Applying conflict sensitivity in emergency response

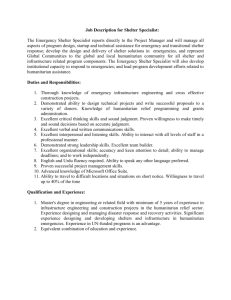

advertisement