RUPERTO K. KANGLEON 6th Secretary of National Defense May

advertisement

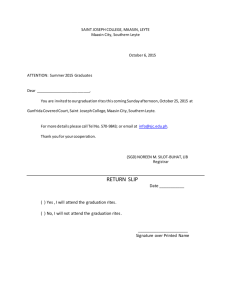

RUPERTO K. KANGLEON 6th Secretary of National Defense May 28, 1946 to August 31, 1950 A military strategist whose name is legendary in the pre-war Philippine Constabulary and during the guerilla campaigns against the Japanese occupation armies, Senator Ruperto K. Kangleon served his government and people since early youth. Kangleon was born in Macrohon, Leyte on March 27, 1890, as one of the six children – five sons and a daughter – of Braulio Kangleon and Flora Kadaba. He studied up to sixth grade in Leyte and had transfer and complete his elementary education in Surigao, because he refused to submit to what he considered was the over-bearing and oppressive conduct of some school authorities. Having graduated from the elementary grades, he went to Cebu, where he completed his high school course. Here he distinguished himself as all around star athlete, which won for him a berth in the First Philippines Olympic Team sent abroad in 1912-1913. After graduation from the Cebu High School, he went to Manila and enrolled in the College of Liberal Arts, University of the Philippines. But the military profession attracted him so he went to the Philippine Constabulary Academy in Baguio where he graduated in 1916. His first assignment after securing his commission as a young lieutenant fresh from military school was to fight “Oto”, the notorious Panay bandit whom he subdued in no time. This and other campaigns in the Visayas (Panay) and Mindanao Islands won him military citations and renown. He served with the Philippine Constabulary up to 1936 and later transferred to the Philippine Army. He was inducted into the United States Armed Forces in the Far East on September 1941. It was once told that Gen. Douglas MacArthur planned to land somewhere in Luzon, not in Leyte. Perhaps, MacArthur thought it would be a better strategy to recapture Bataan and Corregidor, the object of his vaunted promise: “I shall return.” But there was one man who opposed this move. He was Gen. Ruperto K. Kangleon, the leader of the guerrilla forces in Leyte. His indignation would forever be seen as a turning point in Philippine history. A MILITARY LIFE Kangleon was born on March 27,1890, in barrio San Roque, Macrohon in Southern Leyte, a 45-minute pumpboat ride to Limasawa Island. He was the second in Braulio Kangleon and Flora Kadava’s brood of six. Kangleon started his elementary education in his hometown and continued it in the neighboring town of Maasin, now a city and the provincial capital of Southern Leyte. He attended high school in Cebu City where he excelled in athletics and became a member of the Philippine Olympic Team. As a young man, Kangleon was admitted to the Philippine Constabulary School, the precursor of the Philippine Military Academy in Baguio City. Among his contemporaries were Ramon D. Gaviola Jr., former presiding justice of the Court of Appeals, and the late Rev. Mario G. Gaviola, former archbishop of Lipa City. Soon after finishing his degree in the military academy, Kangleon launched his military career, a much-coveted, luxurious and highly respectable line of work in those days. As a new officer-graduate, Kangleon’s baptism of fire involved combating outlaws and bandits in the provinces. Clad in shiny leather boots, wide-side khaki breeches, and a khaki shirt/coat — the prescribed military uniform of commissioned officers then — Kangleon led constabulary units in successful pacification campaigns against lawless elements. As a young lieutenant, he was also assigned to Imus, Cavite, a town noted for beautiful women. There he met Valentina Tagle, married her and together raised 10 children, the inspirations of his military career. WORLD WAR II After becoming provincial commander of Bohol and Cebu, World War II found Kangleon as the commanding officer of the 81st Infantry Division in Samar. As a Lieutenant Colonel then, Kangleon was ordered to proceed to Davao where he and his men valiantly fought the Japanese Imperial army. By virtue of his rank in the guerrilla movement, Kangleon was tasked to make advisories to Allied troops of the goings on in the province. And no less than General MacArthur trusted his opinion. That was why, when Kangleon suggested that the General land in Leyte instead of another place in the country, MacArthur listened. Kangleon gave him his guarantee that the united and well-organized guerrilla force in the province would be competent enough to secure the arrival of the American forces. Convinced, Gen. MacArthur landed in Leyte on Oct. 20, 1944, just like he promised several years before. From then on, Leyteños believed that Philippine liberation from Japanese domination would not have been complete without Gen. Kangleon. Kangleon’s image was, however, smeared when he surrendered to the Japanese. He was following the orders of his American superior, a certain Colonel Christaine. This made the once united Leyte guerrilla forces to become ragtag and disgruntled units that constantly and violently fought against each other for supremacy. Nevertheless, some people still kept their belief in Kangleon. Amid the anarchy, one man stood to protect Kangleon and said that he was the rallying figure that can unite the various guerrilla units because Kangleon was the highest-ranking military officer in Leyte. That man of faith was Graciano Kapili. Kapili, or Grasing to those close to him, was from Himatagon (now the town of St. Bernard). He took it upon himself to undergo the dangerous task of rescuing Kangleon who was then locked up in a Japanese military prison in Butuan. Filled with this dream of a united guerrilla movement, Grasing boarded a sailboat (kaba-kaba) and plowed to Butuan. Armed only with his antics, Grasing caught the amusement of the Japanese prison guards and was able to talk to Kangleon. Grasing convinced Kangleon that escape was the only way out of the Japanese-guarded prison. Kangleon and Grasing, therefore, made their dash to freedom and boarded the kabakaba and sailed to freedom without detection by the Japanese. They sailed to Leyte and arrived safely at barrio San Roque, Macrohon, the hometown of Gen. Kangleon, on Dec. 26, 1942. ON THE ROAD TO FREEDOM Adopting Tigulang (Visayan for old man) as his nom de guerre, Kangleon proceeded to re-unite the guerrilla forces in Leyte. Guerrilla leaders, including Captains Atilano Cinco (who later became Congressman) and Alejandro Balderan in the waray-waray areas, and even Americans — Capt. Gordon Lang who was a US Navy officer and Orville Babcock, former Leyte Division superintendent of schools — submitted themselves to his leadership. But one leader didn’t. Lt. Blas Miranda, a mere second lieutenant of the Philippine Constabulary (PC) before World War II that dubiously carried the rank of Brigadier General in a certain Camp Heaven in the mountains near Ormoc City, refused to recognize Kangleon’s leadership. Miranda took Kangleon’s surrender to the Japanese as an issue. The antagonism between Kangleon and Miranda reached a bloody climax when they met in armed combat in Baybay, Leyte. None of the two strong-willed guerrillas died, however. But later on, Miranda vanished for good after he narrowly escaped an unexpected Japanese raid on his camp. His men, leaderless, later found their way to the Kangleon camp. Since then, the guerrillas of the whole province of Leyte were united behind Kangleon. His hold and control over the Leyte guerrillas became easier because everybody knew Kangleon had the recognition and support of Gen. MacArthur. It was said that MacArthur had been in touch with Kangleon since January 1943 while MacArthur was still in his headquarters in Australia. In effect, MacArthur designated Kangleon as the military and civil governor of Free Leyte. From his headquarters in Australia, MacArthur gave instructions to Kangleon on the conduct of his military operations against the enemy and relations with the civilians. One such instruction was to avoid open armed engagements with the enemy to prevent Japanese reinforcements from going to Leyte and bloody confrontation that could harm civilians. Meanwhile, Gen. Kangleon maintained military liaison with Col. Wendel Fertig, the American guerrilla leader of Mindanao. Both guerrilla leaders were Gen. MacArthur’s contact persons in the Philippines. Fretig’s platoon of American guerrilla men bristling with their garand rifles, carbines and tommy guns from Australia, landed in Leyte. Wearing varied costumes from dark short pants to the traditional khaki uniforms, they marched in snappy military formation heading to the guerrilla headquarters situated in the central elementary school buildings in Bato, Leyte, to confer or exchange notes with their local comrades in arms, on the enemy movement in the area. Knowing that Allied forces neared Philippine shores, Japanese forces came and placed garrisons in every town of southwestern Leyte. The Japanese staged military forays that brought them to the mountains to flush out any armed resistance from the guerrillas. They even hunted down Gen. Kangleon, but to no avail since the civilians refused to cooperate. A FATHER'S SACRIFICE Provoked by the Japanese offensive, Kangleon and his men engaged in a hit-and-run attack against the Japanese in February 1944. The Japanese, in turn, launched search-anddestroy operations against Kangleon in the mountains. Failing to capture the man himself, the Japanese went after Kangleon’s four children and brought them to the mountains of Southern Leyte. They were held hostage there, in order to force the surrender of their father on the threat that they would be killed if Kangleon would not capitulate. Gen. Kangleon was locked in the horns of a painful dilemma: to surrender or not, knowing that his children’s lives were at stake. However, after some serious soul-searching, he decided not to surrender and offered his children as a sacrifice on the altar of his country’s cause, despite the pain in his heart. For his noble feat of patriotism, the late first bishop of Maasin, Most Rev. Vicente T. Ataviado, compared Kangleon to the Spanish General Moscardo whose soldier-son was captured by the enemy during the Spanish Civil War. Given the same choice, General Moscardo opted to sacrifice his son rather than surrender. While in captivity, Kangleon’s children kept praying the rosary. Their prayers were answered, since a Japanese officer named Captain Itzumi, befriended them and shared his Buddhist beads with them. The beads were given as a gift from Itzumi’s stepmother for his safety. He became their guardian angel and made their ordeal bearable. Meanwhile, Kangleon continued his service to the country despite the danger that has befallen his own flesh and blood. In the hope of instilling some inspiration and hope in the hearts of his men, and probably his own, he composed a song in Cebuano titled “Bantay Boluntaryo” (Watch Out, Volunteer Guards), setting it to the music of an old Philippine martial tune. Shortly before the Allied liberation forces landed in Leyte on Oct. 20,1944, the Japanese pulled out their garrisons. As one faintly recalled, the Japanese left Macrohon in July 1944, less than a year from their arrival in Nov. 1943. It was, however, speculated that the Japanese were merely regrouping with other Japanese forces in preparation for the expected American invasion. Meanwhile, in recognition of his spectacular achievements in the guerrilla movement, Kangleon was promoted to full colonel by Gen. MacArthur on Oct. 1,1944. True to his promise, MacArthur, accompanied by the Allied liberation forces, landed in Leyte on Oct. 20,1944. Beginning the long road to the liberation of the Philippines, MacArthur’s forces rescued Gen. Kangleon’s children in Tacloban City. Three days following the Allied landing, on Oct. 23,1944, Kangleon was appointed military governor of Leyte. Gen. MacArthur personally pinned on Kangleon the Distinguished Service Cross of the United States of America, a decoration awarded for extraordinary heroism in combat witnessed by Philippine Commonwealth president Sergio Osmeña as well as commanders of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, and even US Armed Forces at the Leyte provincial capitol building. IN POLITICS Kangleon became Leyte’s civil governor upon the re-establishment of the Philippine Commonwealth under President Osmeña. On May 28,1946, he was appointed Secretary of National Defense by Pres. Manuel Roxas, the first of the Commonwealth and the Republic of the Philippines, in the same way that Kangleon was the Defense Secretary during the closing American colonial rule in our country and held the position upon the declaration of independence on July 4,1946. But due to policy differences with the next president, Pres. Elpidio Quirino on the leadership of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, Kangleon resigned as Defense Secretary on Aug. 31, 1950. Kangleon was trying to ask President Quirino to remove the generals whom he considered deadwood to which the President disagreed. Kangleon’s resignation from the Cabinet paved the way for his entry into the political arena, an all too familiar field for his siblings. His brother, Ciriaco, was an Assemblyman (diputado) in the old Philippine Assembly, while the other brother, Tereso, was mayor of Macrohon, his native town. Kangleon ran for Senate even without the endorsement of the incumbent President Quirino. He became senator and was appointed chairman of the Senate Committee on Veterans and Military Pensions and vice chairman of the Committee on National Defense and Security. He championed the cause of the Filipino veterans by filing bills and resolutions for their welfare and advancement. However, even before he could finish his six-year term in the Senate, Sen. Kangleon succumbed to myocardial infraction on Feb. 27,1958, exactly a month away from his 68th birthday. The Filipino nation led by Pres. Carlos P. Garcia mourned his untimely death. THE NUMBER ONE LEYTEÑO At Kangleon’s funeral, former senator Lorenzo Sumulong extolled Kangleon’s virtues of patriotism and honesty. He described Kangleon as a “tried and tested patriot who braved a thousand deaths in the defense of his country” and a man of “honesty who was always beyond suspicion.” The solon also recalled that as over-all guerrilla chief of Leyte, Kangleon was authorized by Gen. MacArthur to issue war notes for the total amount of P2 million, a fortune during that time. If Gen. Kangleon had no moral qualms, he could have made it appear that the whole amount was spent and lined his pockets with wads of money, which he never did. Soon after the landing of the American liberation forces, Kangleon submitted an accounting showing that only one-fourth of the authorized P2 million was spent. In another instance, Kangleon returned an unexpected intelligence fund in the sum of P49,350 to the United States government with a corresponding receipt issued by the US Armed Forces, Pacific on June 26,1945. For his highly meritorious and distinguished services in the military, Sen. Kangleon was awarded 17 medals and campaign ribbons. Topping them was the Distinguished Services Cross of the United States of America, the one pinned on him by Gen. MacArthur. In memory of Southern Leyte’s outstanding son, a life-sized statue of Kangleon now stands on the campus of Saint Joseph College in Maasin City. Paradoxically, it took a nonLeyteño by birth, in the person of the late bishop Ataviado, to place in concrete the honor and recognition due the number one Leyteño. On the 50th anniversary celebration of the Leyte landing by the Allied liberation forces at Palo Leyte on Oct. 20, 1994, Gen. Kangleon was posthumously promoted to brigadier general after half a century and 36 years after his death. Probably, in deference to his wish which he must have expressed during his lifetime, Gen. Kangleon’s remains were transferred to his place of birth on Feb. 27,1994 from the Manila South Cemetery where he was buried with fitting honors on March 4,1958. In a world that is presently wanting for heroes, stories such as these are rare. But simply remembering or leafing through the pages of our past — such as the memories and legacies left behind by heroes and noble men such as the number one Leyteño, General Kangleon — is enough for us to have hope even in the darkest of times.