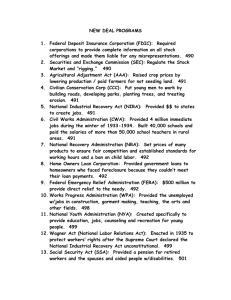

Tools of Government Workbook #5: Government Corporations and

advertisement