Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models

advertisement

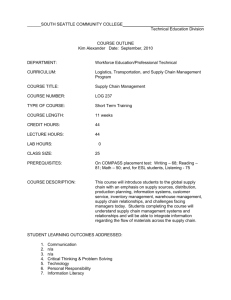

Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models Li-Yang Hsieh ,Hsiang-Sheng Lin Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models *1 Li-Yang Hsieh ,2 Hsiang-Sheng Lin Department of Transportation Technology and Logistics Management, Chung Hua University, Taiwan 707, Sec.2, WuFu Rd., Hsinchu, Taiwan 30012, hsieh.liyang05@gmail.com 2, Department of Transportation Technology and Logistics Management, Chung Hua University, Taiwan 707, Sec.2, WuFu Rd., Hsinchu, Taiwan 30012, keyman@chu.edu.tw *1, Corresponding Author Abstract In this study, we suggest a competency model for the Taiwanese logistics industry, for which a standard competency model has yet to be established. In this study, we examined the development status and personnel demand of the Taiwanese logistics industry. We referenced the competency model of the U.S. Employment and Training Administration (ETA) and held expert meetings to revise the U.S. competency content and suggest viable model content that is applicable to Taiwan. The results of this study can serve as references for aiding business managers in confirming the skills required from their industry professionals; for technical and vocational schools and training institutions in developing curricula and training modules based on competency; for the logistics industry in developing strategies; and for labor career planning. These results can also be referenced by government agencies when formulating development policies for the logistics industry. Keywords: Logistics Industry, Competency Model, Industry Professionals 1. Introduction Under the recent trend of globalization, many of Taiwanese companies have started to relocate, thus impacting the imports and exports of Taiwan to a certain degree. As the logistics market in Taiwan has become saturated with significantly declining market growth rates, many companies involved in the supply chain businesses have begun to leave Taiwan for the international markets. In the process, they have combined their production and marketing strategies with information systems and have taken the overall national development into consideration. Although there was an international financial crisis in 2008, the logistics industry in China still grew by 20%, with the express delivery market growing by more than 30%, because the Chinese government has pushed forward some policies to promote the construction of infrastructure and paid much attention to the logistics industry. Many Taiwanese logistics service providers have thus stepped into the China logistics industry to explore the business opportunities there. Because most of the Asia-Pacific economic geography is island, it must rely on water and air transportation to the resource flows between different countries. Therefore, industries relating "logistics" are very important in the Asia-Pacific economic region. Following the signing of the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) between Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), cross-strait trade relations have entered a normalization period. [1] Regional economic integration is an important global trend. Currently, nearly 247 free trade agreements exist worldwide, with the member countries sharing tariff exemptions. [2] Cities which are near the sea have become the most important zone in the world economic cycle. Within these cities-by-sea, it is the post that is most directly related to the world logistics system. Asked by the development of logistic economy, modern ports are net only the hubs of sea-land transportation, but also the distribution center of Advances in information Sciences and Service Sciences(AISS) Volume4, Number19, Oct 2012 doi: 10.4156/AISS.vol4.issue19.60 481 Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models Li-Yang Hsieh ,Hsiang-Sheng Lin international goods storage and distribution. The PRC is currently Taiwan’s primary export market; thus, a bilateral free trade agreement between Taiwan and the PRC benefits both countries. If the PRC successively signs agreements with other countries, it may enable Taiwan to integrate into the global trade system and attract multinational corporations to use Taiwan as a trade and investment platform to East Asia. The emergence of this trade trend and development opportunity is set to bring the operations of Taiwan’s logistics companies comprehensively into the internationalization era[3]. [4]This study proves the economic significance of logistics network. Meanwhile, it finds the interaction between the factors that influence the collaboration; there exist classification among the factors. These studies will promote the logistics networking. [5]Because of corporate internationalization, company demands for logistics professionals have become increasingly apparent. However, the domestic higher education system lacks a specialized academic department for training logistics personnel. Currently, personnel can only be recruited from related academic domains, such as international business, international trade, shipping and transportation management, transportation technology and logistics management, marketing and logistics, industrial engineering management, and business management, and then trained in logistics operations. Thus, [6] we referenced the competency models of advanced countries, organized discussions on the demand criteria of a competency model for Taiwan’s logistics industry, and proposed a competency model for Taiwan’s logistics industry professionals. [7]This model may serve as a reference for technical and vocational schools, institutions training logistics industry professionals, and students wishing to start a career in logistics. 2. Literature Review 2.1. Competency Model After Dr. David C. McClelland, [8] proposed the concept “competency” in 1973; “competency” has been broadly used in human resource management and development area. Such as recruitment within the organization, performance management, compensation and benefits, job training and development, career planning and succession planning, all of these are tightly connected with “competency”. Through the evaluation of personal competency and the design and development of the organization, we could build and construct Job training and development system of the competency model. Through this system, We could enhance the job performance of employees by improving their capabilities. Regarding domestic and foreign literature that explores the concept of competence, the earliest study to systemically define competency was [9]. In this study, “competence” was defined as “an underlying characteristic of an individual that is causally related to criterion-referenced effective and/or superior performance in a job or situation” [9]. Additionally, the following five competency characteristics were identified: 1. Motives: The things a person consistently considers or wants that causes action. 2. Traits: A person’s physical characteristics and consistent responses to situations or information. 3. Self-concept: A person’s attitudes, values, and/or self-image. 4. Knowledge: Information a person possesses of specific content areas. This knowledge enables a person to “perform/achieve” something. 5. Skill: A person’s ability to perform a certain physical or mental task. A number of these five competency characteristics can be classified as psychological, whereas others are more quantifiable. Therefore, [9] used the “Iceberg Model,” as shown in Fig. 1, to illustrate these five competency characteristics and their relationships with the definition of competency. 482 Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models Li-Yang Hsieh ,Hsiang-Sheng Lin Fig 1. Iceberg Model Source: Spencer and Spencer, “Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance”, 1993 2.2. U.S. industry Competency Model The U.S. industry competency model was a collaborative effort by the U.S. Department of Labor and the Employment and Training Administration (ETA), who invited industry, government, and academic sectors to construct a competency model that satisfied the industry’s needs. The completed model was then provided to business leaders, educators, economic developers, and public workforce investment professionals to use as a reference. This model can be adopted for the following applications: 1. To identify specific employer skill requirements. 2. Develop competence-based curricula and training models. 3. Develop industry-defined performance indicators, skill standards, and certifications. 4. Develop resources for career exploration and guidance. The competency model is divided into a pyramid with nine tiers. The arrangement of these tiers is not meant to imply a hierarchical ranking or suggest that those in the upper levels possess a higher level of competence. According to the form of this model, each level upward represents a greater degree of expertise and specialization required. Tiers 1 to 5 are separated into several blocks. Each block indicates a set of competencies, namely, the knowledge, skills, abilities, and necessary elements related to successful industry promotion. Tiers 1 to 3 are the foundational competencies. These foundations are the essential conditions for entering the workforce; Tiers 4 to 5 include the technical competencies specific to an industry and its sub-sectors; and Tiers 6 to 9 represent the necessary occupation-specific competencies. The U.S. industry competency model is shown in Fig. 2 [10]. 483 Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models Li-Yang Hsieh ,Hsiang-Sheng Lin Fig2. U.S. logistics industry competency model Source: http://www.careeronestop.org/competencymodel/pyramid.aspx 2.3. Taiwan’s Logistics Industry The logistics industries involving cross-border flows, there must be customs clearance, transportation, storage, distribution processing, information and other logistics services to cooperate each other. The U.S. Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals defines logistics as “the process of planning, implementing, and controlling procedures for the efficient and effective transportation and storage of goods including services, and related information from the point of origin to the point of consumption for the purpose of conforming to customer requirements.” The Taiwan Association of Logistics Management defined logistics as “logistics is the circulation of goods. During the circulation process, effective integration of transportation, warehousing, packaging, distribution processing, information, and other related logistics activities using management procedures creates value and satisfies customer and societal needs.” From a supply perspective, the logistics industry can be considered the supplier of logistics services; its primary business commodity is provision of professional logistics services to logistics consumers [11]. [12]The Taiwan Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DBGAS) placed Taiwan’s logistics industry under the jurisdiction 484 Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models Li-Yang Hsieh ,Hsiang-Sheng Lin of the “transportation and warehousing industry.” When the Standard Industrial Classification underwent its eighth revision in May 2006, the transportation and warehousing industry was defined as “any enterprise that uses any form of transportation method to provide regular or unscheduled transport of passengers or goods, and offers transportation support, warehousing operations, postal and courier services, including the hiring of transportation equipment operators.” The DGBAS’s summary of the transportation and warehousing industry and similar industries was subsequently classified into the following six categories: land transport, water transport, air transport, transportation support, mail and courier, and warehousing industries [13]. 3. Competency Model Structural Approach [9] proposes a simplified and easy method for implementing a competency model. This model primarily streamlines the work competency evaluation method. The process of selecting high-performing and standard-performing sample criteria is replaced with a panel of experts. The panel comprises experts from within and outside the organization, who determine the important competencies for a specific job or position by performing competency model analysis, searching for associated personnel, and engaging in collaborative discussions. This panel also identifies targets and performance indicators and distinguishes standard job competence from job competence that will lead to an outstanding performance. An additional survey analysis is used to determine the competency model for specific occupations. Finally, this model is cross-referenced with selected performance indicators. For this study, we gathered information of the manufacturing and business operations of Taiwan’s logistics industry. The content of practical competency model developed in this study for Taiwan’s logistics industry is presented in the following section. This model was based on the competency model proposed in [9], the results of a meeting, consultation, and survey of experts from Taiwan’s industry, government, and academic sectors, and the four applications and nine tiers of the U.S. industry competence model. 4. Results and Discussion 4.1. Tier 1: Logistics Industry Personal Effectiveness Competencies 1. Interpersonal skills: The ability to work with others from a range of backgrounds. 2. Integrity: Displaying acceptable social and work behavior. 3. Professionalism: Maintaining a professional demeanor. 4. Initiative: Demonstrating a willingness to work. 5. Dependability and reliability: Displaying responsible behaviors at work. 6. Adaptability and flexibility: Being open to change (positive or negative) and variety in the workplace. 7. Willingness to learn: Understanding the importance of learning new information for both current and future problem solving and decision making. 4.2. Tier 2: Logistics Academic Competencies 1. Reading: Understanding written words, paragraphs, and figures in work-related documents 2. Writing: Using standard language to compile information and prepare written documents. 3. Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: Applying basic scientific, technological, engineering, and mathematical principles to complete tasks. 4. Communication, visual and verbal: Listening, speech, and signaling so others can understand and communicating well enough to be understood by others. 5. Critical and analytical thinking: Possessing sufficient inductive and deductive reasoning ability to perform job successfully. 6. Basic computer skills: Using a computer and related applications to input, store, and retrieve information. 485 Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models Li-Yang Hsieh ,Hsiang-Sheng Lin 4.3. Tier 3: Logistics Industry Workplace Competencies 1. Teamwork: Cooperating with others to complete work assignments. 2. Customer focus: Efficiently and effectively addressing the needs of clients/customers. 3. Planning and organizing: Planning and prioritizing work to manage time effectively and accomplish assigned tasks. 4. Problem solving and decision making: Applying critical thinking skills to solve problems encountered at work. 5. Working with tools and technology: Selecting, using, and maintaining tools and technology to facilitate work. 6. Scheduling and coordinating: Making arrangements (e.g., for the transportation and distribution of goods) that satisfy all requirements as efficiently and economically as possible. 7. Checking, examining, and recording: Entering, transcribing, recording, storing, or maintaining information in written or electronic format. 8. Business fundamentals: Applying basic business and management principles to link industry trends with the services sold and provided by the company to the customer. 4.4. Tier 4: Logistics Industry-Wide Technical Competencies 1. Logistics, planning, and management: Planning, managing, and controlling the efficient and effective physical distribution of materials, products, and people to satisfy customers’ requirements. 2. Warehousing and distribution: Activities related to the operation of transportation and distribution facilities, including ports, terminals, and warehouses. 3. Transportation operations and maintenance: Activities related to the movement of people, materials, and products by road and/or rail. 4. Technology applications: Maintaining an awareness of technological advances and applying appropriate technology to transportation, distribution, and logistics processes. 5. Regulations and quality assurance: Comply with relevant local and international laws and regulations that influence the transportation, distribution, and logistics industry, applying industry standards to ensure service quality. 6. Customer relationship management: Marketing/selling transportation services and providing customer service to transportation service consumers. 7. Health, safety, and the environment: Assessing and managing risks associated with safety and environmental issues. 4.5. Tier 5: Logistics Industry Sector Technical Competencies 1. Laws and regulations: Understanding central government and local laws and regulations regarding logistics. 2. Health and safety: Understanding and managing logistics health and safety laws. 3. Standard logistics operation: Understanding logistics business and organization structure and operation scope, providing logistics services and functions. 4. Customer service: Awareness of the correct arrival time of customer goods and a comprehensive understanding of the geography and route. 4.6. Tier 6: Logistics Industry Occupation-Specific Knowledge Competencies Possess knowledge relevant to the logistics industry, such as knowledge on strategic planning, human resources modeling, leadership skills, production methods, personnel and resource coordination, and management principles. 486 Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models Li-Yang Hsieh ,Hsiang-Sheng Lin 4.7. Tier 7: Logistics Industry Occupation-Specific Technical Competencies Possess specialized materials science, logistics equipment, and consumer goods knowledge, including storage/handling skills. 4.8. Tier 8: Logistics Industry Occupation-Specific Requirements Possess knowledge of foreign languages, including relevant vocabulary, speaking, reading, and writing competency, economics, mathematics, statistics, commercial law, government regulations, procedures, decrees, and proxy rules. 4.9. Tier 9: Logistics Industry Management Competencies Logistics industry management competencies, such as monitoring and controlling resources, preparing and evaluating budgets, staffing, managing conflict and team building, crisis management, monitoring work, delegating work, developing and mentoring, developing an organizational vision, strategic planning, and implementation. 5. Conclusion In this study, we developed a competency model for Taiwan’s logistic industry professionals, providing a reference for technical and vocational schools, personnel training institutions, and students wishing to start a career in logistics[14]. The competency model for logistics industry professionals constructed in this study was divided into “professional training provided in school or training institutions” and “logistic career hopefuls in training,” as explained below. 5.1. Professional Training in School or at Training Institutions During the professional training process in school or at training institutions, the holistic clarity, connectivity, systemization, and implementation ability of the course curricula must be ensured; the course design, competence application, and goal requirements must be integrated; planned curricula must be implemented; advice or assistance on transferring learning outcomes must be provided; and the diversity and integrity of competence results must be regularly assessed, checked, and analyzed. 5.2. Logistic Career Hopefuls in Training Logistic hopefuls in training must understand and pay attention to the framework, function, and positioning of the competency model for logistic industry professionals. They must further acknowledge that the cultivation of competency for the logistics industry is not a fad; instead, it requires time, perseverance, patience, and a good learning attitude and motivation. 6. References [1]Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement, May 2012 Information on http://www.ecfa.org.tw/,2011 [2]Li-zhuo Liu, “The Forecast of Qinhuangdao Logistic based on BP Neural Network”, JDCTA, Vol. 6, No. 8, pp. 8 ~ 16, 2012 [3]Li-Yang Hsieh, Hsiang-Sheng Lin, “Strategy of Collaborative Logistics Talent Training in ECFA Era”, 12th China Association for Science and Technology Annual Meeting Thesis, Fuzhou China, Fuzhou University, 2010. [4] Jia-ji Hu, Wen-liang Bian, Shu-yi Han, Song-dong Ju, “An Empirical Research of the Influence Factors of the Action from MF Network Collaboration to Logistics Organization Performance”, AISS, Vol. 3, No. 6, pp. 259 ~ 265, 2011 487 Taiwan Logistics Industry Competency Models Li-Yang Hsieh ,Hsiang-Sheng Lin [5]Hsiang-Sheng Lin, Li-Yang Hsieh, “Strategy of International Logistics Talent Training in ECFA Era”, Material Handling Magazine & Modern Logistics, Vol.48, pp.44~48, 2010 [6] Ministry of Economic Affairs industry competency, Functions of the Ministry of Economic Affairs industry competency List, May2012Informationon on http://hrd.college.itri.org.tw/Competency/, 2012 [7]Transportation Competency Model, May2012Information on http://hrd.college.itri.org.tw/Competency/index_form.asp?id=UC11, 2011 [8] McClelland, D. C, “Testing for competence rather than for intelligence”, American Psychologist, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp.1~24, 1973 [9] Spencer, L.M. & Spencer, S.M, Competence at Work: Models for superior performance, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York, U.S., 1993 [10] U.S. Industry Competency Model: U.S. Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration (ETA), May2012 Information on http://www.careeronestop.org/competencymodel/pyramid.aspx [11]Taiwan Association of Logistics Management. Logistics Interpretation. May 2012 Information on http://www.talm.org.tw/, 1996 [12] Taiwan Logistics Yearbook, 2009 Taiwan Logistics Yearbook, Taipei City: Ministry of Economic Affairs, Commerce Industrial Services, R.O.C., 2009 [13] Transportation and Storage Industry, Standard Industrial Classification, May 2012 Information on http://www.stat.gov.tw/lp.asp?CtNode=1309&CtUnit=566&BaseDSD=7, 2006 [14] Ping Gong, Shi Zhang, “FDR-based Compositional Verification for OWL-S Process Model”, JCIT, Vol. 7, No. 12, pp. 398 ~ 409, 2012 488