Water and sanitation mapping - Overseas Development Institute

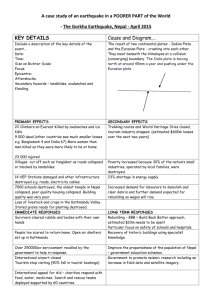

advertisement