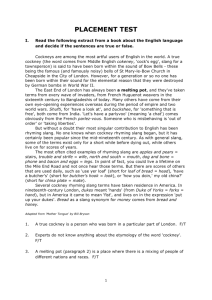

Some Linguistic Aspects of Cockney Dialect and Rhyming Slang

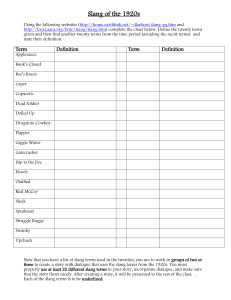

advertisement