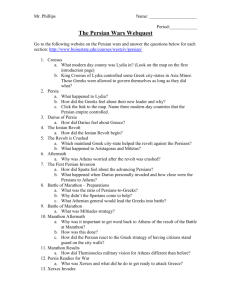

The Persian Wars

advertisement

The Persian Wars Greece fought for its very existence twice in the fifth century B.C. The Persian Empire greatest of all the mid­east empires, sent a large seaborne expedition against Athens in 490 B.C. Defeated by the Athenian army at Marathon, the Persian King of Kings, Xerxes, determined to punish the Athenians, overawe the rest of Greece, and go on to incorporate all of Europe into his empire: We will create a Persia that borders on the very sky of god. For the sun will not look down on any country that borders on ours; instead, I will, with your help, pass through all of Europe and make its lands one land. They will tell me this is the way things are: there won’t be a human city or nation of mankind left that will be able to oppose us once we have disposed of the people I’ve mentioned. Thus both the guiltless and the guilty will wear our yoke of slavery. (Herodotus, BK 7, Chap. 8 p. 158) Of course these words are put into the mouth of Xerxes by a Greek and an Athenian at that, the historian Herodotus. But the Greeks certainly believed them to be true. The Persian monarch was ruler by divine right, anyone summoned into his presence was required to prostrate himself and make obeisance—the Greeks saw such ritual as undignified and unfit for civilized people. The Persians represented a tyranny and barbarism to the Greeks and their undoubted wealth and power made them even more frightening. The defense of Hellas against the barbarian was a holy cause—states and individuals forgot ancient enmities in the name of what Winston Churchill called a “higher order of hatred.” Greeks from 31 different states took the following oath before the battle of Plataea and kept it: “I shall fight to the death. I shall put freedom before life, I shall not desert my leaders alive or dead, I will obey my generals’ commands, I shall bury my comrades where they fall and leave none unburied.” The opening act in the struggle was a large scale revolt among the Greek cities of Ionia against their Persian overlords. The Ionians did not act out of any burning desire for freedom but rather as a result of the schemes and bungled plans of some aristocratic leaders, but they did appeal to the mainland Greeks for assistance. The Spartans warned the Persians not to harm Greeks and the Athenians sent a few thousand soldiers to aid the 2 rebels—this small force burned a Persian provincial capital at Sardis and earned the wrath of tow succeeding Persian monarchs, Darius the great and his son Xerxes. Darius was so angry at the news of the burning of Sardis, he ordered a servant to stand behind him, “and repeat three times whenever serving dinner, ‘Master, remember the Athenians.’” It took a few years for the Persians to put down various revolts and prepare an expedition against Greece. Darius sent a sea­borne force against Athens in 490 B.C. The Persians attacked, destroyed and enslaved the small Polis of Eretria, making their intentions abundantly clear, and landed at Marathon because they were advised that the small plain there would be good ground for cavalry. The Athenians sent an army of about 10,000 hoplites to meet the Persians at the water’s edge. Miltiades, the Athenian commander consulted the organs of the sacrificial animals and with no further ado ordered a general attack: …the Athenians were unleashed, and they furiously charged the barbarians. There was a distance of no less than one mile between their spearpoints. When the Persians saw them advancing on the double,…they though the Athenians were rushing insanely to their utter destruction…But when the Athenians came to grips with the barbarians, what a fine account they gave of themselves! They were the first of all the Greeks…who used the tactic of charging the enemy line; they were also the first who could bear up under the sight of Persian uniforms and the men wearing them. Until that day, merely the word “Persian” was terrifying to the Greeks. (Herodotus (6.112) p. 153) The battle also demonstrated the tactical superiority of the heavily armored Greek hoplite over the Persian forces for the next century and a half. The small Athenian force revealed the weakness of the Persian Empire—its military forces were huge and numerous, but the heart was the Persian cavalry. All of the massive detachments of infantry were poorly trained and poorly motivated. Within Greece itself, Marathon was a shock. It marked the arrival of Athens as a political and military power of the first magnitude. The Spartans, traditionally the leading land­power within Greece, took no part in the battle because they were observing a religious festival. Marathon gave the Greeks, esp. the Athenians a breathing space and they made good use of it. The Athenians elected a statesman named Themistocles to a succession of offices he proved worthy of the situation. His first contribution was to convince his city that Marathon was not the end of the war but merely the first skirmish in a long struggle. 3 His second and greatest contribution was to create a viable strategy for the defense of his city and all of Greece. He went before the Athenians assembly and gave a great speech that convinced the citizens to commit the funds coming in from the state owned silver mines at Mount Laurion to build warships, instead of using the money for a tax rebate. In short, Themistocles, committed Athens to a naval strategy. Within 10 years, the Athenians turned themselves into a great naval power. Their fleet consisted of 200 triremes—a huge force that numbered, counting rowers, sailors and marines at least 35,000 men. In Plato’s disapproving words, Themistocles, “…turned the Athenians from steadfast soldiers into sea­tossed mariners… he deprived them spear and shield and degraded them to the rowing bench and oar,” (Plutarch, p. 81). Meanwhile the Persians acquired a new King, Xerxes and prepared in earnest for a showdown with the Greeks. The Persians determined that their best hope for victory lay in an overland march to Europe across the Hellespont and down through Thrace. The army would be supported by a fleet drawn from the subject peoples of the empire, the Phoenicians, Egyptians and Asiatic Greeks. The story of the Persian preparations is the subject of a lot of exaggeration by Herodotus. According to him, Xerxes amassed an army and a fleet that numbered over 5,000,000 men. As this great force marched towards Greece, they moved through districts like a horde of locusts devouring all the food and drinking the rivers dry. Of course, these numbers are absurdly large—perhaps the Soviet Union or the United States mobilized such figures for the Second World War, but no army even approaching that number was possible before the age of railroads and mass transport. Herodotus is simply making the point that the Greeks were greatly outnumbered. The size of Xerxes’ army? Your guess is as good as mine. Perhaps 500,000 would be conceivable. At any rate the Greeks reacted with a mixture of terror and anger to the news of the coming invasion. Xerxes sent ambassadors to all the Greek cities demanding gifts of water and earth, the traditional Persian symbols of surrender. The Spartans threw the Persians heralds down a well. In Athens, Themistocles persuaded to the assembly to order the execution of the heralds on the grounds that they had defiled the Greek language by using it to deliver the demands of a barbarian. Such acts of defiance must have felt good, but many Greek states saw little hope for survival. Only a handful of 4 Athenian statesmen and soldiers kept their nerve and persuaded their allies to remain firm—here once again, the skills and persuasiveness of Themistocles proved vital. Themistocles calculated that only a combination of Athenian naval power and Spartan land power could defeat the Persian threat. It would be very difficult to convince the Spartans to march in northern Greece to protect Athenian interests. Themistocles negotiations with the Spartans were long and difficult but a grudging co­operation was finally achieved. Throughout the entire Persian invasion Athens and Sparta were reluctant allies because their vital interests were at odds. Only the undeniable need of the Athenian fleet made the Spartan at all willing to assist Athens. The Greeks decided then reluctantly to meet the Persian onslaught in Northern Greece. When the Persians reach the Hellespont, Xerxes ordered his engineers to build a bridge of boats from Asia into Europe. This bridge, no sooner built, was destroyed by a sudden, violent storm: When Xerxes heard this, he became furious and ordered that three hundred lashes be laid on the Hellespont with a whip and that a pair of fetters be thrown into the water. I have even heard that he sent along men with branding irons to brand the Hellespont! He ordered the men to say these atrocious, barbarous words while flogging the stram: ‘Your master imposes this punishment on you O bitter water, because you did him wrong…King Xerxes will cross over you whether you like it or not.’…as to the men in charge of bridging the Hellespont, he ordered that their heads be chopped off. (Herodotus (7, 36) p. 167) Xerxes now moved down into Greece from the north, Herodotus comments that the Greeks guarded the south, “and the continent of Europe.” When the Persians eventually captured Delphi, a great war bellow was heard coming out of the temple of Athena—as the Persians ran away in terror, two huge spectral warriors were seen pursuing them—“or so I was told” wrote the ever, careful and skeptical Herodotus. The first great clash came at Thermopylae, the warm gates, a narrow pass close by the straits of Artemesium. The Greek fleet fought a two day battle here and inflicted heavy casualties on the Persians but the really memorable battle took place on land between a small force of Greeks under Spartan leadership and the whole vast Persian army. The core of the Greek force was King Leonidas of Sparta and a group of 300 bodyguards, Spartan citizens all. For several days that small force held off the Persians. Eventually local Greeks showed Xerxes a 5 path around the Greek defenses and the Spartans found themselves surrounded. Leonidas decided to fight to the death. The monument erected reads: Stranger, go tell the Spartans, Here we lie, obedient to their laws. However heroic was the Spartan defense of the pass, the battle put enormous pressure of Greek unity. The Spartans were on the verge of leaving the Athenians to their own devices and simply fortifying the isthmus of Corinth. It was here that Athenian leadership played its decisive role. As Herodotus put it: If someone were to say that the Athenians were the saviors of Greece, he would not fall short of the truth, because Athenians would have tipped the scales toward whatever side they inclined to. They chose that all Greece should live free, though… Sparta’s allies would have betrayed her, not because they wanted to, but because they would have been conquered one by one, by the barbarian armada. Then the Spartans would have been isolated, and even if they had performed great acts of heroism, they would have perished nobly and alone… Greece would have fallen to Persia. (Herodotus (7, 139) pp. 177­78) Themistocles had to balance the interest of his city with the defense of all Greece while dealing with a suspicious and reluctant group of allies. It was quite a performance. First, he had to convince the assembly to rely on the even if that meant deserting their homes and leaving the city of Athens to the Persians. He invoked the words of the oracle of Delphi: Then wide­viewing Zeus will grant Athena A wall of wood to be alone uncaptured, a boon to you Await not the coming of horses, the marching feet, the Armed host upon the land. Slip away, Turn your back, you will meet in battle anyway. O holy Salamis, you will be the death of a woman’s son Between the seedtime and the harvest of the grain. 6 The Athenians decided to stake everything on a sea battle in the narrow straits of Salamis. While Themistocles bribed and cajoled the rest of the Greeks to stay and fight at Salamis, the whole population of Athens left their homes and took boats to sail to the island. Themistocles convinced the Spartans to fight by combination of entreaty and threat: If you stay here, and having stayed act like a brave man—it will be the will of the gods; if not, you will be the downfall of Greece. The whole war depends on our ships. Do as I advise, then, because if you do not, we will put our families aboard our ships and go, just as we are to Italy… Then, when you have been forsaken by allies like us, you will, all of you, remember my words. (Herodotus, 8, 61) p. 216) Themistocles convinced the allies to fight at Salamis, but to make matters even more secure, he sent his slave to Xerxes with a message that the Greeks might try to escape and that the Persians ought to blockade the passage. On the morning of September 23, 480 B.C. Xerxes, “King of Kings,” walked up a hill just west of Athens and sat down on golden throne set there by his servants. Behind him, smoke rose from the burning buildings and temples of Athens. At his fleet lay the waters of narrow sound, a mile wide and three miles long which separated the island of Salamis, with all the women and children of Athens, from the coastline of Attica. Against the far shore lay the Greek fleet, about one half of it Athenian warships—it was tightly corked up by Persian naval forces at each entrance. The king gave the order to the Persian fleet to advance and then relaxed to watch the destruction. The fleets were large—390 Greek warships faced about 1200 Persians. The battle was a melee, fought at close range, in confined waters. Ships rammed, collided and soon the waters were full of disabled and burning hulks. Themistocles knew his home waters well however and he knew that a South wind would rise about mid­ morning and turn the waters of the sound very rough and choppy. The wind did not affect the low­lying sleek, Greek warships but the large Persian ships wallowed and pitched badly, exposing the lower hulls to the bronze rams of the Greek triremes. The Athenians led the attack—ramming enemy vessels or simply passing close by and splintering the oars and thus disabling the vessels and injuring the rowers. The Greeks then disengaged and moved on to the next target, the Persians tried to grapple and fight it out on the decks with spear and sword. By mid­day, hundreds of Persian ships, disabled 7 and sinking, clogged up the channel. Thousands of barbarians were swimming or sinking below the waves. The Greeks took no prisoners and speared swimmers like fish in a barrel. It was a Persian disaster: . . .most of the Persian ships were demolished at Salamis. Some were wrecked by the Athenians, others by the other Greeks. It was bound to turn out for the barbarians as it did because the Greeks went to battle in orderly formations while the barbarians fought out of formation and had no idea what they were doing. The next day the Greeks prepared for battle – they were still outnumbered but the Persian fleet had had enough. The faith of Athens in the Wooden Walls had been justified and the reluctant trust which the rest of the Greeks had place in Themistocles’ naval strategy was rewarded with victory. The loss of his fleet unhinged the whole Persian plan. Without a navy, Xerxes could not hope to force the Isthmus defenses and subdue the Spartans. Salamis saved Sparta as well as Athens. The Persians found themselves alone with a huge, hungry in a poor land. Xerxes chose to cut his losses and return to Asia. The Persians left behind a sizable force in northern Greece – the next year a smaller, but still serious Persian invasion of Attica took place. But this time the Spartans finally got on board. When they took the field in earnest they fielded an army of 80,000 men counting allies, Helots and light troops. Despite a serious weakness in cavalry, the Greeks, under the command of the Spartan regent Pausanias managed to rout the Persian army at Platawa killing all but 3,000 of the enemy according to Herodotus’ account. By all accounts, the main credit for this victory belongs to the grim, armored Spartan hoplites. The alliance of the 31 Greek states under the leadership of Athens and Sparta was a major achievement in the political history of a people so divided and quarrelsome as the Greeks. It should be remembered that many Greeks threw in with the Persians out of fear or conviction – oligarchical factions in Thebes and Argos refused to fight the Persians. The Spartans ultimately redeemed their reputation as the finest soldiers in Greece once they finally committed themselves to action. Nevertheless their narrow Peloponesian viewpoint was a major obstacle to any united Greek response to the invasion of Xeres. It 8 must be said however that no successful Greek coalition would have been possible without Spartan participation – so prestigious was the Spartan reputation for warlike skill that the rest of the Greeks would never have fought without Spartan leadership. But it was Athens who clearly produced the leading figure of the war in Themistocles. His decision to commit Athens to a naval strategy and his skill in carrying out that strategy in the face of reservations from his most powerful ally probably saved Greece. He received the gratitude of Greece: After this the Spartans brought him down to their country with them. They gave him a crown for wisdom. . .and they also presented him the finest chariot in the city and sent a guard of 300 picked young men to escort him to the frontier. It is related too, how at the next Olympic games, when Themistocles entered the stadium, the audience took no further interest in the athletes, but spent the whole day gazing at him, pointing him out strangers, and admiring and applauding him as they did so. Themistocles was delighted at this and admitted to his friends that he was now reaping the fruit of all his labors for Greece. (Phutarch) In the words of Thucydides, “. . .through force of genius and by rapidity of action, he was supreme at doing precisely the right thing as the right time.”