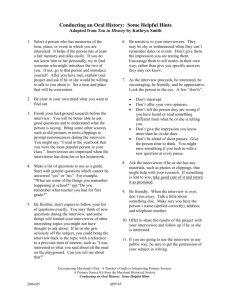

Learning Needs Analysis in Selected

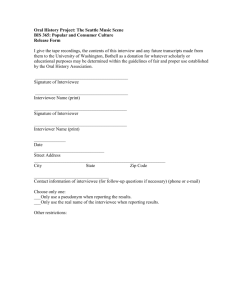

advertisement