Class Three Materials

advertisement

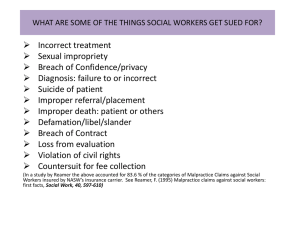

Class Three Materials Professor McGinley Reading Materials for Class 3 University of Insubria, Como Italy American Tort Law Materials for Class 3: Special Problems in Negligence: Medical Malpractice and Health Care Reform (Please read before class and be prepared to discuss). III. Medical Malpractice A. Standard of Care In order to prove medical or other professional malpractice, the plaintiff must establish what the standard of care is. The standard of care is the duty to the patient. A breach of this duty is negligence. If the patient can prove that the breach of the duty was an actual and proximate cause of the plaintiff’s injuries, the plaintiff will prevail. Ordinarily, the standard of care is established through an expert who testifies what a reasonable physician under the circumstances would do. Different standards exist in American courts. The locality rule adopts the standard of care of physicians in the local area. This standard is problematic because it is difficult in a small town to find doctors willing to testify and the local doctors are arguably the only ones qualified to testify. The modified locality rule solves this problem by looking at the standard of care of doctors in similarly sized cities or towns. But there is still a problem of a “race to the bottom.” . Because of increased and improved communications between cities and rural areas and the prevalence of technology in all places, courts have moved to a national standard of care. Of course, if the particular locality where the alleged malpractice occurred did not have the same access to up-to-date technology, that fact would be taken into account in determining the standard of care. Usually doctors will be held to the standard of care of a physician with that physician’s specialty or expertise. Of course, a doctor without expertise in a particular area (a general practitioner) may be negligent if that doctor does not refer the patient to someone with specialized expertise. B. Expert Testimony The following statute codifies in part a common law doctrine called res ipsa loquitur. Res ipsa loquitur is a doctrine that provides that in some situations the plaintiff does not have to establish negligence by expert medical testimony because the “act speaks for itself.” In other words, it is obvious that there was negligence and it would be unjust for the plaintiffs to have to prove negligence. It began in medical malpractice cases in situations where the plaintiff could not testify because the plaintiff was unconscious due to anesthesia. The courts did not want to permit doctors to refuse to speak and therefore to escape liability. Nevada has codified this doctrine, but has also limited it in the following statute. 1 N.R.S. 41A.100 [N.R.S. stands for “Nevada Revised Statutes.” These are statutes that apply to the state of Nevada]. 41A.100. Required evidence; exceptions; rebuttable presumption of negligence 1. Liability for personal injury or death is not imposed upon any provider of medical care based on alleged negligence in the performance of that care unless evidence consisting of expert medical testimony, material from recognized medical texts or treatises or the regulations of the licensed medical facility wherein the alleged negligence occurred is presented to demonstrate the alleged deviation from the accepted standard of care in the specific circumstances of the case and to prove causation of the alleged personal injury or death, except that such evidence is not required and a rebuttable presumption that the personal injury or death was caused by negligence arises where evidence is presented that the personal injury or death occurred in any one or more of the following circumstances: (a) A foreign substance other than medication or a prosthetic device was unintentionally left within the body of a patient following surgery; (b) An explosion or fire originating in a substance used in treatment occurred in the course of treatment; (c) An unintended burn caused by heat, radiation or chemicals was suffered in the course of medical care; (d) An injury was suffered during the course of treatment to a part of the body not directly involved in the treatment or proximate thereto; or (e) A surgical procedure was performed on the wrong patient or the wrong organ, limb or part of a patient's body. 2. Expert medical testimony provided pursuant to subsection 1 may only be given by a provider of medical care who practices or has practiced in an area that is substantially similar to the type of practice engaged in at the time of the alleged negligence. 3. As used in this section, "provider of medical care" means a physician, dentist, registered nurse or a licensed hospital as the employer of any such person. *** [Following is a media description of a terrible event happening during an operation to put in a pacemaker. Consider whether the above statute would be applicable in this case]. 2 3 4 5 C. Policy Supporting Medical Malpractice The policy behind medical malpractice is to compensate victims and to deter negligent behavior. Courts often talk about the need to encourage more careful behavior and the need to reform how professionals behave is a central theme in medical malpractice litigation. An important question is whether the law is actually encouraging and causing the types of behaviors it hopes to encourage. Doctors often criticize the law and argue that it encourages decisions that lead to very high costs – needless tests, etc. Consider these issues when you read the policy section below. D. Informed Consent The following case illustrates how the courts analyze the informed consent doctrine, a doctrine that holds a physician liable for malpractice even if the medical service was not performed negligently if the doctor fails to inform the patient of the potential risks of the procedure and to get the patient’s consent. LINDSAY SMITH, M.D., Appellant, v. JAMES JEFFREY COTTER and BONNIE ELIZABETH COTTER, Respondents No. 20913 Supreme Court of Nevada 107 Nev. 267; 810 P.2d 1204; 1991 Nev. LEXIS 45 April 30, 1991 April 30, 1991, Filed JUDGES: Mowbray, C. J., Springer, J., Rose, J., Steffen, J., Young, J. OPINION BY: PER CURIAM OPINION This is a medical malpractice action. After a bench trial, the district court awarded damages against Dr. Lindsay Smith because of his negligent failure to obtain James Cotter's informed consent to a surgical operation, a total thyroidectomy. Cotter claims that Dr. Smith failed to inform him that he could suffer paralyzed vocal cords and an obstructed airway as a complication of the surgery. Dr. Smith claims that he told Cotter of the risk and that, even if he did not, he was not required by professional standards to tell Cotter of this risk. There is ample evidence to support the trial court's conclusion that Dr. Smith failed to inform Cotter of the risk, that he should have done so, and that this failure was the cause of Cotter's injuries. We therefore affirm the judgment of the trial court. 6 Cotter suffered thyroid problems for several years. On January 16, 1985, Mr. and Mrs. Cotter met with Dr. Smith. Dr. Smith noted in his office chart that he had discussed some of the complications associated with a total thyroidectomy namely, "infection, bleeding, recurrent laryngeal nerves and parathyroids." The trial judge concluded that neither Mr. nor Mrs. Cotter came away from that meeting with any idea that there was a risk of "total vocal cord paralysis, or permanent voice impairment or permanent airway obstruction." Cotter elected to have surgery, and he was operated on, on January 21, 1985. Following the surgery, Cotter was referred to a larynx expert, Dr. Dedo, who concluded that during surgery Cotter sustained an insult to the bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve resulting in paralysis. The district court concluded from the medical evidence that Cotter could not close his vocal cords to the degree required for normal speech nor could he open his vocal cords to the degree required for normal breathing. The district court found that Cotter has suffered a permanent disability as a result of paralyzed vocal cords, an obstructed airway and placement of the tracheotomy tube. Based upon these findings of fact the district court found that Dr. Smith failed to obtain Cotter's informed consent to a total thyroidectomy. The court found that the standard of care for a board certified general surgeon requires the surgeon to inform the patient of the risks of surgical injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and of permanent vocal cord paralysis and airway obstruction. There is ample evidence to support these findings. The only expert who testified on behalf of the Cotters on the issue of informed consent was Dr. Knoernschild. When asked his opinion, "based upon reasonable medical probability," as to the proper information to be given by a general board certified surgeon preparing to perform a thyroidectomy, Dr. Knoernschild testified that he "thinks" that the surgeon should "inform the patient of the most hazardous complication of a thyroidectomy: that is, the division of one or both of the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the bilateral vocal cord paralysis or chronology." Based upon the question he was responding to, the testimony was reasonably taken by the trial court as an expert opinion on what the standard of care is for a general surgeon performing a total thyroidectomy. Dr. Smith's own records presented at trial indicate that he informed Cotter of various risks ("bleeding, infection, recurrent laryngeal nerve and parathyroid"), but no mention is made of vocal cord paralysis or impaired breathing. Dr. Smith testified that the implication of the note regarding recurrent laryngeal nerve "has to include vocal cord paralysis." He went on to state specifically that vocal cord paralysis was discussed. Mr. Cotter on the other hand testified that prior to surgery Dr. Smith never mentioned the risk of permanently paralyzed vocal cords. Although conflicting evidence was presented with respect to the information given by Dr. Smith, there was sufficient evidence to support the trial court's finding that the doctor failed to inform Cotter of the risk of vocal cord paralysis. The trier of fact was in the best position to sort through the conflicting evidence, and its finding on this issue should not be disturbed. Dr. Smith also contends that the element of proximate cause has not been established in this case. To establish proximate cause, first there must be a showing that the unrevealed risk which should have been revealed by the doctor actually materialized. In the instant case, the unrevealed risk was the risk of vocal cord paralysis and the consequent voice loss and breathing impairment. Although there is conflicting evidence, the district court found that Cotter's vocal cords were 7 paralyzed. Accepting this finding of fact based upon conflicting evidence, the initial requirement for proving proximate cause is fulfilled. Additionally, it must be shown that Cotter would have refused the surgery if he had been informed of the risk of permanent vocal cord paralysis. The plaintiff's assertion that he or she would have refused the treatment must be reasonable under the circumstances. In determining reasonableness, the court may consider the testimony of the patient as well as medical evidence regarding the risks of remaining untreated, the possible alternative treatments and the risks and expected benefits of alternative treatments. Credible evidence was presented at trial to support the trial court's conclusion that Mr. Cotter would not have undergone the thyroidectomy if he had known of the risk of permanent vocal cord paralysis. Cotter testified that if he had been told of the risk of permanent vocal cord paralysis he would not have elected to have the surgery. This evidence is not conclusive, but it can be considered by the fact-finder. Evidence was also presented at trial that Cotter's thyroid problem was only a minor irritant and that it only required medical attention every few months. Further, an abundance of expert testimony (although at times conflicting) was presented on the issue of the risks of a total thyroidectomy. Alternative treatments were addressed somewhat by Dr. Knoernschild who testified that a subtotal thyroidectomy would have created less of a risk of vocal cord paralysis. Also, there was some evidence regarding Cotter's prior treatment and certainly the continuance of that treatment could have been seen as an alternative by the lower court. We conclude that the trial court did not err in finding that the evidence supported the required element of proximate cause in this case. We affirm the judgment of the district court. Question: Was there a jury in the Smith case? How do you know? *** E. The Rising Costs of Health Care: Policy Considerations Below is a sample of news articles and opinion pieces written about the rising cost of health care and its alleged link to medical malpractice litigation. Copyright 2010 The New York Times Company The New York Times February 22, 2010 Monday Late Edition - Final SECTION: Section A; Column 0; Editorial Desk; OP-ED CONTRIBUTOR; Pg. 19 LENGTH: 293 words HEADLINE: How the G.O.P. Can Fix Health Care BYLINE: By NEWT GINGRICH. 8 NEWT GINGRICH, former speaker of the House of Representatives and founder of the Center for Health Transformation, a health-care policy consulting firm BODY: CAT scans, blood tests, ultrasounds, Caesarean sections -- in many instances, these diagnostic tools and procedures are vital for treating patients. Too often, however, such procedures are ordered unnecessarily and drive up the cost of medicine for patients, taxpayers and insurance carriers. A new Gallup poll, commissioned by Jackson Healthcare, indicates that doctors believe an astounding one in four health care dollars is now spent on unnecessary care. Doctors order these procedures to protect against frivolous suits filed by trial lawyers seeking an easy payout, particularly after a doctor makes a simple mistake. Seventy-three percent of the doctors surveyed said they had practiced defensive medicine in the past year. As a result, American patients not only endure extra hours of tests and treatments but also pay more for health care. If President Obama and Congress are serious about reducing health care costs, then the more than $600 billion a year in unnecessary care should be at the top of the list. Congress must give states the incentive to reform their civil justice systems so that lawyers will think twice before suing doctors for frivolous cases. There is a place for health courts that address only medical malpractice cases, and a need for caps on damages for ''pain and suffering'' that have nothing to do with lost wages or actual damages. Doctors who incorporate best medical practices should be protected from lawsuits altogether. These reforms would allow doctors to stop playing defense, and make it possible for patients and taxpayers to better afford health care. Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company The New York Times March 10, 2005 Thursday Late Edition - Final SECTION: Section A; Column 1; Editorial Desk; Pg. 27 LENGTH: 436 words HEADLINE: False Diagnosis BYLINE: By Bernard Black, Charles Silver, David Hyman and William Sage. Bernard Black and Charles Silver are law professors at the University of Texas at Austin. David Hyman is a professor of law and medicine at the University of Illinois. William Sage is a law professor at Columbia. DATELINE: Austin, Tex. 9 BODY: MEDICAL malpractice litigation reform is a high priority for President Bush, who contends that juries are running amok, multimillion-dollar settlements are on the rise and greedy trial lawyers are filing frivolous suits. The results, Mr. Bush and others argue, include skyrocketing insurance prices, abandoned medical practices, defensive medicine and a crisis of access to care. Their proposed solution: caps on jury awards to patients and on lawyers' contingent fees. No one disputes that insurance premiums have risen significantly. The question is whether a crisis in states' tort systems accounts for the increase. Consider Mr. Bush's home state of Texas, America's second most populous state and the third largest in terms of total health care spending. After studying a database maintained by the Texas Department of Insurance that contains all insured malpractice claims resolved between 1988 and 2002, we saw no evidence of a tort crisis. Adjusting for inflation and rising population, we arrived at the following findings: Large claims (with payouts of at least $25,000 in 1988 dollars) were roughly constant in frequency. The percentage of claims with payments of more than $1 million remained steady at about 6 percent of all large claims. The number of total paid claims per 100 practicing physicians per year fell to fewer than five in 2002 from greater than six in 1990-92. Mean and median payouts per large paid claim were roughly constant. Jury verdicts in favor of plaintiffs showed no trend over time. The total cost of large malpractice claims was both stable and a small fraction (less than 1 percent) of total health care expenditures in Texas. In short, as far as medical malpractice cases are concerned, for 15 years the Texas tort system has been remarkably stable. Texas's situation is not unique. One study of Florida's experience from 1990 to 2003 also found declines in paid claims per 100 practicing physicians as well as per 100,000 population. Over the same period in Missouri, the total number of malpractice claims fell by about 40 percent and the number of paid claims dropped almost by half. Malpractice premiums have risen sharply in Texas and many other states. But, at least in Texas, the sharp spikes in insurance prices reflect forces operating outside the tort system. The medical malpractice system has many problems, but a crisis in claims, payouts and jury verdicts is not among them. Thus, the federal ''solution'' that Mr. Bush proposes is both overbroad and directed at the wrong problem. *** Limiting non-economic damages in Medical Malpractice cases The following statute was passed by Nevada citizens in response to a petition that was put on the ballot. It limits non-economic damages in medical malpractice cases. This resulted from a very political debate in which many including President Bush and the American Medical Association took the position that there was a litigation explosion that was a primary cause of 10 rising health care costs. There was concern that medical doctors would leave the state because they were having trouble getting reasonable medical malpractice insurance. Nev. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 41A.035 (2009) 41A.035. Limitation on amount of award for noneconomic damages. In an action for injury or death against a provider of health care based upon professional negligence, the injured plaintiff may recover noneconomic damages, but the amount of noneconomic damages awarded in such an action must not exceed $350,000. HISTORY: 2004 initiative petition, Ballot Question No. 3. Effective date. This section is effective November 23, 2004. Questions 1. What are non-economic damages? What are economic damages? 2. Are any particular groups of plaintiffs harmed more by the restriction on noneconomic damages? Key Terminology Standard of care Medical malpractice Res ipsa loquitur Rebuttable presumption Compensate victims Deter negligent behavior District court Informed consent Conflicting evidence Credible evidence 11