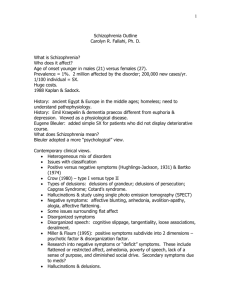

Psychogenesis Versus Biogenesis

advertisement