public health and primary care course handbook 2012

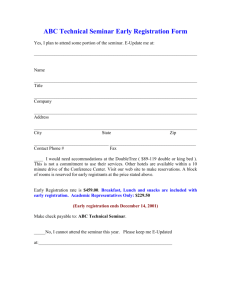

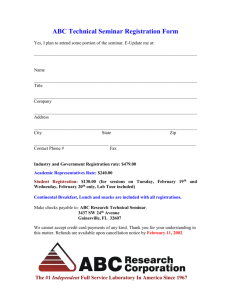

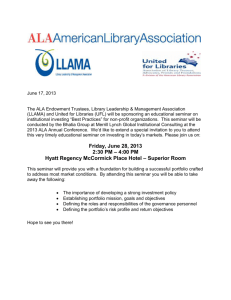

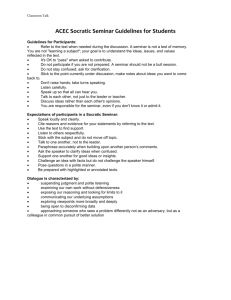

advertisement