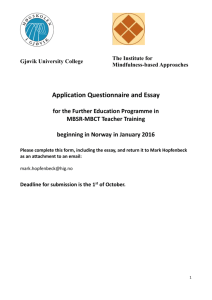

OPPGAVE PSYK 300

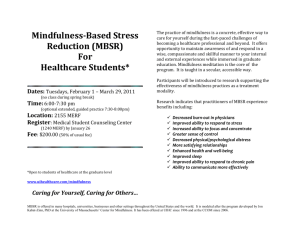

advertisement