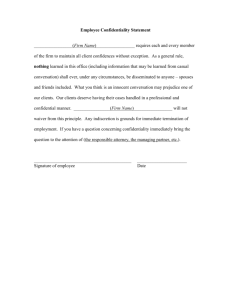

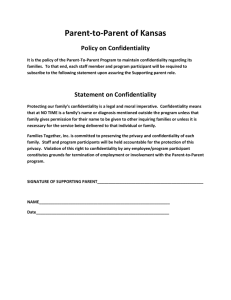

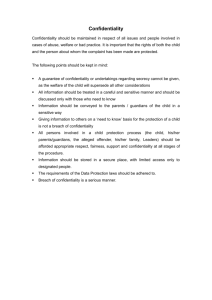

Module 7 The Ethics of Confidentiality and Privacy

advertisement