Effective Revision Techniques

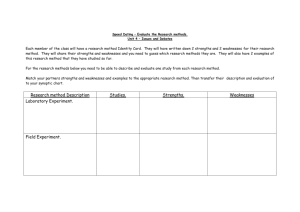

advertisement

REVISION SUGGESTIONS Make sure your revision is effective All of these ideas are better if you do them out loud. Most of them are also better if you can do them with a partner – they don’t necessarily need to be a psychologist – a willing person can read questions out! Working with someone else is excellent, but it is even more important that your revision is your own. This isn’t anything to do with cheating, it’s simply that you will remember much better if you planned or wrote (or collaborated on) something yourself than if it was exclusively someone else’s work. Know the exam injunctions – the key words that are used in questions (eg outline, discuss, evaluate, assess, criticise, compare etc). Making good notes and summarising Yes, there really is no way round it: you have to write revision notes. There are three reasons for this. practice: the more times you use encounter the same ideas, the better you will remember them deep processing: by summarising your notes, or organising them differently, you are having to think about the ideas, which means you will understand them better and be more likely to remember them minimal cues: by reducing your notes each time you summarise a topic, you are narrowing down the cues you need to access your memory. This helps with the ultimate aim, ie for the few key words in an exam question to trigger your recall for all the detail about that topic. Tabulate A good way to summarise your notes is to tabulate them. You can use this technique whenever you can make comparisons or put things into a sequence. For example: stages: Freud’s psychosexual theory; the Oedipus complex, the Electra complex, the biology of gender development, how classical conditioning works, steps in Ainsworth’s strange situation. strengths and weaknesses: of studies; theories; research methods; experimental designs. In each case, see if you can make the rows ‘line up’ eg if you are identifying a strength of a study in terms of validity, does it also have weaknesses in terms of validity (though bear in mind that won’t always be possible). When evaluating studies remember: o Generalisibility o Reliability o Application o Validity o Ethics When evaluating theories remember: o Strengths o Weaknesses o Evidence o Alternative explanations o Relevance to Real life similarities and differences: although questions asking for comparisons (similarities) and contrasts (differences) are relatively uncommon, they could be asked. More importantly, this exercise helps you to understand key aspects of concepts. Illustrate and annotate Although few topics in psychology require you to ‘learn a diagram’ (perhaps just Freud’s ‘iceberg’ model and the structure of a neuron and synapse) many aspects of psychology can be illustrated. A simple example is using sketches to help you to remember researcher’s names – though remember, it’s always more important to know what they did and found and what it means. Some concepts can also be represented in diagrams. For example, in cognitive psychology, the multi-store model and the working memory model can be represented diagramatically. In developmental psychology the Oedipus and Electra complexes can be illustrated, as can fixation at different stages of development. In biological psychology, the ideas of localisation and lateralisation can be illustrated, as can changes and differences in the brain and body relating to gender. If you draw yourself a diagram to illustrate a topic, always add detailed notes to explain it. Try redrawing the diagram from the notes alone. Alternatively, cover the annotations up (eg with Post-Its) and see if you can rewrite them accurately. However, be aware that just drawing a diagram in an exam is unlikely to earn you many if any marks, you need to be able to explain what it shows. Random Examiner 1. Download a random number generator (eg ‘undecided’)– or just get some dice. 2. Make two lists: i. one of topics you can be tested on AND ii. the other of possible question types you can be set. For example: a. i. research methods: eg lab experiment, field experiment, natural experiment, correlation, observation ii. describe, give strengths, give weaknesses b. i. study: decide which ones you need to know eg Peterson & Peterson, Murdock, Godden & Baddeley, Loftus & Palmer, Harlow, Stayton & Ainsworth Van Ijzendoorn & Kroonenberg, Hodges & Tizard, etc. ii. aim, method/procedure, findings, conclusion, give strengths, give weaknesses. c. i. theories: decide which ones you need to know eg Multi-store model, working memory model, Bowlby’s attachment theory ii. name topic, describe, give strengths, give weaknesses 3. a) Allocate a number (from 1 upwards) to each possible (sub)topic b) Allocate a number (from 1 upwards) to each possible question type. Note these two lists down. 4. Use your source of random numbers to generate number pairs. The first number determines to topic, the second what kind of question you have to answer. 5. Answer the question out load. If you are working in a pair, comment on the quality of the answer. If you are working alone, check your revision notes for any points that you are uncertain about. Test yourself To do this you can use your tables (cover up one row or column), labelled diagrams (cover up either the annotations or the diagram) etc. Alternatively, you could make yourself sets of cards with prompts or questions on. Practice with the ethics cards, then others of your own. You can also make them with questions on the front and answers on the back – practice with the Milgram cards. Practice questions Finally, it is critical that you practice answering questions. You should do both past paper questions and ones which have never come up before. Working with another students using past papers to guide you, try to make up your own questions covering a range of topics and question types. Downloads http://www.uniview.co.uk/doc/Self%20test%20cards.doc http://www.uniview.co.uk/doc/grid%20matching%20activity.doc http://www.uniview.co.uk/doc/random%20examiner%20activity.doc