niece, has defied his order, Creon is furious. Antigone makes an impassioned argument, declaring Creon's order to be against the laws of the gods themselves. Enraged by Antigone's refusal to submit to his authority, Creon declares that she and her sister will be put to death.

Haemon, Creon's son who was to marry Antigone, advises his father to reconsider his decision. The father and son argue, Haemon accusing Creon of arrogance, and Creon accusing Haemon of unmanly weakness in siding with a woman. Haemon leaves in anger, swearing never to return. Without admitting that Haemon may be right, Creon amends his pronouncement on the sisters: Ismene shall live, and Antigone will be sealed in a tomb to die of starvation, rather than stoned to death by the city.

The blind prophet Tiresias warns Creon that the gods disapprove of his leaving

Polynices unburied and will punish the king's impiety with the death of his own son.

After rejecting Tiresias angrily, Creon reconsiders and decides to bury Polynices and free Antigone.

But Creon's change of heart comes too late. Antigone has hanged herself and Haemon, in desperate agony, kills himself as well. On hearing the news of her son's death,

Eurydice, the queen, also kills herself, cursing Creon.

Alone, in despair, Creon accepts responsibility for all the tragedy and prays for a quick death. The play ends with a somber warning from the chorus that pride will be punished by the blows of fate.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oedipus_at_Colonus

Oedipus at Colonus

Oedipus at Colonus (also Oedipus Coloneus , Ancient Greek

: Ο ἰ δίπους ἐ π ὶ Κολων ῷ

,

Oidipous epi Kolōnō

) is one of the three Theban plays of the Athenian tragedian

Sophocles . It was written shortly before Sophocles' death in 406 BC and produced by his grandson (also called Sophocles) at the Festival of Dionysus in 401 BC .

In the timeline of the plays, the events of Oedipus at Colonus occur after Oedipus the

King and before Antigone ; however, it was chronologically the last of Sophocles' three

Theban plays to be written. The play describes the end of Oedipus ' tragic life. Legends differ as to the site of Oedipus' death; Sophocles set the place at Colonus , a village near

Athens and also Sophocles' own birthplace, where the blinded Oedipus has come with his daughters Antigone and Ismene as suppliants of the Erinyes and of Theseus , the king of Athens .

Plot

Oedipus at Colonus , Jean-Antoine-Théodore

Giroust , 1788, Dallas Museum of Art

Led by Antigone, Oedipus enters the village of

Colonus and sits down on a stone. They are approached by a villager, who demands that they leave, because that ground is sacred to the

Furies , or Erinyes . Oedipus recognizes this as a sign, for when he received the prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother, Apollo also revealed to him that at the end of his life he would die at a place sacred to the Furies, and be a blessing for the land in which he is buried.

The chorus of old men from the village enters, and persuades Oedipus to leave the holy ground. They then question him about his identity, and are horrified to learn that he is the son of Laius . Although they promised not to harm Oedipus, they wish to expel him from their city, fearing that he will curse it. Oedipus answers by explaining that he is not morally responsible for his crimes, since he killed his father in self-defence.

Furthermore, he asks to see their king, Theseus , saying, "I come as someone sacred, someone filled with piety and power, bearing a great gift for all your people."

[1]

The chorus is amazed, and decides to reserve their judgment of Oedipus until Theseus, king of Athens, arrives.

Ismene arrives on horse, rejoicing to see her father and sister. She brings the news that

Eteocles has seized the throne of Thebes from his elder brother, Polyneices , while

Polyneices is gathering support from the Argives to attack the city. Both sons have heard from an oracle that the outcome of the conflict will depend on where their father is buried. Ismene tells her father that it is Creon 's plan to come for him and bury him at the border of Thebes, without proper burial rites, so that the power which the oracle says his grave will have will not be granted to any other land. Hearing this, Oedipus curses both of his sons for not treating him well, contrasting them with his devoted daughters.

He pledges allegiance with neither of his feuding sons, but with the people of Colonus, who thus far have treated him well, and further asks them for protection from Creon.

Because Oedipus trespassed on the holy ground of the Euminides, the villagers tell him that he must perform certain rites to appease them. Ismene volunteers to go perform them for him and departs, while Antigone remains with Oedipus. Meanwhile, the chorus questions Oedipus once more, desiring to know the details of his incest and patricide.

After he relates his sorrowful story to them, Theseus enters, and in contrast to the prying chorus states, "I know all about you, son of Laius."

[2]

He sympathizes with

Oedipus, and offers him unconditional aid, causing Oedipus to praise Theseus and offer him the gift of his burial site, which will ensure victory in a future conflict with Thebes.

Theseus protests, saying that the two cities are friendly, and Oedipus responds with what is perhaps the most famous speech in the play. "Oh Theseus, dear friend, only the gods can never age, the gods can never die. All else in the world almighty Time obliterates, crushes all to nothing..."

[3]

Theseus makes Oedipus a citizen of Athens, and leaves the chorus to guard him as he departs. The chorus sings about the glory and beauty of Athens.

Creon, who is the representative of Thebes, comes to Oedipus and feigns pity for him and his children, telling him that he should return to Thebes. Oedipus is horrified, and recounts all of the harms Creon has inflicted on him. Creon becomes angry and reveals that he has already captured Ismene; he then instructs his guards to forcibly seize

Antigone. His men begin to carry them off toward Thebes, perhaps planning to use

them as blackmail to get Oedipus to follow, out of a desire to return Thebans to Thebes, or simply out of anger. The chorus attempts to stop him, but Creon threatens to use force to bring Oedipus back to Thebes. The chorus then calls for Theseus, who comes from sacrificing to Poseidon to condemn Creon, telling him, "You have come to a city that practices justice, that sanctions nothing without law."

[4]

Creon replies by condemning Oedipus, saying "I knew [your city] would never harbor a fatherkiller...worse, a creature so corrupt, exposed as the mate, the unholy husband of his own mother."

[5]

Oedipus, infuriated, declares once more that he is not morally responsible for what he did. Theseus leads Creon away to retake the two girls. The

Athenians overpower the Thebans and return both girls to Oedipus. Oedipus moves to kiss Theseus in gratitude, then draws back, acknowledging that he is still polluted.

Theseus then informs Oedipus that a suppliant has come to the temple of Poseidon and wishes to speak with him; it is Oedipus' son Polynices, who has been banished from

Thebes by his brother Eteocles . Oedipus does not want to talk to him, saying that he loathes the sound of his voice, but Antigone persuades him to listen, saying, "Many other men have rebellious children, quick tempers too...but they listen to reason, they relent."

[6]

Oedipus gives in to her, and Polynices enters, lamenting Oedipus' miserable condition and begging his father to speak to him. He tells Oedipus that he has been driven out of the Thebes unjustly by his brother, and that he is preparing to attack the city. He knows that this is the result of Oedipus' curse on his sons, and begs his father to relent, even going so far as to say "We share the same fate" to his father.

[7]

Oedipus tells him that he deserves his fate, for he cast his father out. He foretells that his two sons will kill each other in the coming battle. "Die! Die by your own blood brother's hand —die!—killing the very man who drove you out! So I curse your life out!" [8]

Antigone tries to restrain her brother, telling him that he should not attack Thebes and avoid dying at his brother's hand. Polyneices refuses to be dissuaded, and exits.

Following their conversation there is a fierce thunderstorm, which Oedipus interprets as a sign from Zeus of his impending death. Calling for Theseus, he tells him that it is time for him to give the gift he promised to Athens. Filled with strength, the blind Oedipus stands and walks, calling for his children and Theseus to follow him.

A messenger enters and tells the chorus that Oedipus is dead. He led his children and

Theseus away, then bathed himself and poured libations, while his daughters grieved.

He told them that their burden of caring for him was gone, and asked Theseus to swear

not to forsake his daughters. Then he sent his children away, for only Theseus could know the place of his death, and pass it on to his heir. When the messenger turned back to look at the spot where Oedipus last stood, he says that "We couldn't see the man- he was gone- nowhere! And the king, alone, shielding his eyes, both hands spread out against his face as if- some terrible wonder flashed before his eyes and he, he could not bear to look."

[9]

Theseus enters with Antigone and Ismene, who are weeping and mourning their father. Antigone longs to see her father's tomb, even to be buried there with him rather than live without him. The girls beg Theseus to take them, but he reminds them that the place is a secret, and that no one may go there. "And he said that if I kept my pledge, I'd keep my country free of harm forever."

[10]

Antigone agrees, and asks for passage back to Thebes, where she hopes to stop the Seven

Against Thebes from marching. Everyone exits toward Athens.

Analysis and themes

There is less action in this play than in Oedipus the King , and more philosophical discussion. Here, Oedipus discusses his fate as related by the oracle, and claims that he is not fully guilty because his crimes of murder and incest were committed in ignorance. Despite being blinded and exiled and facing violence from Creon and his sons, in the end Oedipus is accepted and absolved by Zeus.

Historical context

In the years between the play's composition and its first performance, Athens underwent many changes. Defeated by the Spartans , the city was placed under the rule of the

Thirty Tyrants , and the citizens who opposed their rule were exiled or executed.

[11]

This certainly affected the way that early audiences reacted to the play, just as the invasion of Athens and its diminished power surely affected Sophocles as he wrote it.

The play contrasts the cities of Athens and Thebes quite sharply. Thebes is often used in Athenian dramas as a city in which proper boundaries and identities are not maintained, allowing the playwright to explore themes like incest, murder, and hubris in a safe setting.

Fate

While the two other plays about Oedipus often bring up the theme of a person's moral responsibility for their destiny, and whether it is possible to rebel against destiny,

Oedipus at Colonus is the only one to address it explicitly. Oedipus vehemently states that he is not responsible for the actions he was fated to commit.

Guilt

‘Oedipus at Colonus’ suggests that, in breaking divine law, a ruler’s limited understanding may lead him to believe himself fully innocent; however, his lack of awareness does not change the objective fact of his guilt.

[12]

Nevertheless, determination of guilt is far more complex than this, as illustrated by the dichotomy between the blessing and the curse upon Oedipus. He has committed two crimes which render him a sort of monster and outcast among men: incest and patricide. His physical suffering, including his self-inflicted blindness, and lonely wandering, are his punishment. However, in death, he will be favored; the place in which he dies will be blessed. This suggests that willful action is in some part of guilt; the fact that Oedipus is “rationally innocent” – that he sinned unknowingly – decreases his guilt, allowing his earthly sufferings to serve as sufficient expiation for his sins.

[12]

Heroization of Oedipus

Darice Birge argues that Oedipus at Colonus is a story of Oedipus' heroization. It is a transition piece from the Oedipus of Oedipus Tyrannus whose acts were abominable to the Oedipus we see at the end of Oedipus at Colonus who is so powerful that he is sought after by two separate major cities. The major image used to show this transition from beggar to hero is Oedipus' relationship with the sacred grove of the Erinyes. At the beginning of the play, Oedipus has to be led through the grove by Antigone and is only allowed to go through it because as a holy place it is an asylum for beggars. He recognizes the grove as the location once described to him in a prophecy as his final resting place. When Elders come looking for him, Oedipus enters the grove. This act, according to Birge, is his first act as a hero. He has given up his habit of trying to fight divine will (as was his wont in Oedipus Tyrannus ) and now is no longer fighting prophecies, but is rather accepting this grove as the place of his death. Oedipus then hints at his supernatural power, an ability to bring success to those who accept him and suffering to those who turned him away. Oedipus' daughter Ismene then arrives, bringing news that Thebes, the city that once exiled Oedipus for his sins, wants him back for his hero status. Ismene furthers Oedipus' status as a hero when she performs a libation to the Erinyes, but his status is cemented when he chooses his final resting place as a hidden part of the sacred grove, which even his daughters can't know.