UC Annual Accountability Report 2013

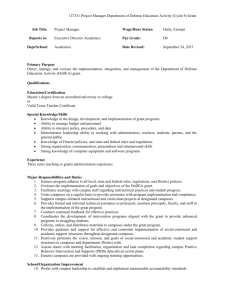

advertisement