Sample Two - Scholars Online

advertisement

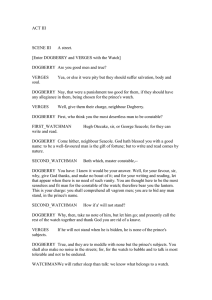

Positioning the Cohorts Structure & Outlining Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart could write a musical piece entirely out of his head—that is, he would mentally compose the entire tune, complete with orchestration, harmony, and so forth, and then write it down, note-­‐perfect. He didn’t need to make rough drafts, or make any adjustments. It must have been astonishing to watch. But Mozart was a born genius. Every other composer has had to go about it more like Beethoven: through slow and careful drafting, with many revisions. Writing words and writing music are not that different in this regard. If you are the Mozart equivalent of essayists or novelists, you don’t need outlines, and you’ll have your structure mapped out already. For the rest of us, however, structure is something that needs to be examined closely, and outlines are not just useful—they are essential. Structure A well-­‐structured piece of writing uses the order of the ideas being presented to augment those ideas—essentially, using the way the ideas are put together to add to their weight and effectiveness. The order of the ideas should follow some logic; otherwise the essay will be disorganized, scattered, and confusing. Here’s an example of fairly scattershot organization: Don Pedro: Officers, what offense have these men done? Dogberry: Marry, sir, they have committed false report; moreover, they have spoken untruths; secondarily, they are slanders; sixth and lastly, they have belied a lady; thirdly, they have verified unjust things; and, to conclude, they are lying knaves. (Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing, Act V Scene I) Obviously Dogberry has problems with basic numbering; but beyond that, he has really only brought one charge against Conrade and Borachio, not six, namely lying. Admittedly there are different types of lying going on, but because Dogberry’s organization is fairly poor, he’s multiplied the charges considerably. As a result, he looks fairly idiotic, and his accusations, however truthful, are nearly ignored simply because he’s presented them poorly. A rather superior form of structure can be found in Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address [link]. Lincoln explains what he will not be speaking about, and why; then he proceeds to explain the American Civil War in several ways, ascending from political and economic causes to moral and spiritual ones. In doing so he constructs his own case that the Civil War was a just punishment for the United States due to the sin of slavery. His famous conclusion (“With malice toward none, with charity for all...”) springs directly from the moral argument he has just laid out. Each piece of the speech flows naturally from the piece before it; each piece of the speech is of greater weight and importance that what came before it. Written Copyright 2014 by Bruce A. McMenomy & Paul Christiansen. Do not redistribute. at the height of the president’s prowess with words, it’s a masterpiece of careful structure reinforcing a point or message. Types of Structures There are quite a few different types of structures. The following is not a complete list, but it does cover most of the main ways to organize your thoughts. Chronological Spatial Order of importance Descending Ascending Order of effectiveness Ascending Descending Thematic Chronological: This simply means ordering your points in the order they occurred. This is best done for narrative, be it fiction or non-­‐fiction. It has the advantage of being extremely easy to plan, as history has done the mapping-­‐out for you. This kind of ordering is also ideal for writing cause-­‐and-­‐effect pieces, as the cause must naturally precede the effect. However, chronological order has certain weaknesses, a primary one being that events don’t usually come in any kind of logical or aesthetically sound order. In other words, if you organize your piece according to strict chronology, it may still seem disorganized, because life is disorganized. (Cause-­‐and-­‐effect pieces are an exception.) Spatial: This type of ordering relies on how things are arranged physically in space (hence “spatial”). Though best used for descriptions, spatial order can sometimes be an interesting way of laying out a narrative. It’s hard to transfer spatial order to abstract concepts, however, so this time of structure is a poor choice for persuasive or argumentative writing. Order of Importance: A true classic, the order of importance lays out facts, opinions, reasons, or what have you according to how much they matter. In descending order, you present the points that matter most up front, and the lesser points last; in ascending, your present your more trivial points to begin with, and then build up to the most essential point you wish to make at the end. Lincoln’s Second Inaugural used the ascending approach, by beginning with the immediate human causes of the conflict, then expanding his argument to divine judgment. The natural question is, “Should I use ascending or descending?” There are different schools of thought. Some say you should begin with your most crucial topics, to catch the reader’s attention at once; others feel that you should build up to the most crucial at the end, as that is what will linger in your reader’s mind. If you have reason to believe that your reader will lose interest quickly, you might want to begin strong; if you have confidence they will stick around, you can end strong instead. But perhaps a compromise approach of putting the more trivial stuff in the middle might help. Copyright 2014 by Bruce A. McMenomy & Paul Christiansen. Do not redistribute. Order of Effectiveness: Quite similar to order of importance, this kind of structure is most relevant in writing where you want to create a specific and deliberate effect on your reader. If you want to persuade your audience to change their minds and adopt your opinion, you might want to lay out your most persuasive arguments in ascending or descending order; if you want your reader to feel a particular emotion, you might use your most effective imagery in ascending order to create a powerful emotional climax. Like order of importance, you can write in ascending or descending order according to the kind of piece you want to create, or according to your audience, and again, there are different schools of thought about which is better. It’s up to you, and again, you may want to adopt a hybrid approach. Returning to our example of Lincoln’s speech, we see that Lincoln uses order of effectiveness here as well, with his audience in mind. Today’s political crowds might not automatically welcome a Bible-­‐based approach, but Lincoln moves from the everyday to the scriptural, ascending in importance as he does. He also crafts his imagery in ascending order of effectiveness as well. To begin with his phrases are plain, though well-­‐balanced (“...All thoughts were anxiously addressed to an impeding civil war. All dreaded it—all sought to avert it...”). Later in the speech, his language and imagery, while still relying on balanced phrases, are far more vivid (“...Until every drop of blood drawn by the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword...”). Thematic: this form of ordering places similar points together—similar in terms of how they relate to each other. A thorough description of a house might put all the descriptions of colors together in one paragraph, and place that next to a paragraph about geometry and angles of light—connecting them all because they are visual elements. Then the author might proceed to pleasing smells and sounds of the house, putting all the aesthetic items together. And so forth. To show you the difference between good and bad structure, and just for fun, here’s Dogberry’s poor presentation again: Dogberry: Marry, sir, they have committed false report; moreover, they have spoken untruths; secondarily, they are slanders; sixth and lastly, they have belied a lady; thirdly, they have verified unjust things; and, to conclude, they are lying knaves. (still Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing, Act V Scene I) ...and here’s a reorganized form of his charges, arranged thematically and in ascending order of importance and effectiveness: Dogberry: Marry, sir, they have spoken untruths; secondly and specifically, they are slanders, for thirdly, they have belied a lady; fourthly, they have verified unjust things to an officer at law; to conclude, they are lying knaves. “Spoken untruths” lays out the general category of the crimes, that is, lying; “they are slanders, for they have belied a lady” zeroes in on the particular kind of lie; “they have verified unjust things to an officer” compounds the problem, for this Copyright 2014 by Bruce A. McMenomy & Paul Christiansen. Do not redistribute. shows the culprits have perjured themselves (that is, they’ve lied to the court) about their prior lies; finally, “they are lying knaves” brings us back full circle, but with much more forceful language. Outlining Outlines are essential tools for mapping out what you intend to write. In outline form it’s easy to examine your structure, and adjust it if need be. A good outline also serves as your guide to what you intend to write next, so you never need to pause to decide what should follow what you’ve just written. I (Mr. C) have been writing for school and for pleasure for about two decades now, and I can assure you that I can get almost nothing done without an outline. For example, in preparing to write the “Structure” section you’ve just read, I wrote out the list of types of structure first, and used that as my outline. There are a number of arbitrary rules involved in old-­‐school outlining, and we aren’t going to bother with most of them. For example, classically, an outline was to contain no verbs. Frankly, I don’t care whether it does or not. Likewise, it doesn’t matter how many spaces you indent, so long as you’re consistent throughout—I personally just use the Tab key. On the other hand, it was conventional that an outline should never have just one sub-­‐heading under a given header. That is, there should be no A without at least a B, no 1 without a 2, and so forth. There is a good reason for this. The point of the outline is to break the subject down into parts, and to break those down further. If you break something down into only one part, you aren’t breaking it down at all. (If you’re only dividing by one, in other words, you might as well not write the denominator; to put it yet another way, Dogberry’s speech as Shakespeare wrote it would have had a lot of As without Bs.) So while we’re somewhat flexible in this class, use the form and the pattern of numbering shown below, since it’s conventional and well-­‐understood. The important point about an outline is that it should serve as a clear indication of the organization of the content of your essay. Each main point should be clearly related to the thesis of the essay, and each subordinate point should support the main point that is the next step up in the hierarchy. Don’t write a procedural outline, which is really only a note on the structure of your paper and how you’re going to write it. It’s not grappling with the material you’ve set out to write about. That’s what you need to be doing. Here’s a procedural outline: Thesis statement. I. Introduction A. Define terms B. Thesis statement II. First point A. Definition B. Example III. Second point Copyright 2014 by Bruce A. McMenomy & Paul Christiansen. Do not redistribute. A. Definition B. Example IV. Conclusion What’s wrong with it? Nothing, as a description of the process—but you don’t want a description of the process. You want the skeleton of your actual paper. This kind of outline, charming and generic as it is, really doesn’t say anything about the subject of the essay. This could be an outline about biochemistry, historical fiction, or music theory. When you write an outline for a class, you want to prepare your material for orderly delivery. It’s not just about having the crates on the shipping dock: there has to be something in the crates as well. Compare the substance outline: Different errors in sentence structure confuse readers. I. Faulty sentence structure presents various forms. A. Too many ideas crowd into run-­‐on sentences B. Incomplete ideas presented as fragments II. Run-­‐on sentences A. Basic types 1. Spliced sentences 2. Fused sentences B. Ways to fix run-­‐on sentences 1. Split into two or more sentences 2. Separate with colon or semicolon 3. Separate with comma and coordinating conjunction III. Fragmentary sentences A. Phrases and clauses that cannot stand on their own 1. Subordinate clauses 2. Participial phrases 3. Infinitive phrases 4. Prepositional phrases B. Ways to fix fragmentary sentences. 1. Check for subject 2. Check for main verb 3. Fold dependent structures in with a main clause IV. Clarity of expression depends on complete, discrete thoughts A. Ensuring proper sentence structure depends on completeness of thought 1. Look for problems 2. Identify types of problem 3. Fix problem B. Results are more comprehensible and convincing essays. Those who are familiar with the song “The Title of the Song” will readily appreciate the difference between the procedural outline and the content outline. There is another use for outlines: analysis and assessment. Making an outline of a text can be a useful way of understanding the material, or of taking notes on it; Copyright 2014 by Bruce A. McMenomy & Paul Christiansen. Do not redistribute. you can also make an outline of something you yourself have written (even if you started from an outline to begin with, so long as you don’t look at your original version) to figure out its strengths and weaknesses. This is a less-­‐common use, and we won’t require you to do that for the Cursus, but it’s occasionally a useful trick to know and employ. Assignments Assignment One Select three topics from the following list of possibilities. Write an outline for each one. Use a specific type of structure, and write a paragraph below your outline explaining which structure you used, why you chose that type, and why your outline fits your chosen structure. Be sure to hand in both parts, the outline and the explanatory paragraph, in one file. What is a hero? The examples you use may come from your personal experience, literature, history, current events, or the popular media. Compare and contrast your most favorite and least favorite foods, explaining why you like or dislike each dish. The most important personal trait to have is ______________ (make your own choice; you could chose charity, faith, integrity, honesty, etc.) [Or, choose a subject from one of your other classes.] Assignment Two Read one of the 20th-­‐CenturyAmerican speeches at the link—your choice. You may certainly pick one of the shorter ones. Summarize the speech briefly in one paragraph. In a second paragraph (or more than one), state what kind of structure or structures the speechwriter has used. Explain your reasoning carefully, using citations from the text. If you find that creating an outline of the speech would be useful, feel free to do so for extra denarii. Assignment Three (Not to be attempted by the faint of heart.) Read the dialogue between the Man in Black and Vizzini, from The Princess Bride. Attempt to determine what structure, if any, Vizzini employs in the course of his argument. Write a paragraph explaining your conclusion, being sure to cite specific sections of the text to support your opinion. Copyright 2014 by Bruce A. McMenomy & Paul Christiansen. Do not redistribute. Copyright 2014 by Bruce A. McMenomy & Paul Christiansen. Do not redistribute.