Contents - Palgrave

advertisement

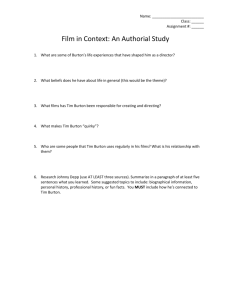

Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Contents List of Figures ix Mainstream Outsider: Burton Adapts Burton Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock 1 Part I Aesthetics 1 Burton Black Murray Pomerance 2 Costuming the Outsider in Tim Burton’s Cinema, or, Why a Corset Is like a Codfish Catherine Spooner 3 Danny Elfman’s Musical Fantasyland, or, Listening to a Snow Globe Isabella van Elferen 4 Tim Burton’s “Filled” Spaces: Alice in Wonderland J. P. Telotte 33 47 65 83 Part II Influences and Contexts 5 How to See Things Differently: Tim Burton’s Reimaginings Aaron Taylor 6 “He wants to be just like Vincent Price”: Influence and Intertext in the Gothic Films of Tim Burton Stephen Carver 7 Tim Burton’s Trash Cinema Roots: Ed Wood and Mars Attacks! Rob Latham 8 A Monstrous Childhood: Edward Gorey’s Influence on Tim Burton’s The Melancholy Death of Oyster Boy Eden Lee Lackner Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 99 117 133 151 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 viii ● Contents 9 It Came from Burbank: Exhibiting the Art of Tim Burton Cheryl Hicks 10 “Tim Is Very Personal”: Sketching a Portrait of Tim Burton’s Auteurist Fandom and Its Origins Matt Hills 165 179 Part III Thematics 11 Tim Burton’s Popularization of Perversity: Edward Scissorhands, Batman Returns, Sleepy Hollow, and Corpse Bride Carol Siegel 12 “This is my art, and it is dangerous!”: Tim Burton’s Artist-Heroes Dominic Lennard 13 Tim Burton and the Creative Trickster: A Case Study of Three Films Katherine A. Fowkes 217 Contributors 245 Index 249 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 197 231 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Mainstream Outsider: Burton Adapts Burton Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock T he original Frankenweenie (1984)—a 25-minute black-and-white reworking of James Whale’s 1931 version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) with nods to Whale’s 1935 sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein—was Tim Burton’s third professional directorial effort. It followed Vincent (1982), a six-minute black-and-white stop-motion film made while Burton was working at Disney, and a live-action version of the Grimms’ fairy tale Hansel and Gretel (1982) for the then embryonic cable Disney Channel.1 Championed by Burton’s advocate at Disney, Julie Hickson, Frankenweenie was financed by Disney at a cost just shy of $1 million and featured the voices of Shelley Duvall, Daniel Stern, and Paul Bartel. Intended to be shown with Pinocchio upon its re-release in 1984, the film was shelved by Disney after it received a PG rating. Parents shown the film as part of its two test screenings found the film too “intense” (Smith and Matthews 37) for children, and Smith and Matthews observe that the reason for Disney’s lack of support for this venture was similar to that offered for its lack of support for Vincent: the film’s approach to childhood and death was too dark. Almost 30 years later, a greatly expanded Frankenweenie—a full-length 3D stop-motion remake of the original (also rated PG)—was released in 2012, having been produced by Disney at a cost of approximately $39 million. Frankenweenie “2.0,” which features the voices of Burton mainstays Catherine O’Hara, Winona Ryder, and Martin Landau, placed fifth among films that opened the weekend of October 5, 2012, grossing $11.5 million and, as of late February 2013, had grossed over $35 million (IMDd). The 2012 Frankenweenie is an especially useful film to introduce this volume of essays on Tim Burton—surprisingly, the first of its kind—for two reasons: first, the film itself functions as a kind of textual Frankenstein’s monster, a cinematic pastiche assembled out of the bits and pieces not only of Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 2 ● Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock Burton’s cinematic career but of Hollywood horror more generally.2 To the viewer with the requisite Burton and Hollywood horror “literacies,” it quickly becomes clear that the expanded Frankenweenie engages in complex and persistent processes of citationality and adaptation as it derives its charge from its connections to other works—Mary Shelley’s canonical Gothic novel, Burton’s earlier works, and classic horror films. What Burton has done with the 2012 Frankenweenie is to take the original work from 1984, build onto it with pieces from his other films, and then shock it into life by connecting it to the whole history of cinematic horror. By focusing on Frankenweenie, one can in fact cast one’s glance broadly across the vista of Burton’s entire career. Second, the process of moving from the original 25-minute Frankenweenie of 1984, which Disney quashed because it was too dark, to the “reimagined” but equally dark full-length general release Frankenweenie of 2012 is emblematic of the ways in which Burton has taken his quirky aesthetic and seriocomic vision from Hollywood’s margins to its center—all while staunchly continuing to insist on his outsider status. Burton positions himself repeatedly as the rebellious outsider (an identification that, as Cheryl Hicks points out in her essay for this volume, becomes the narrative of his twenty-first-century art exhibition initiated by the New York Museum of Modern Art), while in fact now standing at the center of New Hollywood. This transformation of Burton into an oxymoronic “mainstream outsider” can be mapped by surveying the journey from Frankenweenie 1984 to Frankenweenie 2012. The Frankenstein’s Monster Frankenweenie, the story of a grieving young boy, Victor Frankenstein, who reanimates the corpse of his beloved dog Sparky, is obviously intended as a parody of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and, as such, gestures toward an entire history of Gothic literature and film that informs both Frankenweenie and Burton’s oeuvre more generally; however, the extended and reworked 2012 version of the film, in both its specific details and general themes, also functions as a highly condensed recapitulation of Burton’s entire career—if one were to consider Burton’s films as a sort of cinematic universe, Frankenweenie 2012 would be the black hole at its center, with the other films orbiting around it and being sucked in by its irresistible gravity at differing velocities. Accordingly, close attention to the film permits insight into the recurring motifs and preoccupations that have structured Burton’s body of cinematic work, and this in turn allows for speculation concerning his success. With this in mind, in this chapter I will first offer summaries of the original 1984 film and the 2012 remake and then, turning my attention to the latter, consider Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Mainstream Outsider: Burton Adapts Burton ● 3 the film as a pastiche of significant recurring Burton elements. Because one could write entire chapters on individual themes and devices in Burton (as indeed do the contributors to this collection), this survey, rather than being exhaustive, will focus on particularly resonate themes and images as it moves chronologically through the films Burton has directed (or, in the case of The Nightmare Before Christmas [1993], created). Intended to be more suggestive than complete, these commentaries will be developed in varying lengths. The original 1984 Frankenweenie is the story of Victor Frankenstein (voiced by Barret Oliver), who is himself a filmmaker who directs amateur productions starring his bull terrier Sparky. After Sparky is hit and killed by a car, Victor—having learned at school about the electrical stimulation of muscles—decides to reanimate Sparky by creating an elaborate apparatus to harness the power of lightening. He is successful, but his neighbors are terrified of the resurrected Sparky. After Sparky runs away, Victor follows him—now pursued by the de rigueur angry mob—to a miniature golf course, where they hide in a prop windmill. When the windmill is set on fire, Victor falls and is knocked out; Sparky comes to his rescue but is crushed by the windmill. The mob, then recalibrating its animosity, revivifies Sparky with jumper cables connected to a car battery and the renewed pup falls in love with a black poodle with a Bride of Frankenstein hairdo, complete with a shock of white fur. The 2012 reboot done as a 3D black-and-white stop-motion release uses this same general framework, but elaborates upon it greatly. In the updated version, the reanimation of Sparky by Victor (voiced by Charlie Tahan) is discovered by Victor’s hunchbacked classmate Edgar “E” Gore (Atticus Shaffer), who blackmails Victor into reviving a departed goldfish and then shares the news with other classmates who themselves seek to resurrect pets of their own. All the revivifications go terribly awry resulting in a Mad Monster Party-esque mélange of supernatural nasties, including a winged vampire cat, a were-rat, a mummified hamster, a giant Gamera-like turtle, and a squadron of Gremlinesque sea monkeys that terrorize the town of New Holland. The townsfolk turn on Sparky, blaming him for the chaos and chasing him to a windmill to which the winged vampire cat (Mr. Whiskers) has carried off Elsa van Helsing (Winona Ryder), the niece of the town’s mayor Mr. Burgemeister (Martin Short). The windmill is set ablaze and Victor and Sparky enter and rescue Elsa, but Victor is trapped inside. Sparky then rescues Victor, only to be dragged back inside by Mr. Whiskers and both pets are killed; as in the original, the town’s sentiment shifts and Sparky is reanimated once again (Figure i.1). Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 4 ● Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock Figure i.1 The reanimated Sparky Vincent (1982) It is perhaps not surprising that Frankenweenie, both the original and the remake, bears close kinship to Burton’s first professional cinematic production, the six-minute black-and-white stop-motion Vincent, written, designed, and directed by Burton while working as a conceptual artist at Walt Disney Animation Studios. In the short, which is narrated by Vincent Price himself, Vincent Malloy is a seven-year-old boy who wishes to be like Vincent Price and is obsessed with the Gothic tales of Edgar Allan Poe. His reading and viewing prompt him to conjure up a variety of dark fantasies—seemingly influenced by Poe’s “Berenice” (1835) and “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1939); for example, he fantasizes that he has buried his wife alive (which leads him to dig up his mother’s flower garden); he experiments on his dog, Abercrombie, seeking to transform him into a zombie; he imagines that he has been entombed in his room for years; and, at the end, quoting from Poe’s “The Raven” (1845), he fantasizes his own madness and death—seemingly preferring this to playing outside in the sun with other children. What is particularly fascinating about Vincent is precisely how “Burtonesque” this six-minute film from the beginning of his career actually is; present within the film in embryo are multiple themes and motifs that Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Mainstream Outsider: Burton Adapts Burton ● 5 resonate throughout the body of Burton’s work. Vincent is a wild-haired outsider attired in horizontal stripes who views his world through the imaginative lens afforded by classic Gothic texts and films. Although urged by his mother to “get outside and have some real fun,” Vincent—like Victor in Frankenweenie—isn’t interested in participating in “normal” suburban life and eschews the sun in favor of dallying with darkness. Vincent, the narration informs us, “doesn’t mind living with his sister, dog and cats.” However, “he’d rather share a home with spiders and bats/There he could reflect on the horrors he’s invented/And wander dark hallways, alone and tormented.” In this, Vincent is the prototype for Burton’s characteristic imaginative outsider protagonists—among them, Lydia Deetz (Winona Ryder) in Beetlejuice (1988), Michael Keaton’s Batman in Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992), and just about every character played by Johnny Depp across Burton’s oeuvre. Most striking about Vincent, however—and linking it across Burton’s career to 2012’s Frankenweenie—is its distinctly Burton-esque Expressionistic aesthetic. Within Vincent, forms are elongated and disproportionate, and straight lines are eschewed in favor of jagged teeth-like stairs, wobbly banisters, and tilting walls. This Expressionistic aesthetic finds repeated emphasis in Burton, from the afterlife in Beetlejuice to the Penguin’s lair in Batman Returns to the hellish basement in Sweeney Todd (2007) to Burton’s characteristic chiaroscuro lighting in almost all of his work (see Pomerance in this collection). This aesthetic is realized throughout the black-and-white Frankenweenie, from extreme contrasts of black and white to the abstractionism of the characters’ large white eyes trapped in rings of white to the “angular shadows and architecture that stretch through the town” (Wade) (Figure i.2). Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985) Pee-wee Herman in Burton’s full-length directorial debut is a perpetual child who delights in toys, Rube Goldberg breakfast-making machines, and, above all, his bicycle. The novelty of Pee-wee is that, unlike the conventional Hollywood psychosocial narrative of the child propelled into adulthood as a result of a traumatic loss, Pee-wee is not forced to grow up at the end—nor is this childish persistence a form of fantastic disavowal. Rather, he exists within a carnivalesque cartoonish world in which adults act like children and plenitude is possible. Pee-wee is not an alienated loner disgruntled with the world and cursed by fate like Batman or Sweeney Todd; nor is his world enlarged through an encounter with a parallel universe (although Large Marge is pretty scary) as in Sleepy Hollow (1999) and Alice in Wonderland (2010). Pee-wee rather is a quester supported in his venture by the forces of the universe and Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 6 ● Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock Figure i.2 An Expressionistic image from Vincent rewarded in the end with fulfillment—and in this, Pee-wee is unusual among Burton’s films.3 A direct link between Frankenweenie and Pee-wee is the bicycle wheel. In both films, Burton exploits the symbolic connection of the bicycle with childhood and uses it to frame parallel narratives concerning the restoration of a loved object and the childish denial of the possibility of true loss. Peewee, as noted above, is an eternal child who delights in toys, games, gags, and, more than anything, his prized bicycle, which is central to the film. The film opens with Pee-wee dreaming of winning the Tour de France. He later does tricks on his bike in the park and feverishly dreams of the bike being melted down by the devil before the film culminates with an extended chase sequence through the back lot of Warner Studios as Pee-wee reclaims his stolen bicycle. The final shot of the film (in a nod toward Spielberg’s E.T ., released three years earlier) shows the silhouettes of Pee-wee and Dottie (Elizabeth Daily) bicycling across the screen at a drive-in where a “Hollywoodized” version of Pee-wee’s story featuring James Brolin as Pee-wee is being shown. While Pee-wee’s invitation to Dottie at the end to join him as they ride off possibly suggests the onset of adult sexuality for him, the restoration of the bicycle and its privileged place in Pee-wee’s life undercuts this, indicating that the status quo ante has been restored and Pee-wee’s childish existence in which true loss Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Mainstream Outsider: Burton Adapts Burton ● 7 plays no role continues—in other words, Pee-wee continues blissfully to roll along, not headed anywhere in particular. Frankenweenie’s parallel rendering of this image is especially compelling when juxtaposed with Pee-wee’s because not only do both films connect the bicycle to the childish disavowal of loss, but they also do so in ways that foreground the suturing of the cinematic experience. At the beginning of Frankenweenie, Victor has premiered his latest cinematic creation, an Ed Wood-esque B film entitled MONSTERS from BEYOND, only to have the film stock melt against the projector lamp. Retreating to his attic studio, he repairs the film, sets it on the projector, and gives the reel a healthy spin. The spinning film reel then is superimposed over a spinning bicycle wheel as the former dissolves into the latter. The camera pulls back to reveal a paperboy making his rounds and the pastoral suburban town of New Holland. At the end of Pee-wee, “life” becomes “art” as Pee-wee’s experience is “fictionalized” in a Hollywood film and this transformation is highlighted beautifully by the silhouettes of Pee-wee and Dottie moving across the screen showing Peewee’s story. At the start of Frankenweenie, “art” becomes “life” as the cinema reel transforms into the bicycle wheel. The connection between the bicycle wheel in Pee-wee and Frankenweenie, however, becomes even more explicit during the revivification-of-Sparky sequence. Part of Victor’s apparatus consists of two bicycle wheels, each with the same spiral pattern found on the front wheel of Pee-wee’s bicycle. These spin wildly as the force of the storm is harnessed to bring Sparky back to life. In Pee-wee, the reclaimed love object is the bicycle itself; in Frankenweenie, the bicycle wheels from Pee-wee are seemingly put to use to achieve the same end: the disavowal of death and the restoration of childish faith in the possibility of plenitude. Beetlejuice (1988) In Pee-wee, Burton presents one world—a stylized version of the world we know in which eternal childhood is possible. More characteristic of Burton is the disavowal of finitude associated not with perpetual childhood but rather with life after death—and the distinctly Burton-esque ironic twist is to make the afterlife much more colorful and lively than the washed-out and vitiated land of the living. In Burton’s second full-length directorial outing, the 1988 Beetlejuice, he takes Pee-wee’s world of constant play and adds a macabre twist by shifting it to the afterlife. This then becomes a significantly recurring pattern in Burton: in general, it ironically takes death—actual death, figurative death, or the encounter with death—to restore life and a sense of playful wonder to the world. Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 8 ● Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock Beetlejuice most readily shares with Frankenweenie the conceit of life after death and gives us a full-blown vision of the afterlife—one that will be reprised with even more joie de mourir in Corpse Bride (2005): the afterlife as carnival. Rather than overlaying a patina of perpetual childhood upon the world of reality as in Pee-wee, in Beetlejuice Burton consoles the living with the fantasy that death is simply a transition to a different—and in many respects weirder and more liberating—state of being. While it is true that in Frankenweenie the afterlife is not explored, the resurrection of Sparky—who seemingly returns as his old loyal and friendly self, just with a little more “character” in the form of stitches and scars—nevertheless suggests that death is not necessarily an end. Worth noting as well is the more immediate connection between Beetlejuice and Frankenweenie established by Winona Ryder (and to a lesser extent Catherine O’Hara, who plays a mother in both films). In Beetlejuice, Ryder plays Lydia Deetz, a depressed goth teen relocated from the city to an idyllic New England town. In Frankenweenie, she voices Elsa van Helsing, a moribund goth-looking girl conscripted by her uncle, the mayor, to be the town carnival’s “Little Dutch Girl” and to sing a paean to New Holland while dressed in ridiculous outfit complete with fake blond braids and a hat sporting lit candles. Reprising Lydia’s desire in Beetlejuice to be dead like Barbara and Adam Maitland (Geena Davis and Alec Baldwin), Elsa here expresses her embarrassment as wishing to be dead. Ryder’s character in each film (and her role in Frankenweenie seems intentionally meant to reprise her role in Beetlejuice) is representative of the recurring Burton character type of the alienated individual—often, though not always, a youth (Edward Scissorhands, Ichabod Crane, Alice, and so forth)—oppressed by restrictive social expectations and jeopardized by inflexible authoritative structures. Batman (1989) The reference to Burton’s two Batman films—his third full-length directorial effort, Batman (1989), and his fifth, Batman Returns (1992)—in Frankenweenie is direct. Attempting to harness the power of an electrical storm to resurrect Sparky, Victor flies three kites from his attic laboratory, one of which is in the shape of the bat symbol, and the knowledgeable viewer of Frankenweenie can chuckle with a sense of satisfaction at the recognition of this allusion. The bat symbol here does not summon the Caped Crusader; however, it does channel from on high the powers of the elements to restore life where it has been cruelly snuffed out. Looking up at the bat signal in both Burton’s Batman films and in Frankenweenie reminds one as well that the trajectory of Burton’s films is Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Mainstream Outsider: Burton Adapts Burton ● 9 almost always literally first down then up. In Batman, the action moves from the perpetually dark streets of Gotham city to culminate at the top of a decaying Gothic cathedral and the final shot is of Batman (Michael Keaton) himself, standing at the ready atop a building as the bat signal lights up the night sky; in Edward Scissorhands (1990), Edward (Johnny Depp) emerges from and ultimately returns to a Gothic mansion that looks down up the town—also the case for Barnabus Collins (Depp) in Dark Shadows (2012). In The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), Jack’s laboratory is at the top of a tower and his flight is across the sky over the world of the living; in both Corpse Bride (2005) and Alice in Wonderland (2010), the protagonists descend to an underworld before returning; in Ed Wood (1994), Planet of the Apes (2001), and Mars Attacks! (1996), one looks to the skies as real or fictional aliens, astronauts, and flying saucers populate the screen. And in both Sleepy Hollow (1999) and Frankenweenie, the action takes the protagonists up into a precarious windmill. Edward Scissorhands (1990) Edward Scissorhands—the film perhaps most intimately associated with Burton, with the possible exception of Nightmare Before Christmas—is of course immediately connected to Frankenweenie by way of the theme of the Frankenstein’s monster. In Frankenweenie, Sparky, who sports neckline electrodes in a nod to James Whale’s films and whose very name puns on the method of his resurrection, is not built from scratch but rather is sutured and reanimated. In Edward Scissorhands, the unfinished Edward is seemingly a new entity, fashioned by his maker—played by Vincent Price—perversely out of scissors and who-knows-what in a Gothic castle overlooking the town. Both narratives, however, borrow heavily from Mary Shelley’s canonical 1818 Gothic nightmare. Perhaps less obviously but equally compellingly what links both films is the bland suburban neighborhood and most especially the hedge, symbolic of unimaginative suburban existence, conventional single-family homeownership, and the taming of nature. In Edward, Edward transforms these porous barriers separating one cookie-cutter home from the next into works of whimsy and, in the process, magically infuses the middle-class neighborhood with the freedom, individuality, and vivacity Burton associates with the world of art. In contrast, in Frankenweenie, when the town’s stern mayor— the redundantly named Mayor Burgemeister—ominously brandishes a set of hedge clippers at Sparky while warning Victor to police where his dog poops, he is presented as the antithesis of Edward Scissorhands; Mayor Burgemeister is indeed everything a Burton movie despises: a stalwart Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 10 ● Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock champion of conservative middle-class values who insists on conformity and respect for the rules. In Burton, hedges serve as symbols of middle-class conformity that exist to be either transformed into art or trampled to the ground. Batman Returns (1992) Stitches are precisely what suture together Frankenweenie and Burton’s fifth directorial offering, Batman Returns. Among the most insistent themes within Burton’s body of work is the shared exhilaration and anxiety concerning bodily transformation, and among the most notable characteristics of Burton’s imagined worlds are the sutures—the literal stitches that, often tenuously, hold the characters’ bodies together. Sparky in Frankenweenie and Sally in The Nightmare Before Christmas are literally stitched together and constantly on the verge of falling to pieces—Sparky’s tail in fact drops off, while Sally repeatedly sews herself back together. In Mars Attacks!, Natalie Lake (Sarah Jessica Parker) ends up with her head sewn roughly onto the body of her beloved Chihuahua, and it is not clear whether Edward Scissorhands even has skin beneath his black leather fetish suit. In Batman Returns, following the revelation that a power station proposed by her boss, the allusively named Max Shreck4 (Christopher Walken), will actually drain energy from Gotham City, secretary Salina Kyle (Michelle Pfeiffer) is pushed out a window. Revived by alley cats, she reinvents herself as Catwoman—and the most notable (and oft-remarked) feature of her transformation is her homemade patent leather cat suit with its prominent stitching. While it is not clear whether Salina survives her fall or is somehow magically resurrected by felines, she—like Sparky—nevertheless returns from the dead and the stitches on her second skin testify to her reanimation. The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) While The Nightmare Before Christmas was directed by Harry Selick rather than Burton, it nevertheless is so closely associated with Burton (who both co-wrote and produced the film) and bears so many of his hallmarks that some attention seems warranted here. The film itself originated in a poem written by Burton in 1982 while working as a Disney animator, and early versions of Sally and some of the monstrous denizens of Halloweentown are clearly evident in Vincent. Nightmare is connected broadly to Frankenweenie (and also to Corpse Bride) through the stylized stop-motion figures and in particular through the relationship between the residents of Halloweentown and the revivified and transmogrified pets of New Holland. Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Index Note: Letter ‘n’ followed by the locator refers to notes. Abecendarium, 153 Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, 113, 117 Abrams, J. J., 113 Ackeren, Robert van, 203 adaptation, 2, 14, 19, 23, 26, 84, 99–114, 117, 123, 125, 126, 127, 128, 130n5, 133, 138, 145, 170, 186, 187 Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp, 130 Aladdin’s Lamp, 122 Alexander, Scott, 136, 138, 146n10 Ali Baba Bound, 122 Alice (character). see Kingsleigh, Alice Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (children’s story), 26, 36, 42, 59, 61, 84, 85, 92 Alice in Wonderland (1951 film), 84, 87 Alice in Wonderland (2010 film), 5, 9, 17, 18, 21–2, 26, 29n6, 42–3, 47–8, 50, 54, 58–62, 72, 73–6, 80, 83–95, 101, 103, 111, 112, 145, 220, 228, 231 Allen, Woody, 146n7 Alma-Tadema, Lawrence, 61 Althusser, Louis, 221 Amarcord, 40 Amazing Stories, 175 American International Pictures (AIP), 120–1, 129, 130n3 Andac, Ben, 219 Anderson, Carolyn, 138, 146n7, 146n10 Anderson, Hans Christian, 152, 161, 163 animation, 83–95, 119, 170, 172, 175–6, 180, 233 Arendt, Hannah, 44 Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, 130n6 Arkin, Alan, 73 Armstrong, Alun, 14 Arnold, Jack, 130n2 Arquette, Patricia, 13, 52 Artist, the, 9, 20, 21, 23, 38, 217–30 Art of Tim Burton, The, 183 Asma, Stephen T., 23 Atta, Karen, 167 Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, 109 Atwood, Colleen, 48, 49, 50, 57, 177 auteurism, 55, 104, 107, 112, 113, 119, 127, 133, 140, 147n13, 179–92, 227, 232, 243–4 Avatar, 86 Avengers, The, 107 Bacon, Francis, 224 Bacon-Smith, Camille, 109 Badmington, Neil, 145 Baecque, Antoine de, 28n2, 102 Baker, Kathy, 36–7, 205 Baker, Roy Ward, 130n2 Bakhtin, M. M., 52, 189–90, 233 Baldwin, Alec, 8, 69, 86, 235 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 250 ● Index Bambi Meets Godzilla, 24–5, 25 Barker, Benjamin. see Todd, Sweeny Barsanti, Chris, 106 Bartel, Paul, 1 Basinger, Kim, 224 Bassil-Morozow, Helen, 119, 126, 130n6 Bataille, Georges, 200 Batman (film character), 5, 9, 20, 21, 44, 51, 53, 55, 65, 66–8, 104–5, 109, 113, 127, 133, 197, 207, 225 Batman (comic), 104, 109, 127 Batman (film), 5, 8–9, 44, 51, 52–3, 65, 67, 71, 101, 104–5, 107, 109–10, 111, 124, 125, 127, 134, 137, 146n1, 186, 217, 224–5, 238–9 Batman (television series), 104, 118 Batman Forever, 141 Batman Returns, 5, 8, 10, 44, 52, 53, 65, 101, 109, 122, 124, 125, 127, 134, 137, 182, 197, 199, 207–9, 218, 228, 229 Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon, 130n7 Bava, Mario, 102, 200 Bayer, Samuel, 106 Baym, Nancy K., 184 Beastly Baby, The, 160 Beetlejuice (character), 70, 121, 124, 190, 231, 235–40, 238 Beetlejuice (film), 5, 7–8, 13, 21, 22, 26, 28n5, 35, 47, 50, 51–2, 69–70, 80, 83, 85, 86, 114, 124, 125, 128, 134, 137, 138, 146n1, 146n9, 182, 222–3, 225, 226, 232–3, 234, 235–40, 242 Bekmambetov, Timur, 113, 117 Belafonte, Harry, 70, 80 Bello, John De, 109 Belloc, Hilaire, 123 Benton, Mike, 130n4 Berlant, Lauren, 214 Berman, Ted, 95 Bernard, James, 24 Bernardo, Susan M., 210 Bernstein, Rachel, 173 Betty Boop, 123 Biallas, Leonard J., 232 Bielby, Denise D., 179 Big Fish, 16–17, 21, 22, 28–9n5, 33, 37, 50, 85, 101, 107–9, 124, 125, 128, 218, 232–4, 240–3 Bill, Leo, 61, 73, 90 Bingham, Dennis, 139, 146n10 Biodrowski, Steve, 91 Black Cauldron, The, 95, 174 Black Sunday, 102, 200, 210 Bloody Chamber, The, 124 Bloom, Edward, 16, 21, 34, 124, 231, 240–3 Bloom, Will, 17, 108, 240–1, 243 Body Snatchers, 133 Boggs, Kim, 203–5, 221 Bogue, Ronald, 201, 208–9 Bonanza, 102 Bond, Christopher, 106, 129 Bonner, Frances, 111 Booy, Miles, 182 Boulle, Pierre, 128 Bourdieu, Pierre, 146n4 Braidotti, Rosi, 201 Brain That Wouldn’t Die, The, 120–1 Branagh, Kenneth, 107 Brecht, Bertolt, 129 Breskin, David, 48, 233 Bride of Frankenstein, The, 1, 3, 24, 128 Bride of the Monster, 11, 135, 138 Brolin, James, 6 Brooker, Will, 130n7, 186 Brooks, Mel, 125–6 Brosnan, Pierce, 13, 142 Brother Bill, 147n12 Brown, Len, 108–9 Browning, Tod, 130n2 Bruzzi, Stella, 49, 50 Bryant, Anita, 202 Burgemeister, Mr., 3, 8, 9–10, 14 Burne-Jones, Edward, 57, 58 Burnett, Frances Hodgson, 152 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Index Burton, Tim appearance, 54–5 art exhibit, 2, 28n1, 38, 120, 165–78, 180, 183–6, 219, 220 as auteur, 107, 113, 119, 147n13, 179–92, 232, 244 biography, 1, 4, 10, 38, 43, 108, 119, 122, 139, 146n8, 165–78, 180, 188–91, 200, 206, 219 color, use of, 33–45 expressionism of, 5, 6, 42–3, 50–1, 108, 118, 120, 122, 126, 129, 130n5, 173, 175 influences on, 23–5, 29n7, 38, 43, 50–1, 56, 117–29, 130nn2–3, 133–47, 151–63, 175, 191, 200 outsider status, 2, 25–7, 165–78, 180, 219, 232 space, construction of, 83–95 Burton on Burton, 139–40, 180, 219 see also Salisbury, Mark Buscemi, Steve, 242 Butler, David, 188 Buttgereit, Jôrg, 213 Cabinet of Dr Caligari, The, 51, 118, 120, 122, 174 Califia, Pat, 209 California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), 122, 165–6, 172, 173 Calloway, Cab, 79 Cameron, James, 86 Canby, Vincent, 225 Cannon, Robert, 123 Carpenters, The, 99 Carroll, Lewis, 42, 59–61, 84, 85, 87, 88, 92, 133, 154–5 Carter, Angela, 124–5 Carter, Helena Bonham, 16, 18, 19, 21, 26, 33, 37, 55, 57, 87, 88, 94, 128, 198, 211, 213 Catwoman, 10, 53, 55, 113, 126, 127, 177, 180, 197–8, 202, 207–8, 208, 218, 219, 229 Cautionary Tales for Children, 123 Cavallaro, Dani, 52 ● 251 Chaffey, Don, 130n2 Chandler, Raymond, 219 Chaney, Lon Sr., 129 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (children’s book), 18, 26, 107–8 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (film), 17–18, 21, 38, 41–2, 65, 66, 76–8, 81, 101, 107, 108, 123, 125, 127, 128, 145, 200 Charlie Brown Christmas, A, 158 Charisse, Cyd, 40 childhood, treatment of, 3–7, 11, 16, 17–18, 21–2, 23, 28n5, 65–6, 108, 151–63, 202, 206, 209–10, 239 Children’s and Household Tales, 152 Child’s Garden of Verses, A, 152 Cholodenko, Alan, 85–6 Citizen Kane, 227 Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums, 166–7 Cline, John, 146n3 Clive, Colin, 126 Clouzot, Henri-Georges, 221 Clover, Carol, 22 Cocteau, Jean, 213 Cohen, Sasha Baron, 223–4 Collins, Andrew, 225 Collins, Barnabas, 8, 21, 22, 99–100, 102–3, 105–6, 114, 117, 125, 129 Collins, Jim, 101, 118 Colossus of New York, 39 Company of Wolves, The, 124–5 Conversations with Vincent, 129 Cooper, Alice, 23, 99, 118, 130n2 Cooper, Merian C., 130n2 Corman, Roger, 121, 130n3, 138 Corpse Bride (character), 19, 21, 78, 126, 128, 198, 211–14, 213 Corpse Bride (film), 8, 9, 10, 19, 21, 22–3, 35, 121, 125, 126, 128, 177, 198, 199, 211–14, 218, 219, 220, 228, 229, 231, 233 costuming, 47–62 Cowboys vs. Aliens, 113 Crane, Ichabod, 8, 14, 16, 57, 70, 72, 108, 111, 198, 209–11, 214 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 252 ● Index Craven, Wes, 203, 204 Creature from the Black Lagoon, 130n2 Criswell, The Amazing, 11, 48, 135 Crudup, Billy, 17, 108, 240 Cruising, 203 Cruising Utopia, 200 Crypt Keeper, The, 121 Cult Cinema, 181 Cunningham, Hugh, 152 Curse of Frankenstein, The, 121 Curtis, Dan, 101, 117 Curtis, James, 120 Czapsky, Stefan, 49, 138 Dahl, Liccy, 107 Dahl, Roald, 18, 40, 107, 108, 123 Daily, Elizabeth, 6 Daly, Steve, 129 Dante, Joe, 24 Dark Knight Returns, The, 186 Dark Shadows (film), 9, 17, 18, 22–3, 49, 50, 94, 99–100, 101, 102–3, 105–6, 114, 117, 125, 129, 145, 219 Dark Shadows (TV program), 22, 26, 27, 101, 102–3, 111–12, 114, 117 Davis, Geena, 8, 52, 69, 86, 235 Davis, Jack, 123 Dawn of the Dead, 107 Day the Earth Stood Still, The, 142 DC Comics, 127, 225 Deadly Mantis, The, 40 Dean, James, 40 death, 2–3, 7–8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 23, 124, 153–5, 161, 212–14, 232, 234–40 Deetz, Delia, 222–3, 236 Deetz, Lydia, 5, 8, 28n5, 47, 49–50, 51–2, 124, 223, 225, 226, 236–7, 239–40 de la Tour, Frances, 22, 60, 90 Deleuze, Gilles, 199–201, 202, 204, 205, 208–9, 212–13 Depp, Johnny, 5, 9, 14, 18, 19, 20, 21, 26, 28n3, 33, 36–7, 37, 41–2, 48, 49, 50, 57, 65, 70, 72, 89, 99, 105, 108, 114, 118, 128, 129, 136, 138, 185, 198, 211, 213, 217, 218, 219, 227 Destroy All Monsters, 130n2 DeVito, Danny, 16, 65, 209 Dewhurst, George, 115n1 Dick, Philip K., 42 Dickens, Charles, 60, 152, 162–3, 211 Diebenkorn, Richard, 43 Dien, Casper Van, 209 Di Novi, Denise, 49 Disney, Roy, 84, 172 Disney, Walt, 43, 84, 123, 172 see also Walt Disney Productions Disneyland, 43 Disney Channel, 1, 125, 175, 187 Doctor of Doom, 130n3 Donnelly, Kevin J., 67 D’Onofrio, Vincent, 12, 140 Doré, Gustav, 129 Doty, William, 232, 240 Doueihi, Anne, 240, 243 Dracula (literary character), 125 Dracula (1931 film), 130n2, 169 Dracula: AD 1972, 118 Dracula Has Risen From the Grave, 102 Dreyer, Carl, 127 Dr Jekyll and Sister Hyde, 130n2 Duggan, Lisa, 215n3 Duncan, Carol, 166–7 Duncan, Lindsay, 21, 47 Dunlop, Blair, 17 Dürer, Albrecht, 35–6, 37 Duvall, Shelley, 1, 130n5 Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, 108, 142 Ebert, Roger, 225 EC Comics, 121, 130n4, 143 Eco, Umberto, 183 Edelstein, David, 54, 206, 233 Edmundson, Mark, 25 Edwards, Blake, 213 Edward Scissorhands, 9–10, 19–20, 22, 36–7, 43–5, 49–50, 53–5, 57, 72–3, 80, 84, 101, 113, 125, 126, 128, 129, 134, 137, 167, 182, Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Index 187–8, 191, 198, 199, 202–7, 217, 218–23, 225, 226, 228–9 Ed Wood, 9, 11–13, 17, 24, 26, 28n3, 35, 48–50, 51, 52, 84, 121, 125, 127, 133–42, 144, 146, 146n2, 146–7nn10–12, 191, 197, 214n1, 217, 226–8 Eisenstein, Sergei, 119 Elfman, Danny, 49, 50, 65–81, 114, 142, 144, 147n14, 167, 233 Elliott, Kamilla, 103 Emily (Corpse Bride character). see Corpse Bride (character) Emmerich, Roland, 119, 145 Empire Online, 225 Enchanted, 85 Englund, Robert, 204, 229 Enholm, Molly, 206, 215n2 Estes, Richard, 43 E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, 6 Everglot, Victoria, 18 Expressionism, 5, 6, 42–3, 50–1, 120, 121, 122, 126, 127, 129, 175 fairy tales, 1, 56, 60, 66, 72–6, 120, 122, 124, 128, 129, 130n5, 152–3, 175, 202, 219 Fall of the House of Usher, The, 121 Family Dog, 175–6 family values, 22, 23 Fandom, 100, 102, 103–6, 108–14, 127, 130n7, 134–6, 139, 145, 177–8, 179–92 Father Knows Best, 169 Favreau, John, 113 Fellini, Federico, 39–40, 209 Ferenczi, Aurélien, 28n2, 105, 119, 128, 130n8, 180, 233 Ferretter, Luke, 221 Ferretti, Dante, 56 Fiend of Fleet Street, The, 128 Finlay, Victoria, 34 Finney, Albert, 16, 34, 218, 240 Fisher, Terence, 121 Fleming, Victor, 38 Fleischer, Dave, 84 ● 253 Fleischer, Max, 84, 123 Flinn, Caryl, 67 Foster, Harve, 84 Foucault, Michel, 180, 186, 188, 198 Fouché, Joseph, 106 Fowkes, Katherine A., 188, 238 Fox and the Hound, The, 95, 173 Francis, Freddie, 102 Fraga, Kristian, 28n2, 48, 49, 54, 125, 126, 174, 177, 190 Frankenstein (1931 film), 1, 24, 56, 120, 121–2, 125, 126, 169, 177, 222 Frankenstein (novel), 1, 2, 53, 125, 128 Frankenstein, Victor (Frankenweenie character), 2–3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 16, 18, 20, 24, 25, 26, 124, 126, 129 Frankenweenie (1984), 1–4, 101, 117, 119, 124, 125–6, 127–8, 184, 187, 188 Frankenweenie (2012), 1–27, 101, 113, 117, 118, 125–6, 127–8 Frank, Scott, 42 Freud, Sigmund, 60, 204 Freunde, Karl, 129 Frid, Jonathan, 105, 114, 117 Friedkin, William, 203 Frierson, Michael, 138 Fuller, Graham, 118–19, 204 Furby, Jacqueline, 188 Furst, Anton, 125, 225 Gabler, Neal, 84, 123, 130n1 Gambon, Michael, 72 Gamera, 3, 13 Gans, Herbert, 146n4 Gashlycrumb Tinies, The, 123, 153, 155 Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., 240 Geisel, Theodor Seuss, 118, 122–3, 171 Gelman, Woody, 108–9 Genet, Jean, 146–7n11 Genette, Gérard, 101 Geraghty, Christine, 102, 103 Gerald McBoing-Boing, 123 Ghandi, 139 Ghoulardi, 121 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 254 ● Index Ghoul, Tarantula, 121 Giant Zlig, The, 171, 173, 175 Gibson, Alan, 118 Girard, René, 221–2 Glen or Glenda, 11, 135, 137, 140 Glover, Crispin, 87, 93 Godard, Jean-Luc, 136 Goddard, Peter, 219 Godzilla (film), 26, 130n2, 228 Godzilla (monster), 12, 24, 228 Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, 35, 36, 37 Goings, Ralph, 43 Golden Turkey Awards, The, 136 Goldman, Michael, 87, 89 Gombrich, E. H., 35, 36 Gone With the Wind, 105 Gorbman, Claudia, 68, 69–70 Gore, Edgar “E,” 3, 24 Gorey, Edward, 123, 151–63 Gothic (architecture), 35–6 Goth (subculture), 51–2, 53–5, 57, 124, 138, 191, 202, 223, 236 Gothic (genre), 2, 4–5, 9, 17, 20, 23–7, 35, 51, 54, 55, 56–7, 60, 61, 70–2, 78, 80, 102, 107–8, 111, 114, 117–29, 145, 191, 213 Graham, Allison, 135–6 Grahame-Smith, Seth, 117 Grant, Catherine, 186 Grant, Richard E., 19 Gray, Jonathan, 180 Green, Eva, 22, 125 Green, Joseph, 120 Green Beads, The, 151 Gremlin, 3, 13, 24 Gremlins, 24 Grey, Rudolph, 126, 136, 146n6 Grieg, Edvard, 70 Grimm Brothers, 152, 175 Gross, Ed, 103, 111–12 Guattari, Félix, 208 Haas, Lukas, 13 Halfyard, Janet K., 67, 68, 70, 71 Hall, Arch, Jr., 134 Hammer Studios, 20, 23–4, 56, 102, 121, 129, 191, 200 Hannaham, James, 51 Hansel and Gretel, 1, 119, 125, 130n5, 175 Hantke, Ken, 137, 141–2, 143, 146n8, 147n17, 200, 205, 209 Hapless Child, The, 151 Harryhausen, Ray, 142, 170 Hathaway, Anne, 36, 42, 89 Hattenstone, Simon, 55 Haunt of Fear, The, 121 Hawkins, Joan, 137 Hayward, Philip, 80, 133, 142, 144, 147n14 Hazel, Harry, 106 He, Jenny, 50–1, 120, 166 Headless Horseman, 27, 70–1, 89, 211 Heathcote, Bella, 22 Heinrichs, Rick, 49, 50 Herman, Pee-wee, 5–6, 16, 124 Hermes (god), 240, 241, 242 Herrmann, Bernard, 67, 142 Hickey, William, 79 Hickson, Julie, 1, 125 Highmore, Freddy, 76 High Spirits, 124–5 Higson, Andrew, 55–7 Hills, Matt, 111, 181, 183, 187 Hilton, Ken, 122 Hines, Claire, 188 History of Sexuality, 198 Hitchcock, Alfred, 40, 201 Hoberman, J., 142–3 Hockney, David, 43 Holder, Geoffrey, 76 Holmes, Sherlock, 102 H(ome) B(ox), O(ffice), 121 Home Video, 134, 136, 137, 140 Hopkinson, Martin, 39 Honda, Ishirō, 13–n2 Horn, John, 107 Horowitz, Josh, 103 Horror of Dracula, The, 24, 26, 121 Houdini, 170 Houdini, Harry, 170 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Index House of Wax, 122 Howard, John, 40 Hughes, Kathleen, 104 Hunter, Nan D., 215n3 Hunter, Tim, 119 Huston, John, 127 Hutcheon, Linda, 26, 101 Hyde, Lewis, 232, 234, 239, 240, 241, 242 Hynes, William J., 232, 234 In a Glass Darkly, 127 Incredibly Strange Films, 135, 136 Independence Day, 133, 145 Inner Sanctum Mysteries, 121 Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, 166 Invisible Man, The (film), 24 Irony (Gothic), 26–7 Irving, Washington, 14, 26, 133, 209–10 Island of Dr. Agor, The, 170 It Conquered the World, 130n3 Jabberwocky (film), 21, 26, 62, 66, 75, 89, 92, 93 “Jabberwocky” (poem), 154–5 Jack Sheppard, 128 Jackson, Rosemary, 125 Jackson, Wilfred, 84 Jacobs, Jason, 111 James, Edward, 69 James, Geraldine, 90 James and the Giant Peach (film), 123 Jameson, Fredric, 120 Jason and the Argonauts, 130n2 Jenkins, Henry, 181, 182, 184 Jessica’s First Prayer, 152 Joker, The, 52–3, 66, 68, 109–10, 111, 126, 127, 177, 217, 224–6, 238–9 Jones, Alan, 51, 104, 125 Jones, Jeffrey, 11, 14, 48–9, 236 Jones, O-Lan, 223 Jones, Terry, 199, 203 Jones, Tom, 144 Jordan, Neil, 124–5 ● 255 Jung, Carl Gustav, 130n6, 231 Juno, Andrea, 135, 136, 140 Juran, Nathan, 40, 130n2 Kandinsky, Wassily, 40 Kane, Bob, 104, 107 Karaszewski, Larry, 136, 138, 146n10 Karloff, Boris, 24, 123, 126, 177 Kassabian, Anahid, 68 Kaufman, Andy, 146n10 Keaton, Michael, 5, 9, 65, 70, 72, 104–5, 121, 127, 197, 238 Kelljan, Bob, 130n2 Kelly, Laura Michelle, 128 Kerenyi, Karl, 232, 234 Kersten, Annemarie, 179 Kervorkian, Martin, 209–10 Killing Joke, 186 King, George, 115n1, 128 King, Stephen, 126 King Kong, 130n2, 169 Kingsleigh, Alice, 8, 21–2, 26, 29n6, 36, 47, 54, 58–62, 65, 73–5, 85, 88–95, 95, 103, 111, 124, 220 Kingsley, Charles, 152 Kosinski, Joseph, 85 Krauss, Werner, 123 Kroger, T. Jeanette, 171 Krueger, Freddy, 204, 205, 229 Krzywinska, Tanya, 199 Kurtzman, Harvey, 123 Kyle, Selina. see Catwoman Lacan, Jacques, 65–6, 74 Laemmle, Carl, 120 Lambert, Mary, 25 Landau, Martin, 1, 14, 24 Landis, Deborah Nadoolman, 49, 50, 51 Lang, Fritz, 225 Latham, Rob, 146–7n11 Leave It to Beaver, 169 Lee, Christopher, 14, 17, 24, 191 Lee, James Hiroyuki, 24 Le Fanu, Joseph Sheridan, 127 Lefebvre, Henri, 83, 86, 92 Legend of Sleepy Hollow, 102 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 256 ● Index “Legend of Sleepy Hollow, The.” see Irving, Washington Legros, Alphonse, 40, 41 Leitch, Thomas, 101, 105, 107 Le Mystère Picasso, 221 Leni, Paul, 120 Lethal Weapon, 139 Lewis, Herschell Gordon, 134 Liddell, Alice, 61 Liebesman, Jonathan, 106 Lima, Kevin, 85 Lisberger, Steven, 85 Little Dead Riding Hood, 174 Little Princess, A, 152 Little Shop of Horrors (1960 film), 130n3 Lizardi, Ryan, 112 Lloyd, Edward, 128 London: A Pilgrimage, 129 Lone Ranger, The, 106 Lord of the Rings, The, 105 Lorre, Peter, 129 Lourié, Eugène, 39 Luau, 130n3 Lucas, Matt, 87 Lugosi, Bela, 11, 24, 48, 127, 135, 138, 146n8 Lupo, Jonathan, 138, 146n7, 146n10 Lustig, Aaron, 73 Lynch, David, 147n13 Lyne, Adrian, 199 MacDowell, Michael, 128 Mad Hatter, 21, 26, 33, 42, 50, 61, 89, 93 Mad Love, 129 Mad Monster Party, 3, 123 Madonna, 202–3 Magliozzi, Ron, 50–1, 120, 152, 166, 172 Mair, Jan, 145 Maitland, Adam, 8, 26, 28n5, 52, 69–70, 86, 235–40 Maitland, Barbara, 8, 26, 28n5, 52, 69–70, 86, 235–40 Maîtress, 203 Malcolm X, 139 Malevich, Kazimir, 40 Malloy, Vincent, 4–5 Mannix, Daniel P., 95 Man on the Moon, 146n10 Mapplethorpe, Robert, 203, 210 Marangoni, Tranquillo, 40, 41 Maria Marten, 128 Marie, Lisa, 177, 210 Markley, Robert, 203 Marling, Karal Ann, 43 Mars Attacks!, 9, 10, 12–14, 50, 80, 85, 101, 108–9, 121, 133–4, 142–6, 143, 146n2, 147n18, 169, 191 Martin, David, 34 Mary Poppins, 84 Mary Reilly, 137 Matthews, J. Clive, 1, 28n2, 108, 197, 203, 209, 210 Mathijs, Ernest, 146n5, 181, 183, 191 Maturin, Charles, 117–18 McCay, Winsor, 84 McGrath, Gulliver, 22 McGregor, Ewan, 16 McGrory, Matthew, 16, 242 McKean, Dave, 130n6 McKenna, Kristine, 111 McMahan, Alison, 28n2, 110, 119, 130n1 Medved, Harry, 136 Medved, Michael, 136 Meese Report, 202 Melancholy Death of Oyster Boy & Other Stories, The, 123, 126, 151–2, 155–63, 167, 168 Mellamphy, Deborah, 146–7n11, 214n1 Mendlesohn, Farah, 69 Menzies, William Cameron, 39 Meyer, Stephanie, 111 Middleton, Thomas, 129 Mighty Mouse, 122 Miller, Frank, 186, 208 Miller, Jonny Lee, 22 Miller, Julie, 106 Milligan, Andy, 115n1 Milton, John, 128 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Index Minority Report, 42 Mitchell, John Cameron, 206 Moby Dick (film), 127 Moers, Ellen, 60 Mondrian, Piet, 169 Monk, Claire, 181 Monsters, 3, 10–11, 12, 13–14, 15, 16–17, 22–4, 26, 113, 124, 125, 126, 153–63, 242 Moore, Alan, 109, 186 Moretz, Chloë Grace, 18 Morrison, Grant, 130n6 Mothra, 24 MTV, 202 Muir, Kate, 62 Mulholland Drive, 147n13 Munich, Adrienne, 49 Muñoz, José Esteban, 200, 201–2, 213 Murnau, F. W., 28n4, 118, 122, 126 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), 2, 120, 165, 180, 183–6, 219, 220 Music, 65–81 Nabokov, Vladimir, 33, 34 Nashawaty, Christopher, 54, 200 Nasr, Constantine, 105 Nekromantik, 213 Newland, Merv, 24–5 Newley, Anthony, 41 New York Times, 225 Nicholson, Jack, 52, 109, 142, 217, 224, 225, 238 Nightmare Before Christmas, The, 3, 9, 10–11, 16, 21, 38, 50, 53, 76, 78–80, 113, 119, 123, 126, 127, 137, 177, 190, 218, 219, 227–8, 232–5, 238, 242 Nightmare on Elm Street, A, 106, 204, 229 Nine 1/2 Weeks, 199 Nixon, Richard, 99 Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens, 28n4, 122, 126 Nostalgia (Gothic), 26–7 Novak, Kim, 40 Novi, Denise De, 123 ● 257 O’Brien, Harvey, 137, 140 O’Doherty, Brian, 166, 168 O’Hara, Catherine, 1, 8, 78, 79, 222, 236 see also Deetz, Delia Oliver, Barret, 3 Oompa Loompa, 41, 76, 81 Orpheus, 213 Orr, Philip, 208 Owen, Peter, 56 Owens, Jesse, 219 Oz the Great and Powerful, 106 Padva, Gilad, 205 Page, Edwin, 28n2, 119, 138, 200, 203, 211, 213 Page, Ken, 79 Paradise Lost, 128 Parker, Sarah Jessica, 10, 11, 13 Parker, Lara, 114 Parody, 13, 17, 78, 139, 224 Party Girl, 40 Pastoureau, Michel, 34–5 Peck, Gregory, 127 People vs. Larry Flint, The, 146n10 Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, 5–7, 8, 26, 28n3, 126, 134, 137, 146n1, 233 Penguin, The, 5, 53, 65, 66, 123, 177, 180, 209 People Under the Stairs, 203 Perfect Moment, The, 203 Personal Connections in the Digital Age, 184 Personal Services, 199, 203 Pet Sematary, 25 Pfeiffer, Michelle, 10, 53, 197, 218, 229 Phantom of the Opera, The, 169 Picasso, Pablo, 242 Pierce, Jack, 126, 177 Pigott-Smith, Tim, 21, 90 Pinocchio, 1, 126 Pisters, Patricia, 201 Pitt, George Dibden, 106, 128 Pizzello, Stephen, 99 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 258 ● Index Planet of the Apes, 9, 15–16, 17, 18, 26, 50, 86, 101, 110–11, 113, 125, 128, 145 Plan 9 from Outer Space, 11, 13, 14, 117, 135, 136, 137, 139–40, 141, 147n12, 226–7 Poe, Edgar Allan, 4, 118, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 138 Pollock, Griselda, 220 Porky Pig, 122 Postmodernism, 27, 57, 67, 99, 120, 126, 127, 142 Poverty Row, 84, 135, 145 Powell, Bob, 108–9 Powell, Jemma, 18 Prawer, S. S., 127 Prest, Thomas, Peckett, 106, 128 Price, Victoria, 118, 121, 129 Price, Vincent, 4, 9, 14, 24, 26, 44, 50, 118–19, 121–2, 124, 129, 130n2, 130n5, 138, 169, 175, 191 Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, 113 Prince (musician), 223 Prometheus, 106 psychoanalysis, 205, 208, 240 see also Freud, Sigmund Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film, The, 134, 136, 146n3 Psychotronic Video, 146n3 Pulp Fiction, 203 Punk, 67, 202 Queer Child, The, 199–200 Queerness. see sexuality Radcliffe, Ann, 60, 117 Raimi, Sam, 106 Rankin/Bass Productions, 118, 123 Raskovsky, Yuri, 107 Rathbone, Basil, 102 Raven, The (film), 121 “Raven, The” (poem), 122, 124 Ray, Nicholas, 40 Rebel Without a Cause, 40 Rees, Jerry, 130n3 Reid, Jennifer, Reimagining. see adaptations Remakes. see adaptations Renoir, Jean, 39 Reubens, Paul, 79 Revenger’s Tragedy, The, 129 Ricci, Christina, 209 Rich, Richard, 95 Richardson, Miranda, 57, 59, 210 Rickman, Alan, 20, 21, 92, 129 Riley, Brian Patrick, Ring, The, 187 Ringu, 187 Ringwood, Bob, 51, 53, 177 River’s Edge, 176 Robin Hood, 106 Romero, George, 107 Rosenbaum, Jonathan, 142 Rota, Nino, 67 Roth, Tim, 128 Rowling, J. K., 111 Roy, Deep, 76 Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, 123 Ryder, Winona, 1, 3, 5, 8, 51–2, 203, 221, 223, 236 see also Boggs, Kim; Deetz, Lydia Rymer, James Malcolm, 106, 118 Sacher-Masoch, Leopold von, 202, 204 Sade, Marquis de, 204 Salisbury, Mark, 28n2, 51, 52, 56, 89, 95, 110, 114, 120, 122, 124, 126, 127, 134, 137, 138, 139–40, 142, 145, 146n9, 147n16, 169, 172, 173, 175, 180, 200, 206, 209, 210, 213, 214, 219, 228, 233 Sally (Nightmare Before Christmas), 10, 50, 53, 54, 78–9, 113, 126, 234–5 Sanders, Ed, 128 Sandvoss, Cornel, 182, 183 San Francisco Chronicle, 203 Saunders, Norman, 108–9 Schaefer, Eric, 146n3 Schneider, Karen, 145 Schoedsack, Ernest B., 130n2 Schönberg, Claude-Michel, 79 Schreck, Max, 28n4, 105 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Index Schroeder, Barbet, 203 Schwartz, David, 107 Science, 11, 14–16, 38 Scissorhands, Edward, 8, 9, 10, 19–20, 21, 37–8, 42, 43–5, 49–50, 51, 53–4, 55, 65, 66, 72–3, 108, 118, 124, 126, 128, 138, 139, 166, 167, 177, 182, 185, 190, 198, 202, 203–7, 217, 218–23, 225, 228–9 Sconce, Jeffrey, 134–5, 136, 146nn3–4, 226–7 Scott, Kathryn Leigh, 114 Scott, Ridley, 106 Scream Blacula Scream, 130n2 Sears, Fred F., 108 Secretary, 199 Seekatz, Johann, 36, 37 Selby, David, 114 Selick, Harry, 10, 123, 233 Senses of Cinema, 219 Seuss, Dr. see Geisel, Theodor Seuss Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, The, 130n2 Sex and the Cinema, 199 Sex Pistols, The, 202 Sexton, Jamie, 146n5, 181, 183, 191 Sexuality, 197–214 Shadi, Glenn, 223 Shaffer, Atticus, 3 Shainberg, Steven, 199 Shelley, Mary, 1, 2, 9, 24, 126, 128 Short, Martin, 3, 24 Shortbus, 206 Sidney, Sylvia, 13 Sixth Sense, The, 236 Skellington, Jack, 9, 16, 78, 174, 180, 218, 219, 227–8, 231, 233–5, 241 Slaughter, Tod, 115n1, 128–9 Sleepy Hollow, 5, 9, 14–15, 16, 22–3, 28n4, 35, 36, 50, 55–7, 69, 70–2, 84, 89, 101, 102, 111, 121, 125, 126, 188, 191, 198, 199, 209–11 Smith, Allan Lloyd, 56 Smith, Jim, 1, 28n2, 108, 197, 203, 209, 210 Smith, Justin, 182 ● 259 Smith, Liz, 76 Smith, Victoria, 209 Snyder, Zack, 107 Social Network Sites, 181–92 Sommers, Stephen, 119 Sondheim, Stephen, 19–20, 106–7, 128, 129, 145 Song of the South, 84 Sonnenfield, Barry, 119 Sparky (Frankenweenie character), 2–3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 18, 24, 113, 126, 127–8, 129 Species, 133 Spielberg, Stephen, 6, 42, 146n7 Spinks, C. W., 240 Stäheli, Urs, 144 Staiger, Janet, 179, 185 Stainboy, 38 Stalk of the Celery Monster, 122, 130n3, 172–3 Stam, Robert, 101 Star Wars, 183 Steele, Barbara, 210 Stern, Daniel, 1 Stevenson, Robert, 84 Stevenson, Robert Louis, 152 stitches, 8, 10, 13–14, 20, 50, 53, 113, 126, 127, 177, 218, 229 Stockton, Kathryn Bond, 199–200 Stop Motion, 1, 3, 4, 10, 78, 117, 118, 123, 126, 142, 170, 176–7, 211, 233 Streitenfeld, Marc, 106 Stretton, Hesba, 152 Stribling, Melissa, 24 Strickfaden, Kenneth, 126 String of Pearls: A Romance, The, 128 Stuart, Mel, 40, 108 Sturrock, Donald, 40 Suburbia, 9–10, 38, 54, 72, 83–4, 113, 126, 167, 169–70, 174, 206, 218 Sunset Stages, 135 Surrealism, 60 Sweeny Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1936 film), 129 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 260 ● Index Sweeny Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (Burton film), 5, 19–20, 37, 37, 50, 55–7, 101, 106–7, 122, 125, 128, 129, 145, 179, 218, 223–4, 226, 228 Tahan, Charlie, 3 Tai, Ada, 16 Tai, Arlene, 16 Tales from the Crypt, 121 Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, 122 Tallerico, Brian, 49 Tarrantino, Quentin, 203 Tenniel, John, 60, 62 Tex, 119 Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning, 106 Textual Poachers, 182 Thompson, Caroline, 49 Thompson, Maggie, 104 Thor, 107 Thumbelina, 161 Tim Burton Collective, The, 181–91 Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride. see Corpse Bride Tirard, Laurent, 217 Tissot, James Jacques Joseph, 40, 41 Todd, Sweeney, 5, 20, 27, 106–7, 108, 113, 124, 126–7, 128, 185, 218, 219, 223–4 Todorov, Tzvetan, 125 Tolkien, J. R. R., 111 Tomb of Ligeia, The, 121 Toronto Star, 219 Toth, André de, 122 Touchstone Pictures, 133, 137 Trash Cinema, 133–47 Trashola, 134 T. Rex (band), 99 Trick or Treat, 174–5, 184 Trickster, 231–44 Tron, 84–5 Tron: Legacy, 85 Tryon, Charles, 181, 183 Twilight, 105 Underland, 21, 60, 84, 85, 86, 87–94, 103 Universal Studios, 120, 126, 129, 135, 177 (Untitled) Tim’s Dreams, 170 Vale, V., 135, 136, 140 Vampira, 48, 121, 135 Vampire Diaries, The, 105–6 Vampyr, 127 Van Dort, Victor, 18, 19 van Helsing, Elsa, 3, 8 Vault of Horror, The, 121 Veidt, Conrad, 120 Velázquez, Diego, 224 Venturi, Robert, 120 Venus in Furs, 202, 204 Verbinski, Gore, 106 Vertigo, 40 Victor/Victoria, 213 Vidler, Anthony, 92 Videogames, 129 VideoHound’s Complete Guide to Cult Flicks and Trash Pics, 136–7 Vincent, 1, 4–5, 6, 10, 12, 17, 18, 26, 38, 39, 60, 95, 118–19, 121–4, 125–6, 129, 138, 175, 180, 183, 191 Vries, Hilary de, 104–5 Wade, Joseph, 5 Wahlberg, Mark, 15, 18, 86, 128 Walken, Christopher, 10, 28n4, 229 Wallace, Daniel, 101, 107, 124 Walt Disney Productions, 1, 2, 4, 10, 26, 84, 95, 102, 118–19, 122, 123, 124, 126, 133–4, 138, 141, 166, 169, 171, 173–6, 180, 184, 190 Warhol, Andy, 43, 184, 219 Warner Bros. Studios, 6, 104–5, 122, 126, 141, 144–5, 169, 186 Warner, David, 18 Warwick, Alexandra, 52 Wasikowska, Mia, 18, 29n6, 47, 61, 65, 85, 95, 220 Water-Babies, The, 152 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822 Index Waters, John, 146–7n11 Watson, Emily, 18, 212 Wayne, Bruce, 108, 111, 127, 207–8 Wegner, Philip, 144, 147n19 Weill, Kurt, 129 Weine, Robert, 120 Weiner, Robert G., 146n3 Welch, Bo, 49 Weldon, Michael, 134, 146n3 Welles, Orson, 140, 141, 146–7n11, 227 Wells, H. G., 108 West, Adam, 118 West, Walter, 115n1 Whale, James, 1, 9, 24, 118, 120, 121–2, 125–6, 222 What Color Is Your Handkerchief, 202 Wheedon, Joss, 107 Wheeler, Hugh, 19, 106–7, 128, 129 Whitman, Slim, 13, 80, 109, 144, 147n16 Wiegratz, Philip, 77 Wiest, Dianne, 50, 73, 206, 218 Wilder, Gene, 40–2 Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, 40–2, 108 Winckelmann, Johann Joachim, 36 Winkler, Margaret, 84 Winter, Julia, 108 Witch’s Tale, The, 121 ● 261 Wizard of Oz, The (film), 38, 159–60 Wolf Man, The, 169 Wolper, David L., 40 Wolski, Dariusz, 87 Woman in Flames, A, 203 Wonka, Willy (character, 1971 film), 40–1 Wonka, Willy (character, 2005 film), 18, 21, 41–2, 65, 66, 77, 80, 108, 113, 124 Wood, Ed (character), 28n3, 48, 49, 50, 124, 126, 136, 139–40, 197, 214n1, 217, 227–8 Wood, Edward D., Jr., 11–12, 117, 133–41, 141, 142, 146n6, 146n8, 146–7n11, 166, 191, 197, 217, 226–7 Wood, Wallace, 108–9 Woods, Paul, 28n2, 110, 119–20, 123, 126 Wright, H. Stephen, 67, 72 Wright, Lee, 61 Wuggly Ump, The, 153–5 Yarbrough, Tyrone, 109 Young Frankenstein, 125–6 Žižek, Slavoj, 37–8 Zone Books, 202 Zontar, 134 Copyrighted material – 9781137370822