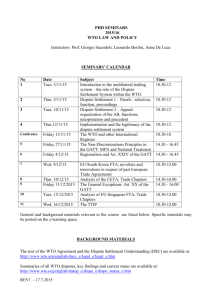

Broadening the Scope of Remedies in WTO Dispute Settlement

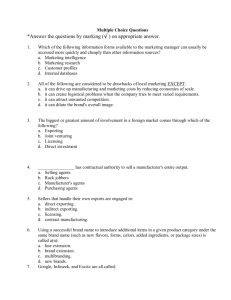

advertisement