MODES OF LINGUISTIC COMMUNICATION

advertisement

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

UNIT III

Morphology

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

MORPHOLOGY

Morphology is the branch of Linguistics that studies morphemes, their different forms, the

internal structure of words, and the rules by which words are formed.

The word morphology consists of two morphemes, morph + ology. The suffix –ology means

‘science of’ or ‘branch of knowledge concerning’ and morph is derived from the Greek word

morphe meaning ‘form’. Thus, the meaning of morphology is ‘the science of word forms’.

Morphologists describe the constituent parts of words, what they mean, and how they may

(and may not) be combined in the world’s languages.

DERIVATIONAL and INFLECTIONAL MORPHOLOGY

The two major branches of Morphology are Derivational or Lexical morphology and

Inflectional Morphology.

Derivational or Lexical morphology studies the principles governing the construction of new

words, without reference to the specific grammatical role a word might play in a sentence. In the

formation of drinkable from drink, or disinfect from infect, for example, we see the formation of

different words, with their own grammatical properties.

Inflectional morphology studies the way in which words vary (or inflect) in order to express

grammatical contrasts in sentences, such as singular/plural or past/present tense. Boy and boys,

for example, are two forms of the “same” word; the choice between them, singular versus plural, is

a matter of grammar, and thus the business of inflectional morphology. Inflectional morphemes do

not change the grammatical category of a word. They show grammatical function.

Lexical morphology is concerned with the formation and structure of the lexical bases of

lexemes. It is complementary with inflectional morphology: it deals with those aspects of the

formation and structure of words that are NOT a matter of inflection.

Morphemes

A morpheme is the smallest unit of language that has a meaning or a grammatical function.

The morpheme cannot be broken up into smaller parts without seriously injuring or destroying its

meaning.

A morpheme may be represented by a single sound, such as the morpheme a- meaning

‘without’ as in amoral, or by a single syllable such as child and -ish in child + ish. A morpheme may

-1-

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

UNIT III

Morphology

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

also consist of more than one syllable: by two syllables as in lady; or by three syllables, as in

crocodile: or by four or more syllables, as in hallucinate.

In writing, individual morphemes are usually represented by their graphic form, or spelling;

e.g., -es, -er, un-, re-; or by their graphic form between braces, e.g., {-es}, {-er}, {un-}, {re-}.

Allomorphs

The variant forms of a morpheme are called its allomorphs. For example, the morpheme

used to express indefiniteness in English has two allomorphs: ‘a’ and ‘an’. They are in

complementary distribution:

‘an’ occurs before a word that begins with a vowel sound: an apple, an onion

‘a’ occurs before a word that begins with a consonant sound: a peach, a tomato

‘a’ and ‘an’ are therefore not two different morphemes, but two different variants of one and

the same morpheme.

Such variants are known as allomorphs. An alternative definition of morpheme, then, would

be a group of allomorphs that are semantically similar and in complementary distribution.

Another example of allomorphic variation is found in the pronunciation of the plural

morpheme –s in the following words:

cats /s/

dogs /z/

boxes /iz/

Simple and complex words

Words are made up of morphemes. Every word in every language is composed of one or

more morphemes.

Simple words consist of a single morpheme, e.g. friend. The word friend cannot be divided

into smaller parts (say, fr and iend or f and riend). It is a monomorphemic word.

Complex words consist of more than one morpheme, for example, the word friends

contains two morphemes –the noun friend plus a plural marker –s. Similarly, in the word unfriendly,

there are three morphemes: un-, friend, and –ly, each of which contributes some meaning to the

overall word.

-2-

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

UNIT III

Morphology

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

Table 1

Words consisting of one or more morphemes

One morpheme

boy, desire, hunt, magnet

Two morphemes

boys, desirable, hunter, magnetize

Three morphemes

boyishness, desirability, hunters, demagnetize

Four morphemes

gentlemanliness, undesirability, demagnetization

More than four morphemes

ungentlemanliness, antidisestablishmentarism

Roots and Affixes

Complex words typically consist of a root morpheme (or stem) and one or more affixes.

The root constitutes the core of the word and carries the major component of its meaning. The root

is a lexical morpheme that cannot be analyzed into smaller parts. A root may or may not stand

alone as a word (drink does; ceive doesn’t).

Unlike roots, affixes do not belong to a lexical category and are always bound morphemes.

For example, the affix –er is a bound morpheme that combines with a verb such as teach, giving a

noun teacher with the meaning ‘one who teaches’.

Bases

A base is the form to which an affix is added. In many cases, the base is also the root. In

books, for example, book is the root to which the affix –s is added. In other cases, however, the

base can be larger than the root, which is always just a single morpheme. This happens in words

such as blackened, in which the past tense affix –ed is added to the verbal base blacken – a unit

consisting of the root morpheme black and the suffix –en. In this case, black is not only the root for

the entire word but also the base for -en. The unit blacken is the base for -ed.

Types of Morphemes

Morphemes are grouped into two broad types: free morphemes and bound morphemes.

1.

Free (or independent) morphemes are those morphemes which can stand alone as words.

They have a meaning or fulfill a grammatical function; e.g., boy, eat, he, and.

2.

Bound (or dependent) morphemes are those morphemes which cannot normally stand

alone but which are typically attached to another form e.g., -er in worker, -er in taller, -s in

walks, -ed in passed, re- as in reappear, un- in unhappy, undo, -ness in readiness, -able in

-3-

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

UNIT III

Morphology

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

adjustable; etc. These morphemes are also called affixes. So, all affixes in English are bound

morphemes, i.e. they are never words by themselves but are always parts of words.

Free morphemes

There are two types of free morphemes:

a)

Lexical or content morphemes (also called lexemes) are free morphemes that have

semantic content (or meaning) and usually refer to a thing, quality, state or action. Nouns,

verbs, adjectives and adverbs are lexemes, e.g., cat, Daniel, book, happy, hungry, slowly, like,

read, live, dog. These morphemes are words which carry the ‘content’ of the messages we

convey.

Lexical morphemes belong to the ‘open’ class of words i.e., a class of words that can

increase because we can add new lexical morphemes to the language rather easily.

b)

Functional or grammatical morphemes are free morphemes which have little or no meaning

on their own, but which have a grammatical function. For example, the articles the and an

indicate whether a noun is definite or indefinite -the boy or a boy.

In a language, these morphemes are represented by pronouns, auxiliary verbs, prepositions,

conjunctions, articles, e.g., we, can, with, because, and, the, a. Because we almost never add

new functional morphemes to the language, they are described as ‘closed’ class of words.

A morpheme performing a particular grammatical function may be free in one language and

bound in another. For example, the English infinitive marker to (as in the verb phrase to work) is a

free morpheme. It can be separated from its verb by one or more intervening words, as in to

always pay attention in class. In Spanish, however, the verb trabajar consists of the root trabajand the infinitive morpheme –ar, which are tightly bound together in a single word and cannot be

split up.

Bound morphemes

There are two types of bound morphemes: affixes and bound roots.

a)

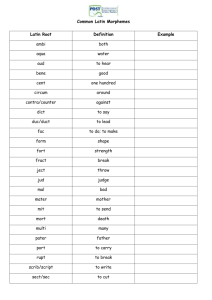

An affix is a bound morpheme which is attached to a word and which changes the meaning or

function of that word; e.g., -ment in development, en- in enlarge; ’s in John’s; -s in dogs, -ing in

studying, etc.

b)

A bound root is a root which cannot occur as a separate word apart from any other

morpheme, e.g. –ceive in receive, perceive, conceive and deceive; -tain in retain, contain;

-4-

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

UNIT III

Morphology

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

huckle- in huckeberry, cran- in cranberry; -mit in remit, permit, commit, submit, transmit and

admit.

Other common words with bound roots include un-kempt, un-gainly, in-ept, dis-cern, and nonplussed, to name but a few. These words consist of a prefix plus a root that cannot be used by

itself.

Bound roots are root morphemes that cannot be used as words and therefore do not belong to

a conventional lexical category such as noun or verb.

Types of Affixes

Affixes can be classified into two different ways: according to their position in the word and

according to their function in the language.

1)

According to their position in the word they are attached to, affixes are classified into prefixes,

infixes, suffixes and circumfixes.

A prefix is an affix that is attached to the front of its base, e.g. un- in unnoticed, a- in amoral,

sub- in subway, etc. Notice that prefixes are represented by the morphemes followed by a

hyphen (-).

A suffix is an affix that is attached to the end of its base; e.g., -able in noticeable, -less in

careless, -s in seeks, -en in shorten, etc. Notice that suffixes are represented by the

morphemes preceded by a hyphen.

An infix is a type of affix inserted within another morpheme. There are no infixes in the

English language, but the Philippine language Tagalog has infixing. For example the infix

-um-, which is inserted after the first consonant of the root to mark past tense.

Table 2

Some Tagalog infixes

Base

Infixed form

bili

‘buy’

b-um-ili‘

‘bought’

basa

‘read’

b-um-asa

‘read’ (past)

sulat

‘write’

s-um-ulat

‘wrote’

A circumfix is a discontinuous morpheme that surrounds a root. Many past participles in

German and Dutch are formed through circumfixing.

-5-

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

UNIT III

Morphology

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

Table 3

2)

Some German circumfixes

ge-kann-t

‘known’

ge-zeig-t

‘shown’

ge-läute-t

‘rung’

According to the function that affixes fulfill in the language, they are classified into

derivational morphemes (or derivations) and inflectional morphemes (or inflections).

Derivational morphemes are bound morphemes that produce new words from existing ones.

They are often used to make words of a different grammatical category. Thus, the addition of

the derivational morpheme –ful changes the noun doubt to the adjective doubtful. In English,

derivational morphemes can be either prefixes or suffixes.

Table 4

Some English prefixes and suffixes

Prefixes

Suffixes

dis-appear

happi-ly

re-write

friend-ship

il-logical

neighbour-hood

un-comfortable

art-ist

Inflectional morphemes are bound morphemes that indicate aspects of the grammatical

function of a word. They are not used to produce new words in the English language.

Inflectional morphemes change the form of a word but not its lexical category or its central

meaning. They create variant forms of a word to conform different roles in a sentence or in

discourse.

On nouns and pronouns, inflectional morphemes serve to mark semantic notions such as

number and grammatical categories such as gender or case. On verbs they can mark tense or

number, while on adjectives they indicate degree.

English has only eight inflectional morphemes.

-6-

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

UNIT III

Morphology

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

Table 5

English inflectional affixes

Nouns

Plural –s

the books

Possessive (genitive) –'s

my brother’s books

Verbs

3rd person singular present tense-s

He works hard.

Present participle -ing

He is working.

Past tense -ed

He worked.

Past participle-en / -ed

He has eaten / worked.

Adjectives

Comparative –er

the smaller one

Superlative -est

the smallest one

Inflection versus Derivation

We can use three criteria to distinguish between derivational and inflectional morphemes:

Category change. An inflectional morpheme never changes the grammatical category of a

word. For example, in the verb helped the past tense suffix –ed indicates that the action took

place in the past, but the word remains a verb and it continues to denote an action.

In contrast, derivational suffixes can change the category and/or the type of meaning of the

form to which they apply. The adjective sweet becomes the verb sweeten if we add the suffix

–en.

Order. Inflection takes place after derivation. Whenever there is a derivational suffix and an

inflectional suffix attached to the same word, they always appear in this order: the derivational

suffix is followed by the inflectional suffix. In the word farmers, first the derivational –er

attaches to farm, then the inflectional –s is added to produce the plural noun farmers.

Productivity, i.e. the relative freedom with which morphemes can combine with bases of the

appropriate category. Inflectional affixes typically have relatively few exceptions. The suffix –s,

for example, can combine with virtually any noun that allows plural form. In contrast,

derivational affixes characteristically apply to restricted classes of bases. Thus, -ize can

combine with only certain adjectives to form a verb.

modern-ize

*new-ize

final-ize

-7-

*permanent-ize

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

UNIT III

Morphology

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

INFLECTIONAL MORPHOLOGY

Virtually all languages have contrasts such as singular versus plural, and past versus

present. These contrasts are often marked with the help of inflection, the modification of a word’s

form to indicate grammatical information of various sorts –information about tense, aspect,

number, person, case, and so on.

Some languages have large inventories of inflectional morphemes. Finnish, Russian, and

German maintain elaborate inflectional systems. In the Romance languages (languages

descended from Latin), the verb has different inflectional endings depending on the subject of the

sentence. The verb is inflected to agree in person and umber with the subject, as illustrated by the

Spanish verb ‘hablar’ meaning ‘to speak’.

Table 6

Spanish verb inflections

Yo hablo

I speak

Nosotros hablamos

We speak

Tu hablas

You (singular) speak

Vosotros hablais

You (plural) speak

El / Ella habla

He / She speaks

Ellos / Ellas hablan

They speak

By contrast, English has a ‘poor’ or ‘weak’ inflectional system. This means that English has

relatively little inflectional morphology compared to languages that have morphologically ‘rich’

systems, systems that morphologically express grammatical relationships in productive ways.

English is no longer a highly inflected language. Today it has only eight bound inflectional

affixes, two on nouns, four on verbs, and two on adjectives, as shown in Table 5

HOW INFLECTION IS MARKED

The most common inflection involves affixation (suffixation in the case of English).

However, inflection can be marked in a variety of other ways as well, including by internal change,

by suppletion, by reduplication and by tone placement.

Internal Change

Internal change or ablaut signals a grammatical change by substituting one vowel for

another in a lexical root. In English, some irregular verbs form their past tense by changing the

vowel. Some irregular plurals also undergo vowel alternation. Table 7 contains examples of

internal change in English.

-8-

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

UNIT III

Morphology

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

Table 7

Internal change in English

sing (present)

sang (past)

sink (present)

sank (past)

drive (present)

drove (past)

feed (present)

fed (past)

hold (present)

held (past)

foot (singular)

feet (plural)

goose (singular)

geese (plural)

tooth (singular)

teeth (singular)

man (singular)

men (plural)

woman (singular)

women (plural)

Suppletion

Suppletion replaces a morpheme with an entirely different morpheme in order to indicate a

grammatical contrast. Examples of this phenomenon in English include the use of went as the past

tense form of the verb go, and was and were as the past tense forms of be. Two common

adjectives good and bad have suppletive comparative and superlative forms: better, best and

worse, worst respectively. In these cases of total suppletion, the suppletive forms share nothing

at all with the original root.

In English there are also some examples of partial suppletion, in which nearly the entire root

is replaced by a completely different form, leaving only the original root onsets, e.g. caught,

bought, thought, taught and sought, which are the past forms of the verbs catch, buy, think, teach

and seek.

Reduplication

Reduplication is the process by which a morpheme or part of a morpheme is repeated to

create a new word with a different meaning or different category. Partial reduplication repeats

only part of the morpheme, while full reduplication reduplicates the entire morpheme.

English makes no systematic use of reduplication to show grammatical contrasts, but this

process is common in other languages such as Turkish, Indonesian and Tagalog. Turkish uses

total reduplication to form the plural of nouns. Tagalog, on the other hand, uses partial

reduplication to indicate future tense in verbs.

-9-

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

UNIT III

Morphology

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

Table 8

Some examples of full reduplication

Base

Reduplicated form

Indonesian

rumah

‘house’

rumahrumah

‘houses’

ibu

‘mother’

ibuibu

‘mothers’

Table 9

Some examples of partial reduplication

Base

Reduplicated form

Tagalog

lakad

‘walk’

lalakad

‘will run’

kain

‘eat’

kakain

‘will eat’

Tone placement

Another morphological process often used to signal a contrast in grammatical meaning is

the use of tone. In Somali, one way in which some nouns can be pluralized is by shifting the high

tone on the penultimate syllable in the singular form onto the final syllable in the plural.

Table 10

Some examples of tone placement

Somali

Singular

Plural

árday

‘student’

ardáy

‘students’

díbi

‘bull’

dibí

‘bulls’

mádax

‘head’

madáx

‘heads’

- 10 -

Escuela Superior de Comercio Gral. José de San Martín

UNIT III

Morphology

Profesorado para Educación Secundaria en Inglés

Lingüística General

Profesora Norma Argota

Summary

The classification of morphemes may be represented diagrammatically as follows:

Figure 1

Classification of English morphemes

Content or lexical

words (Open class)

nouns, adjectives, lexical verbs, adverbs

Free

Functional or

grammatical words

(Closed class)

conjunctions, prepositions, articles,

pronouns, auxiliary verbs

Prefix un-, preMorphemes

Derivational

Affix

Suffix -ly, -tion

Inflectional

Bound

Suffix -ing, -s,

-ed, -en, -er, -est,

-s, -'s

Root

-ceive, -mit, -cran, tain

Bibliography

Denham, Kristin and Anne Lobeck. 2010. Linguistics for Everyone. Wadsworth. Cengage

Learning.

Fasold, Ralph W. and Jeffrey Connor–Linton (Eds). 2006. An Introduction to Language and

Linguistics. Cambridge University Press.

Finegan, Edward. 2004. Language: Its Structure and Use. 4th Edition. Thomson/Wadsworth.

O’ Grady William, Archibald J, M. Aronoff & J. Rees-Miller. 2005. Contemporary Linguistics.

An introduction. Fifth edition. Bedford / St. Martin’s.

Yule, George. 2006. The Study of Language. 3rd Edition. Cambridge University Press.

- 11 -