Intact Skin – An Integrity Not to be Lost

advertisement

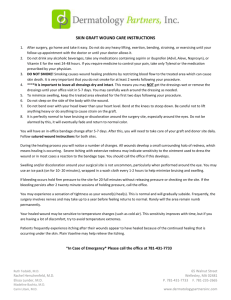

27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 27 INTACT SKIN – AN INTEGRITY NOT TO BE LOST – R. Gary Sibbald, MD, FRCPC(Med)(Derm); Karen Campbell, RN, MScN, NP/CNS; Patricia Coutts, RN; and Douglas Queen, BSc, PhD, MBA Maintaining skin integrity can be challenging but it is vital to overall health, particularly in elderly patients. In this population, skin integrity is frequently compromised as a result of under- or over-hydration, which may cause serious complications. Plans of care must include preventive efforts such as the use of barriers and protectants including zinc oxide preparations, petrolatum- and silicone-based ointments and creams, liquid-forming products, adhesive dressings, fluid managers, skin cleansers, and moisturizers. A team approach that includes the patient, caregivers, and healthcare professionals is needed to address patient concerns regarding independence/dependence, utilization of support systems and services, pain, and control of body fluids. The healthcare provider’s role in this team should emphasize continuity of care, patient satisfaction, and product selection — all vital to protecting skin integrity. Ostomy/Wound Management 2003;49(6):27–41 he skin is the body’s largest organ and performs many important functions, including protection against infectious pathogens, ultraviolet light, noxious substances, and fluid/electrolyte loss; thermoregulation; sensation; metabolism (eg, vitamin D); and communication.1,2 A breach of skin integrity can result from a variety of occurrences and cause a range of consequences, some of which can be life-threatening.3 These breaches, which can be very debilitating,4 frequently occur in the elderly because aged skin is more prone to compromise. Aging affects the skin by thinning the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous layers, as well as by reducing epidermal turnover, time to healing, injury response, barrier function, chemical clearance rate, sensory perception, immune function, vascular responsiveness, thermoregulation, and the production of sweat, sebum, and vitamin D.1,5,6 Excreted bodily fluids are responsible for the most common breaches of skin integrity in institutionalized elderly7— specifically, the consequences of fecal or urinary incontinence or presence of wound exudates on the skin.8 The body’s waste effluents can be particularly caustic to the skin. For example, fecal material contains more than 500 different organisms,9 which produce several contact irritant substances. The patient/caregiver team is primarily responsible for the maintenance of healthy skin. Many skin care T Dr. Sibbald is Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of Continuing Education, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto; and Director, Dermatology Day Care and Wound Healing Clinic, Sunnybrook and Women’s College Health Sciences, Toronto, Canada. Ms. Campbell is a Clinical Nurse Specialist, Parkwood Hospital, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario. Ms. Coutts is the Wound Care and Study Coordinator, Debary Dermatologicals, Mississauga, Ontario. Dr. Queen has a medical consultancy business, CanCARE Services Consultancy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Please address correspondence to: Douglas Queen, BSc, PhD, MBA, CanCare Services Consultancy, 35 Rosedale Road, Unit 2, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4W 2P5; email: cancare@rogers.com. June 2003 Vol. 49 Issue 6 27 27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 28 persistent skin/effluent contact occurs, whether in young or older patients, skin damage can result in diaper rash, or as it is called in the elderly, incontinent dermatitis. The prevalence of urinary incontinence in nursing homes is estimated at 50% or greater. Additional statistics from chronic care facilities show Threats to Skin Integrity urinary incontinence prevalence to be between 50% Common clinical situations that can result in damand 70%.16,17 Therefore, knowledge of the skin’s funcage to the skin include the presence of a draining wound, urinary or fecal incontinence, and the use of tion and the role incontinence plays in contact irritant 10,11 skin adhesives. dermatitis is crucial for every caregiver. Incontinent dermatitis occurs when urine comes Periwound maceration. Wounds are often excellent into contact with aged skin, which is often dry and providers of local moisture, but when present in excess cracked. This provides an excellent environment for the and allowed to contact skin, moisture can be damaging 12 growth of bacteria,18-20 resulting in the production of to the periwound area. Wound exudate often contains not only water, which in itself can be detrimental, but ammonia.21 Ammonia increases the pH of the skin,19 also cellular debris and enzymes.13 This cocktail can be reducing the acid mantle’s protective capacity as a baccorrosive to the intact skin surrounding the wound. terial barrier,19,20 subsequently providing the opportuniIn addition, dressings may leak and are often ty for chemical irritation by urine, feces, and excess changed only after leakage has occurred. As a result, the moisture to cause skin breakdown. surrounding skin is exposed to potentially damaging Fecal incontinence offers reason for greater clinician wound exudate on a continual basis.12,14 Moisture and concern.22 As feces passes through the gastrointestinal maceration will increase the skin’s permeability to irritract, digestive enzymes are deactivated. When feces tating substances, increasing the likelihood for critical mixes with urine on the skin, the urine converts to 3 microbial colonization. This can lead to delayed healammonia, and the resultant alkaline pH reactivates the digestive enzymes, further increasing the risk of skin ing, increased risk of infection, and wound enlargebreakdown and local bacterial infection.18,19 ment. Furthermore, less friction is required to damage 14 skin when it is overhydrated. When petrolatum or zinc-based products are used on patients with incontinent dermatitis, they must be Traditionally, both zinc oxide and petrolatum ointremoved and reapplied following each incontinent ments have been used to protect the periwound area.15 episode. This, in turn, can cause more skin damage due Although effective in preventing contact of wound to the friction required to remove these products. exudate with the periwound skin, this approach can Skin adhesives. Adhesive products that strip the skin interfere with dressing absorption and adhesion. also may compromise the skin’s barrier properties. These preparations are also messy to use and often These products include tapes and adhesive bandages difficult to remove.15 such as hydrocolloids, films, and some foams. Skin tack Incontinence-related dermatitis. The body is convaries among adhesive products. High-tack products stantly emitting fluid, particularly as waste excretion. If have a bonding pressure that will cause skin tears if inappropriately removed. Acrylic adhesives, priOstomy/Wound Management 2003;49(6):27–41 marily found in film dressings, are best removed KEY POINTS by pulling laterally to decrease the skin bond • Environmental and physical factors pose a continuous before lifting off the skin.23 Careful technique challenge to skin integrity, particularly in individuals with requires more caregiver time to minimize skin frail, dry, or overhydrated skin. damage. • As evidenced by this overview of products, procedures, Problems of prolonged skin contact with fluand patient, caregiver, and provider concerns related to the process of preventing skin breakdown, successful preids and their assessment and treatment are outvention efforts are broad and multifaceted. lined in Table 1. • This review serves as a reminder to practice holistically and may help institutions develop such plans of care. practices and products may help maintain integrity. The following review of the role of skin health on general health and strategies to provide effective skin care may help providers maintain skin integrity. 28 OstomyWound Management 27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 30 TABLE 1 ASSESSING AND MANAGING CORRECTABLE CAUSES AND AGGRAVATING FACTORS OF COMPROMISED SKIN Problems to Correct Issues Challenges Solutions Assess: Mobility Cognitive impairment Medication adverse effects Prevent overflow and enzymatic action; assess and determine causative factors Behavior modification Surgical intervention Pharmacological treatment modifications Establish regular bowel routine Increase bulk and fiber into stool Correct or improve causative factor Obtain wound moisture and bacterial balance Urinary incontinence Urinary containment Control odor Maintain skin integrity Fecal incontinence Fecal containment Control odor Maintain skin integrity Wound drainage Wound discharge containment Control odor Maintain skin integrity Stoma discharge containment Control odor Maintain skin integrity Fistula discharge containment Control odor Maintain skin integrity Prevent hyperhydration and increased bacterial burden of surrounding skin Keep peristomal skin intact Maintain securement of appliance to prevent leakage Divert effluent/drainage from the surrounding skin Border skin moisture control Infection control Maintain skin integrity Prevent skin breakdown Prevent bacterial proliferation Maintain access site Stoma drainage Fistula drainage Access sites leakage Physical Skin Barriers and Protectants Physical barriers. For the purpose of this review, a physical barrier is defined as a permanent interface between two surfaces to protect skin integrity. Skin barrier products have been developed for this protective need.24-26 A summary of the pros and cons of a number of these products is presented in Table 2. Zinc oxide preparations. Zinc oxide barriers — probably the most widely used barrier preparations — have been readily available for a number of years, and zinc oxide and petrolatum ointments have been routinely used to protect the periwound skin.27 For example, the most commonly used diaper rash treatments for babies are zinc oxide and petrolatum-based skin barrier products. In people with sensitive skin, such as babies and the elderly, zinc preparations are helpful. Such preparations are often robust, easily accessible, and inexpensive, making them conducive for general use. Although generally effective, significant product variability exists between preparations with regard to potential allergens (especially perfumes) and consisten- 30 OstomyWound Management Determine correct appliance with specialized expertise Determine appropriate management regimen with specialized expertise Regular assessment to ensure appropriate portal protection Ensure aseptic technique cy. This, in turn, affects their potential to damage skin.27 Zinc products are also labor-intensive, and bacterial contamination in situ is possible. Due to their robustness and permanency, they can clog containment devices, and interfere with absorbency, adhesion, and antimicrobial properties of topical treatments. Most importantly, caregivers are unable to visualize the underlying skin. Ointments/creams. Ointment preparations tend to be petrolatum-based, although recently, silicone-based creams have been introduced. The petrolatum-based products are similar to the zinc-based products discussed above — they are readily accessible, not too expensive, and widely used as skin barriers for other, less medically intense, situations (eg, as lip balms). Petrolatum-based products are also variable (35 grades of petrolatum are available) with potential added allergens and varying consistency. They tend to melt and wash off easily and, like zinc-based products, have the tendency to clog containment devices or interfere with the absorbency of dressings.28 27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 32 TABLE 2 COMPARISON OF SKIN BARRIER PRODUCTS Barrier Pros Cons Comments Liquid-forming barrier films Ease of application Uniform application Flexible and conformable Visualize underlying skin Resist wash off Do not trap contaminants Low sensitization rate Form a solid interface between two surfaces May have a long wear time Visualization of underlying skin may be possible Robust (stiff) Familiar and readily accepted Inexpensive and readily available Some contain alcohol and/or acetone (burn/sting on application) Require education regarding frequency and thickness of application Some products may allow adhesive dressings to be applied over the surface Edges may lift Trapping of moisture allows bacterial proliferation Adhesive allergies Smell/odor may occur Potential allergens and variable consistency Messy and difficult to remove May become contaminated, requiring removal May inhibit absorbency and adhesion of overlying dressings/devices Potential allergens Product variability Tend to melt and wash off Often inhibit absorbency and adhesion of other devices Require frequent reapplication May need to be used with central window, requiring training and expertise Adhesive dressings (transparent films, thin hydrocolloids) Zinc oxide ointment/paste Petrolatum and related Inexpensive (petrolatum) and accessible ointments/creams Silicone-based products are more expensive but they are far less variable, easier to apply, have lower frictional resistance, and are more resistant to wash off. They are transparent, allowing visualization of the skin underneath. An important disadvantage of ointments and creambased products is user variance in application amounts and techniques and the need to reapply the product. Also, many preparations contain potential allergens such as perfumes. Liquid-forming barriers. Liquid-forming barriers are relatively new and provide important user benefits. They are flexible and conformable, easy to use, allow uniform application/distribution, resist wash off, do not trap contaminants, and provide visualization of the underlying skin. Reports indicate a lower allergic sensitization rate with some of these products when compared with traditional therapies.29 Unlike their zinc and petrolatum counterparts, some of these products work well with adhesive dressings and do not interfere with containment devices. 32 OstomyWound Management Unable to visualize underlying skin If not contaminated, no need to remove; just fill in the gaps Quantity applied varies by users Although reported to be cost-effective, the unit purchase price of liquid-forming barriers is relatively high.30 Most, but not all, contain carrier agents, such as acetone or alcohol, which can cause burning and stinging on application. A learning curve to correctly apply these preparations must be considered. Some of the newer products provide a flexible, durable, moisture-repellent film on the skin, and an alcohol-free liquid form with a variety of application options is available.30 This product can be used on sensitive infant and aged skin.23,31 Adhesive dressings. Adhesive dressings, such as films or thin hydrocolloids, are also used as skin barriers. They are applied using a picture window framing technique, where a hole is cut in the dressings to allow for the movement of effluent into a management device (eg, absorbent dressing) while protecting the wound margin. Framing the surrounding skin prevents effluent from attacking healthy skin by forming a solid interface between the two components. This approach has the benefit of providing a constant barrier that does 27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 34 TABLE 3 COMPARISON OF SKIN PROTECTANTS Protectant Pros Skin cleansers Can be effective debris Change skin pH and dry skin removers – surfactant action Known sensitizers Maintain skin surface integrity May contain allergens (perfumes, by lubricating/hydrating skin lanolins, preservatives, stabilizers) surface Moisturizers Provide inexpensive Fluid managers absorptive surface (dressings, briefs) Briefs, calcium alginates, and hydrofibers bind fluid within their structure Separates fluid/effluent from Fluid managers skin surface (containment devices) Cons Variability of product performance characteristics Absorptive foams do not lock fluid within dressing structure Need expertise for attachment and maintenance on the skin surface Cumbersome for patients to have external pouch not require frequent changing while allowing visualization of the underlying skin through the dressing. Although this approach has some advantages, some less beneficial considerations must be addressed. Dressing edge roll, lifting, and trapping of exudate or bacterial proliferation may occur. Adhesive dressing allergies are also a possibility. The typical meltdown and odor associated with some hydrocolloid dressings may be problematic.32 The learning curve and skills required for sizing and creating the drainage port must be considered. Protectants. To distinguish protectants from barriers, and for the purpose of this review, a protectant is defined as an indirect temporary technique or application to maintain the integrity of skin at high risk. A number of skin protectants have been developed and marketed, each with its own advantages and disadvantages (see Table 3). Fluid managers. Fluid managers are absorbent devices that remove fluid/effluent from the skin surface (eg, dressings, diapers, and fluid containment devices). Dressings may serve as barriers on intact skin, as well as protectants when applied over an open wound. These products are designed to remove or collect fluid and 34 OstomyWound Management Comments Overuse can cause more harm than good Important to apply after bathing while skin is damp to trap surface moisture Urea + lactic acid preps (humectants/hydrating agents should not be applied to denuded skin — burning and stinging) Should match product performance with patient needs Pouch changes should be regularly scheduled to prevent over-accumulation of fluid and odor nothing else. Although absorbent, some dressings or diapers do not wick fluid away from the skin; rather, they form a dynamic equilibrium. As a result, the fluid can be more damaging to the skin interface, causing dressing strike-through and leakage. It may be difficult to chose from among multiple devices with differences in absorptive capacity and wear time, even within the same product category. Skin cleansing. Skin cleansers or cleansing regimens are for the skin and should not be used for open wounds where they can have a detrimental effect on healing. These products are essentially designed to remove debris from the skin surface. In general, they are surfactant-based and are superior to water or saline for debris removal because they have been specifically developed for this purpose. However, using these products presents some potential disadvantages. Many contain known sensitizers (eg, perfumes). As part of their cleansing action, they change skin pH or remove its acid mantle, which can result in drying and stripping. Healthcare providers are often confused by products in this category — sterile and nonsterile, ionic and nonionic — and some are more toxic than others. Too much detail leads to confu- 27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 35 sion and misuse of products, and overuse of this class of protectant can cause more harm than good.33 Moisturizers. Moisturizers are defined as hydrators or lubricants and primarily are used to preserve suppleness and barrier function. Hydrating agents, consisting of urea or lactic acid preparations, bind moisture in the stratum corneum. Such products are comfortable and soothing and, therefore, generally preferred by patients. They need to be applied to intact skin or they may cause a burning or stinging sensation. Moisturizers are routinely used by the majority of the general population either on a regular or sporadic (eg, after sun) basis. With fragile aged skin, regular moisturizing is imperative to healthy skin maintenance. The stratum corneum requires a 10% moisture content to maintain integrity. This is often a problem for aged skin in hot, dry winter environments. Lubricants (eg, emollient creams and petrolatum) trap insensible losses of moisture, maintaining stratum corneum moisture. Vanishing creams contain little oil and will dry the skin surface with evaporation. Preparations with higher oil content are often greasy. Lanolin has high moisture retention properties, but it is an allergen. When used as a moisturizer, the product should be applied after bathing while the skin is damp, not wet (after partially drying). This helps trap any moisture in the skin as a result of bathing, providing a good reservoir for skin hydration. For the majority of users, allergic reaction is not an issue, but patients with leg ulcers have a high allergy sensitization rate.34 Many moisturizers contain allergens (lanolins, perfumes, preservatives, emulsifiers, and stabilizers are common components). However, patient-related and healthcare provider issues also affect product choice. Patient-Centered Concerns Caregivers are responsible for the maintenance of healthy skin, but this is a team responsibility,35 and the patient is the center of the team. The patient’s desires and preferences should be central to any plan of care or adherence to treatment will be low. Resolving common patient issues, such as independence over dependence, requires collaborative support from the patient’s social network and healthcare providers. Managing pain and body fluid (urine, feces, and wound drainage) and minimizing odor are important to preserving dignity. Quality of life is often a more important consideration than achieving a cure that may be unrealistic or impossible. A summary of patient-centered concerns is presented in Table 4. Independence/dependence and support systems. The loss of control of body functions is a slippery slope that can lead to the patient losing his/her independence, resulting in institutionalization. A key factor is loss of mobility.36 This loss may be enhanced by cognitive impairment or the side effects of polypharmacy.37 Urinary incontinence is cited as one of the major causes of institutionalization.38 Assessment must include the cause of the impediment, and treatment to maintain independence must be instituted when possible. Support systems must be available, preferably through family and a social network, and complemented by social service agencies. The patient must be 27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 36 TABLE 4 PATIENT-CENTERED SKIN CARE CONCERNS Concern Issues Challenges Solutions Independence/ dependence Loss of control Loss of mobility Cognitive impairment Assess independent living versus dependence (assisted living or institutions) Healthcare support systems Treat cause of impediment to maximum function in appropriate setting Promote independence where possible Make patient and caregivers significant contributors to the care plan Coordination of care across Center care around patient the continuum Lack of access to services/care Foster involvement of immedi- Assess and evaluate the available Involve potential partners ate family, significant others, options and social network Maintain activities of daily life Identify important personal gaps for Implement non-pharmacological maximal function and pharmacological management of important issues Containment of body fluids Provide security and confidence for Address and control the cause to and odor to maintain dignity optimal daily functioning minimize exudate control Social support systems Comfort and pain Control of body fluids/odors comfortable with the decision tree, and healthcare providers must discuss options for filling current gaps in the care plan. Not all situations are amenable to independent living; the healthcare providers’ communication skills and empathy will help bridge difficult life decisions when independence is lost. Patient care must be coordinated between healthcare professionals and support services. The social work and service administrators must examine the need for homemaking, volunteers, meals-on-wheels, and accessibility to care, as well as the support system for medical emergencies. When the patient’s well being cannot be ensured in the community, institutional options must be presented and difficult choices made. Comfort/pain: The patient’s point of view. Healthcare providers are reluctant to provide adequate pain relief due to the fear of addiction. As an example of pain assessment and management, clinicians can consider Diane Krasner’s pain model39 for chronic wounds, which divides the cause of pain into three categories: • Incident pain — ie, due to debridement • Repetitive pain — ie, due to dressing changes • Continuous pain — ie, due to uncorrected cause such as infection and ischemia. Pain treatment, therefore, needs to be tailored to the periodicity of pain (eg, long-acting preparations should be ordered for continuous discomfort). 36 OstomyWound Management Control of body fluids. Excess body fluids need to be controlled so the patient has the confidence to allow social interaction. The treatment of the cause may include controlling bacterial burden or frank infection, using adequate pouching or drainage devices, and providing compression therapy for venous ulcers. Healthcare Provider’s Role According to Wells, “Elder care requires an understanding of complex interactions with multiple potential intervention points: normal aging involves a gradual mix of physiological, social, and psychological changes within a nonspecific time frame and with individual variance. The sum of this defines the old.”40 Patient satisfaction is dependent on the acknowledgment of patient-centered concerns. Specialist caregivers and their teams are available to focus on eldercare. By helping the elderly maximize functioning and minimize the effects of chronic illness, the caregiver-patient collaboration promotes improved quality of life. In achieving this goal, the healthcare provider is faced with a multitude of issues. Care design must incorporate ease of use, cost-effectiveness, and be based on best clinical practices. A summary of healthcare provider concerns is presented in Table 5. Continuity of care. One of the greatest healthcare provider concerns is the need for continuity of care 27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 38 TABLE 5 HEALTHCARE PROVIDER CONCERNS FOR PATIENT SKIN CARE Concern Issues Continuum of care Need for continuity and uniformity of care across types of institution and regarding varying levels of expertise Lack of evidenced based care Best available practice Patient satisfaction Identify and understand patient issues Product selection Product selection often random and not scientifically based Ease of use/ versatility Cost containment Challenges Solutions Communication between all stakeholders by linking education, implementation, and patient care outcomes Translating evidence into practice Centralized health record across the continuum available to all healthcare professionals Allow patient to become a partner in the care plan Critically appraise evidence or lack thereof (identify gaps) Products often require Obtain experience and critical specialized expertise for evaluation of practical usage optimal use Increased public demands with Appraise and select the most cost limited human and financial effective treatment to maximize resources benefit across all types of institutions and varying levels of expertise within those institutions. The challenge is to respect individual expertise among team members, allowing each member to share his/her knowledge in a particular area. This leads to an educational process that can be linked to implementation in practice and patient outcomes. This challenge can be evaluated using Dixon’s Four Levels of Evaluation41 — perception/opinion data, competency, clinical process, and impact on patient care and health status. Through this evaluation process, a “best available practice” can translate evidence into patient care. Barriers to translating research evidence into clinical practice exist; those involved in healthcare need to decrease the traditional delay between the availability of the evidence and its application into practice.42 This can only be accomplished by optimizing communication between all stakeholders. The improved outcomes may be easier to achieve when centralized health records are available across care continuums, including home care, acute care, and long-term care. Patient satisfaction. Patient care outcomes and satisfaction are important elements for the healthcare provider to evaluate. Often, healthcare providers do not take the time to allow patients to verbalize their current problems. Through listening without interrupting,43 the healthcare provider can identify and understand the 38 OstomyWound Management Education with implementation into practice Negotiate collaborative approach to care Standardized protocols translating evidence base and expert knowledge to local practice Choose products that are healthcare provider friendly Utilize best possible treatment in a cost-effective manner patient perspective.44 This would certainly clarify issues regarding skin care and the effects this has on everyday living. Patient perspective also might include satisfaction with treatment and provision of services as well as the level of understanding patients have about their conditions. By making the patient a partner in the care decision, a collaborative process evolves that enhances the treatment outcome. Often, healthcare providers refer to patients as noncompliant when the patient does not do what the healthcare provider instructs or if the patient is asked to adhere to a specific protocol and fails to do so. If, however, the patient is included in the decision from the beginning of the treatment process and a negotiated collaborative approach is taken, noncompliance will be less of an issue and treatment outcomes will be enhanced. Product selection. Although a major component of the plan of care, the product used is often selected at random with no scientific basis. When selecting a product, Ovington and Peirce45 ask three questions about the product feasibility: 1) What are the realistic goals of care for this patient? 2) What products are available? 3) How capable is the caregiver? Ease of use/versatility. Two important areas of product selection focus around ease of use or versatility and cost containment. The healthcare provider must remember the importance of evidence ratings in this 27-41, Queen layout 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 40 decision making process. Ovington et al45 present an example of this tactic using the AHCPR guidelines for pressure ulcers.46 Their approach focuses on the use of clinical judgment to select a type of moist wound dressing suitable for the ulcer. The authors also demonstrated that studies of different types of moist wound dressings showed little difference in pressure ulcer healing outcomes.45 The same principles can be applied to skin barriers and protectants. Caregiver familiarity with ease of use and versatility of a product requires a knowledge base. Some products require more expertise for optimal use than others. Ability to obtain experience and critically evaluate the practical usage of the product will enhance appropriate product choice. Cost containment. Limited human and financial resources and an increase in public demand have made cost containment a high-priority issue. Low unit price is not necessarily the best value. The healthcare provider needs to be able to appraise and select the most cost-effective choice, which is defined as the cost of achieving a desired treatment outcome to maximize the benefit to the patient.47 Through this process, the healthcare provider can select and utilize the best treatment in the most cost-effective and efficient manner. Conclusion The skin barrier is constantly challenged with a range of irritant and allergic substances, even in healthy individuals. When health is compromised, the skin is more vulnerable to injury. The clinical challenges and consequences of assessment, treatment, and healthy skin maintenance are factors, not only in skin care, but also in overall well being. A number of barriers and protectants have been developed and marketed for the protection and maintenance of skin integrity and should be implemented as part of a comprehensive care plan that makes skin integrity a priority. Economically, prevention is better than the treatment of lost skin integrity. The basic premise here is to remember to, “treat the whole patient rather than what comes out of the hole.”48 Clinicians should not jeopardize their integrity by failing to protect the integrity of their patients’ skin. - OWM References 1. Bryant R, Wysocki A. Skin. In: Bryant R, ed. Acute and Chronic Wounds: Nursing Management. St. Louis, Mo.: 40 OstomyWound Management Mosby Year Book Inc.; 1992:1–25. 2. Sams WM. Structure and function of the skin. In: Sams WM, Lynch PJ, eds. Principles and Practice of Dermatology. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. 3. Kemp MG. Protecting the skin from moisture and associated irritants. J Gerontol Nurs. 1994;20(9):8. 4. Jirovec M, Brink C, Wells T. Nursing assessments in the inpatient geriatric population. Nurs Clin North Am. 1998;23:219–230. 5. Silverberg N, Silverberg L. Aging and the skin. Postgrad Med. 1989;86:131. 6. Gilchrest BA. Skin aging and photoaging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;(21):610. 7. Fiers SA. Breaking the cycle: the etiology of incontinence dermatitis and evaluating and using skin care products. Ostomy/Wound Management. 1996;42(3):32–34. 8. Williams C. 3M Cavilon No Sting Barrier Film in the protection of vulnerable skin. Br J Nurs. 1998;7(10):613–615. 9. Whitman DH. Intra-Abdominal Infections: Pathophysiology and Treatment. Frankfurt, Germany: Hoescht;1991:20–21. 10. Bryant RA. Saving the skin from tape injuries. AJN. 1988;88(2):189. 11. Dealey C. Using protective skin wipes under adhesive tapes. Journal of Wound Care. 1992;1(2):19–22. 12. Weir D. Pressure ulcers: assessment, classification and management. In: Krasner D, Rodeheaver G, Sibbald RG, eds. Chronic Wound Care: A Clinical Source Book for Healthcare Professionals, 3rd ed. Wayne, Pa: HMP Communications;2001:621. 13. Chen WYJ, Rogers AA. Characterisation of biological properties of wound fluid collected during the early stages of wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99(5):559–564. 14. Braden B. Risk Assessment in pressure ulcer prevention. In: Krasner D, Rodeheaver G, Sibbald RG, eds. Chronic Wound Care: A Clinical Source Book for Healthcare Professionals, 3rd ed. Wayne, Pa: HMP Communications;2001:647. 15. Phillips TJ. OW/M commentary: a clinician’s guide to common dermatological problems. Ostomy/Wound Management. 1994;40(9):70–79. 16. Ouslander J, Kane R, Abrass I. Urinary incontinence in elderly nursing home patients. JAMA. 1982;248:1194–1198. 17. Palmer MH, German PS, Ouslander JG. Risk factors for urinary incontinence one year after nursing home admission. Res Nurs Health. 1991;14:405–412. 18. Berg RW. Etiological factors in diaper dermatitis: the role of urine. Pediatric Dermatology. 1986;3:102–106. 19. Berg RW. Etiology and pathophysiology of diaper dermatitis. Adv Dermatol. 1986;3:75–98. 20. Urinary Incontinence Guideline Panel. Clinical Practice 27-41, Queen layout 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 5/22/03 4:22 PM Page 41 Guideline Number 2: Urinary Incontinence in Adults. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1992. AHCPR Publication, No. 920038. Nobel W, Somerville D. The Microbiology of Human Skin. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1974. Allman RM, Laprade CA, Noel LB, et al. Pressure sores among hospitalised patients. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1986;105:337–342. Irving V. Reducing the risk of epidermal stripping in the neonatal population: an evaluation of an alcohol-free barrier film. Journal of Neonatal Nursing. 2001;(7):5–8. Rolstad BS, Harris A. Management of deterioration in cutaneous wounds. In: Krasner D, Kane D, eds. Chronic Wound Care: A Clinical Source Book for Healthcare Professionals, 2nd ed. Wayne, Pa: Health Management Publications, Inc.; 1997:209. Coutts P, Sibbald RG, Queen D. Peri-Wound Skin Protection: A Comparison of a New Skin Barrier vs. Traditional Therapies in Wound Management. Poster at CAWC Meeting, London, Ontario. November 2001. Campbell KE, Keast DH, Woodbury GM, Houghton PE, Lemesurier A. The Use of a Liquid Barrier Film to Treat Severe Incontinent Dermatitis-Case Reports. Poster at CAWC Meeting, London, Ontario. November 2001. Sibbald G, Cameron J. Dermatological aspects of wound care. In: Krasner D, Rodeheaver G, Sibbald RG, eds. Chronic Wound Care: A Clinical Source Book for Healthcare Professionals, 3rd ed. Wayne, Pa: HMP Communications;2001:275. Grove GT, Lutz JB, Burton SA and Tucker JA. Assessment of diaper clogging potential of petrolatum based skin barriers. Poster at the 2nd National MultiSpecialty Nursing Conference on Urinary Continence, January: 21-23, 1994. Campbell K, Woodbury MG, Whittle H, Labate T, Hoskin A. A clinical evaluation of 3M No Sting barrier film. Ostomy/Wound Management. 2000;46(1):24–30. Kennedy KL, Leighton B. Cost-Effectiveness Evaluation of a New Alcohol Free Film-Forming Incontinence Skin Protectant. White Paper - 3M Healthcare, USA. 1999. Neonatal Skin Care: Guidelines for Practice. National Association of Neonatal Nurses, California;1997. Thomas S, Loveless P. A comparative study of the properties of twelve hydrocolloid dressings. World Wide Wounds. 1997;July. Available at: www.worldwidewounds.com. Accessed March 15, 2002. Bettley FR. Some effects of soap on the skin. Br Med J. 1960;1:1675. Pasche-Koo F, Piletta PA, Hunziker N, Hauser C. High sensitization rate to emulsifiers in patients with chronic leg ulcers. Contact Dermatitis. 1994;31(4):226–228. Fowler EM, Ouslander J, Paper J. Managing incontinence in the nursing home population. J Enterostomal Ther. 1990;(17):77–86. 36. Perez ED. Pressure ulcers: updated guidelines for treatment and prevention. Geriatrics. 1993;48(1):39–44. 37. Larsen PD, Martin JL. Polypharmacy and elderly patients. AORN J. 1999;69(3):619–622. 38. Fantl JA, Newman DK, Colling J, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 2: Urinary Incontinence in Adults: Update. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1996. AHCPR Publication No. 96-0682. 39. Krasner D. The chronic wound pain experience: a conceptual model. Ostomy/Wound Management. 1995;41(3):20–25. 40. Wells TJ. Managing falls, incontinence and cognitive impairment: nursing research. In: Funk SG, Tornquist EM, Champagne MT and Weisse RA, eds. Key Aspects to Elder Care: Managing Falls, Incontinence and Cognitive Impairment. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company;1992. 41. Davis D, Taylor A. Two decades of Dixon: the question(s) of evaluating continuing education in the health professions. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professionals. 1997;17:207–213. 42. Haynes B, Haines A. Getting research findings into practice. Barriers and bridges to evidence-based clinical practice. BMJ. 1998;317:273–276. 43. Beckman HB, Frankel RM. The effect of physician behaviour on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med. 1984;1010:692–696. 44. Price P. Health-related quality of life and the patient’s perspective. Journal of Wound Care. 1998;7(7):365–366. 45. Ovington L, Peirce B. Wound dressings: form, function, feasibility, and facts. In: Krasner D, Rodeheaver GT, Sibbald RG, eds. Chronic Wound Care: A Clinical Source Book for Healthcare Professionals, 3rd ed. Wayne, Pa.: HMP Communications;2001:311–319. 46. Panel for the Prediction and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 3: Pressure Ulcers in Adults: Prediction and Prevention. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1992. AHCPR Publication 92-0050. 47. Khachemourne A, Phillips TJ. Cost effectiveness in wound care. In: Krasner D, Rodeheaver GT, Sibbald RG, eds. Chronic Wound Care: A Clinical Source Book for Healthcare Professionals, 3rd ed. Wayne, Pa: HMP Communications; 2001:191–198. 48. Coutts P (2002) – personal communication June 2003 Vol. 49 Issue 6 41