The enigma of the female military-styled pop - Inter

‘Glamazons’ of Pop.

The enigma of the female military-styled pop star

– Kate Bush and Madonna

Michael A. Langkjær

Abstract

Female pop stars have assumed a military look to acquire a strong visual hook or „brand‟. By so doing, they transform themselves by taking on archetypically male qualities, while at the same time assuming these same qualities for reasons by turns ironical, aggressive and „caring‟. But if there is an essential difference between the military look of the female pop star and that of the male, what does it consist in? In a brief but comprehensive review of pop „glamazons‟, I shall deal mainly with Kate Bush and Madonna. Both pushed boundaries in mainstream popular music by their lyrics and imagery.

Art rock star Kate Bush has promoted „Wuthering Heights‟ as a chain-mailed sword-wielding knight (1978), performed as a gun-slinging space cowgirl on the „Tour of Life‟ (1979) and engaged in field combat in „Army Dreamers‟

(1980). Pop rock star Madonna has appeared smartly in military greatcoat with epaulettes and big, brassy buttons in „The Girlie Show‟ (1993), has had to pull her „American Life‟ anti-war fashion statement (2003) and returned to military style in „Express Yourself‟ on her „Re-Invention tour‟ (2004). In comparing Kate Bush and Madonna, I shall consider what their military look consisted in – including historical and mythological connotations, when and why a particular version of the look was worn, to whom and what it was directed and whether the object was aesthetic, political or commercial, as well as inquire into how it could relate to what is being expressed in the lyrics and its possible impact on current fashion. Was there a common denominator in Kate‟s and Madonna‟s military looks? If not, what were the main points of difference? What are the implications for fashion and gender studies?

Key Words: Fashion, politics, and ideology; style; fashion as performance, gender, sexuality, fashion icons, fashion and music, cultural studies.

*****

1. Introduction: Enigma variations

Female rock artists kitted out in military have run the gamut from wearers of fanciful faux (like ABBA ) or 60s-style regimental vintage (like

Suzanne Vega, Joan Baez, and Denmark‟s Linda Andrews), over embattled

2 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________ urban jungle survivors in empowering camouflage (like Lauryn Hill of The

Fugees , Deborah Anne Dyer of Skunk Anansie, and Beyoncé of Destiny‟s

Child ), through those whose militant radical chic is ideologically motivated

(like Inge Johansson of the Socialist Swedish group International Noise

Conspiracy ), to incidental users of part of some uniform in promotional news items and fashion reportage (like Annie Lennox as Greenpeace fundraiser in

Moscow posing in a Red Army fur cap, or Debbie Harry styled in a military jacket and fur neck wraparound to underscore her “trademark combination of softness and directness”).

1

A genuine warrior woman might occasionally appear in the shape of, for instance, Tori Amos and, as we shall see, Kate

Bush. For the sake of convenience I have restricted myself to the military styles of Kate Bush and Madonna.

The male pop star who adopts a military look need not be doing so to protest or to subvert. He may just be aiming at a strong, aesthetically heroic and erotic visual hook.

2

By their very intrusion into a traditionally masculine preserve, similarly clad female performers would more likely be doing it as a form of irony, as well as playing on the discomfiting notion of the human female as fighter. „Glamazons‟ are glamorous female pop stars who have incorporated, adapted and revitalized the warrior Amazon archetype in their performance representations of capable, strong-spirited women.

3

This does not, however, preclude their also appearing in male guises. It has been said that “when it comes to women in rock, confusion breeds confusion”

4

– a confusion all the more plain when dealing with female performers who are treating images and themes of war, warriors and deeds of arms. Bafflement is perhaps a better word. In protesting against war, Kate

Bush‟s „Army Dreamers‟ and Madonna‟s „American Life‟ are presumably expressing a female hardwired reflex to be nurturing and to preserve life rather than take it. But you also get macho power projections of the archetypal male attributes of warrior, uniformed soldier and gunfighter, complete with phallic swords and guns, such as in Kate‟s „James and the

Cold Gun‟ and Madonna‟s „Holiday‟. And what is one to make of Kate as

„Babooshka‟, reclaiming the prototypal female warrior of myth and history, or Madonna being dubbed a “20 th

Century Boadicea” and thus being likened to an ancient Briton warrior queen?

5

Or of the military references and accoutrements that figure in Kate‟s stage performance of „Oh England My

Lionheart‟ and Madonna‟s TV-spot „Rock the Vote‟?

Erotic, aggressive and violent imagery is a significant part of the military-styled performances of both women.

6

Their attraction to themes of violence and conflict raises questions of „Why?‟ and „For what purpose?‟

Remarks by Kate exemplify the motivating psychologies and aesthetics:

“What I find so interesting [is] the drive behind human beings and the way they get screwed up” and “Grotesque beauty attracts me. Negative images are often so interesting.” 7

Madonna says that “men have always been the

Michael A. Langkjær 3

______________________________________________________________ aggressors sexually...always been in control…sex is equated with power...and that‟s scary in a way...it‟s scary for women to have that power.” 8

That, along with Kate Bush‟s acknowledgement that “If you‟re female, then it‟s up to you to prove yourself,” 9

suggests that both women adopted the military look in a bid for empowerment.

10

Born in 1958, English Kate Bush and American Madonna are of the same age.

11

In 1978 Kate came out with the hit song „Wuthering Heights,‟ which reached number 1 on pop charts all over Europe, and by 1982 she had

12 become one of the most popular singers.

Madonna, hell-bent on making it, transcended her social class and cultural origins and lived out the American

Dream, becoming arguably “the most famous female in the world.” 13

International stardom began in 1984 with the song „Like a Virgin.‟ 14

Madonna‟s „camp-pop‟ aims at a wide, principally young female audience, while Kate‟s work is classified as alternative art-pop and prog-rock.

15

This may be doing an injustice to Madonna, whose music not only „matured‟ into rock, but addressed a public assumed to be aware of both personal and

16 political issues, conflating sexual and artistic with political freedom together with deliberate provocation and playful interrogation of American mentality.

17

2. Grounds for gendered ‘masculine’ performance

With its breathtaking vocal range, Kate‟s voice slides through a large number of vocal registers, producing an effect termed „sonic cross dressing‟, not unlike the vocal talent of those who performed Wagnerian roles as warrior-goddesses and huntresses.

18

This natural quality of voice has enabled Kate to move into a masculine space.

19

Madonna‟s singing voice is not particularly distinct from other female popular music voices, so that, along with some attempts to cross-gender her voice,

20

even to “a deep, wounded growl fired by brute desire…like it‟s coming from somewhere dark and menacing [so that] as far as you can tell it sounds like a man,” 21

she relies on strong visual signatures that play on androgyny. Madonna‟s trademark sonic vocoding is an artificial mating of male-based technology and female representation, an empowering passage into the male world of automatism, practically turning her into a male/female cyborg-like character.

22

Both women are self-managed control freaks already androgynous in taking on the role or persona of the producer.

23

Kate harks back to the romantic mythotype of the heroic genius, while Madonna is a latter-day

American CEO, calling the shots, and with, as she styles it: “a dick in her brain.” 24

Their master of persona-skipping was David Bowie, with his anno

1972-73 Ziggy Stardust doppelganger.

25

Like Bowie, Kate Bush and

Madonna are ever shape-shifters, female tricksters, recalling that the trickster-figure, an archetypal disruptor who “changes the rap to slip the trap” and snatches power, is ordinarily male.

26

Although never staged or videoed, a

4 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________ readily perceived example of Kate‟s artistic ability to transcend gender roles and play the soldier is „Pull out the Pin‟, where she takes on the persona of a

Viet Cong guerilla preparing to kill his American victim as he clutches his silver Buddha in his mouth.

27

At the 1991 Oscar Night, Madonna in a

Gentlemen Prefer Blonds and Diamonds Are a Girl‟s Best Friend send-up, shouted “Talk to me General Schwarzkopf, tell me all about it”, thereby situating herself “as [being] as important as the Gulf War, if not more, [and] at the very least...the equal of the political leaders of this world, and of great generals, [not] a bimbo.” 28

The press-impression of Kate Bush as an “impish hippy girl” and her refusal of the role of pop-lass had left her wishing for a more rocker, macho, ballsy character, “yearning for her own music to have a bit more bite and punch. More guts.” 29

It is a desire for male strength which she shares with Madonna, who, along with hard-boiled health, biceps and crotch-grabs, continuously uses the term „balls‟ to connote strength, power, and bravado.

30

Both women are embodying „new feminism‟, which has women as confident sexual agents with fluid identities.

31

3. 1 st

aspect of Kate Bush’s and Madonna’s gendered military style

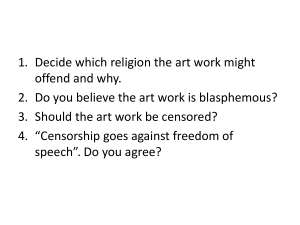

Lots of directed thought went into what Kate Bush and Madonna were doing. We mustn‟t assume that they did not understand much of their own discourse and were playing with references that they hadn‟t really grasped.

32

I have already hinted at the presence of a common element of irony. It seems somehow always present, in spite of the serious, even tragic dimension in their approach to the military theme. So, having dealt with the premises behind Kate‟s and Madonna‟s masculinization of their muses, let‟s examine some different aspects of their military-styled stage and video performances.

33

The first is the womanly and empathetic aspect of protest against war and loss, typified by Kate Bush‟s „Army Dreamers‟, and by Madonna‟s

„American Life‟.

34

According to Kate, “„Army Dreamers‟ is about a grieving mother who, through the death of her soldier son, questions her motherhood.” 35

Back in 1980 „Army Dreamers‟ took two differing shapes as a visual choreographic piece: that for the TV show „RockPop‟ in Germany, and that for the promotional video.

36

For Germany, Kate dressed as a haggard, barefooted cleaning-woman in an improvised costume comprising an old jumble-sale dress, a pair of pink rubber gloves and her mother‟s head scarf, kitchen apron and wooden broom.

37

The weary mother reflects on the death of her son, a soldier killed on duty. Kate cringes behind three soldiers, who, in British army camouflage, march, prowl and stand at attention. The song ends with the three soldiers cowering in a group, Kate spread-eagled protectively before them.

38

Michael A. Langkjær 5

______________________________________________________________

The promotional „Army Dreamers‟ video opens with a close-up of a mascara-rimmed eye blinking each time a rifle bolt clicks home.

39

The camera draws back to show Kate, the band and extras, dressed as soldiers, running through woods dodging pyrotechnics.

40

Kate‟s makeup marks her off as undoubtedly female. That and her voice serve to mark off the boundaries between her as narrator and performer, and the soldiers as supporting characters. Such a mismatch in costume and makeup tantalizes us: Is Kate personifying the mother, waking up from a dream illustrated in the action of the video? Or is she a cross-gendered representative of all of us as entranced army dreamers?

41

The Ulster conflict was in an urban setting and the setting of Kate‟s video is in a wood, which lends plausibility to her denial that

„Army Dreamers‟ had anything to do with the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

42

It is a critique of the military as a perverted dream machine.

What caused a ruckus at the April 2003 release of Madonna‟s

American Life album was her sleeve-image done in the likeness of Che

Guevara along with some exquisitely badly-timed scenes of war in the promo-video.

43

For the album sleeve, Madonna is pictured in a black beret mimicking Fidel Castro‟s personal photographer Korda‟s famous 1960

„ Guerrillero Heroico ‟ photo of Che in stark white/red/black, with what some saw as “two bleeding gashes on her eyebrow”, and others as “two red stripes

44 daubed like warrior paint on her face.” Madonna liked what Che represented and was feeling revolutionary, claiming she had recently “dreamt a Nazi party had seized control of America” and that she was a resistance fighter.

45

On the single sleeve, the paramilitary theme and the artistic composition invite comparison with the 1974 image of newspaper heiress turned urban guerrilla Patty Hearst looking “ferociously chic” in a

Symbionese Army publicity photo.

46

Madonna‟s style-metamorphosis was followed up in an 8-page portfolio for Q Magazine in May 2003 of a series of photos of her which Craig McDean had done already back in January 2003;

47 this work had a military theme, with Madonna posing in dark greens and anarchist blacks, combat boots, and holding guns. It has been remarked that these look like typical fashion shots without any hint of irony or distancing from the military theme; McDean had also done those for the album and the

CD booklet, where Madonna totes an Uzi submachine gun, her body in various martial-arts poses spelling out the letters of her name.

48

The video starts off with a fashion show with models decked out in military gear strutting down the catwalk accompanied by background images of warplanes in flight.

49

During the chorus, a peak-capped, uniformed

Madonna sings against a black screen as orange fireballs erupt over her shoulders. She is first seen with her distraught female army buddies in toilet cubicles, scoring the words „protect me‟ onto the partition with a combat knife. They kick their way into a sexy dance routine, with Madonna leading as an NCO. She and her four female comrades in military garb then drive a

6 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________

Mini Cooper through the wall and crash onto the catwalk, spraying a roofmounted water cannon at the paparazzi and crowd, juxtaposed with rapid edits of planes dropping bombs, and mushroom clouds alternating with a fuck-finger. A climax of graphic war images, badly maimed soldiers and blown off limbs ends with Madonna throwing a hand grenade which is caught by a President Bush look-alike, who transforms it into a lighter to light his cigar.

50

On April 1 st

, one day after it was first shown on a few music channels, Madonna chose to pull the video.

51

It was the first time she had ever shown reluctance to offend, which some saw as a copping out, others as just another carefully orchestrated publicity stunt.

52

But no artist wanted to be the next Dixie Chicks, who, on top of Chick Nathalie Maines‟ statement that she was “ashamed President Bush is from Texas,” experienced falling album sales and having their music yanked out of radio playlists.

53

Madonna had originally wanted the video to convey strong anti-war, anti-materialism and

54 anti-fashion industry statements.

Instead, an edited version much weaker than the original was released; it only contains the footage of the peak-capped

Madonna singing in front of 165 alternating flags of the world.

55

The surreally mascara-and-lipstick-made-up and combat-attired

Kate of the 1980 „Army Dreamers‟ video was exotic; Madonna as a field uniformed NCO in the „American Life‟ video anno 2003 is not; a fact as likely as not owing something to the cinematic fiction of Private Vasquez in

Aliens anno 1986 and Demi Moore in G.I. Jane anno 1997, as well as to women having served on the frontlines in the Gulf and Iraq.

56

Both videos had fast-paced images of the stars acting out the part of soldiers in combat.

But while the vague and arty Kate had met with critical approval by showing herself capable of writing songs with „issue status‟, without being labelled a

„cause lyricist‟, the notoriously unsubtle Madonna had had to reassure folks in the States that “I feel lucky to be an American”, and nonetheless ended up deciding to pull her video.

4. 2 nd

aspect

The second aspect is that of new-feminism empowerment being expressed through macho imagery and phallicism, typified by Kate Bush‟s

„James and the Cold Gun‟ and „Babooshka‟, and by Madonna‟s „Holiday‟.

57

„James and the Cold Gun‟, a rock number, tells the story of James, a cowboy outlaw who is running away from humanity.

58

In her 1979 „Tour of Life‟ stage performance of the song, Kate was in a black, figure-hugging fringed cowboy suit with gold trim and elbow-length gold-coloured gloves packing a six-shooter in a low-slung holster that, with an Emperor Ming-styled gold collar, gave her the look of “a futuristic space cowgirl.” 59

Towards the end of the song, Kate toted a shotgun with which she gunned down several cast members and the audience.

60

Kate explained: “My imagination runs like a

Michael A. Langkjær 7

______________________________________________________________ non-stop B-movie with me as the star...It gives me excitement, a savour of heroism…I really like guns. Not what they do, but detach them from their purpose and they‟re...fantastic, beautiful...I‟ve never actually shot anyone, but in a song I can do it, and in some ways it‟s much more exciting, more symbolic.” 61

This recurring gun-fascination is but another aspect of Kate‟s

„male‟ identity: stills from „James and the Cold Gun‟ show her firing from the crotch.

62

„Babooshka‟ tells the story of a woman disguising herself as an alluring stranger, trying to gain the attention of her husband.

63

In the 1980

„Babooshka‟-video, Kate shifts between a veiled lady dressed all in black and mourning her waning relationship, and a voraciously sexual, sword-wielding and phallic woman. The latter is adorned in what has been described as “an outfit that Warrior Princess Xena would envy – a tight-fitting chainmail bra, green bikini bottom, gold straps that wrap around the top of her thighs.” 64

Kate‟s body looks muscular and powerful, expressing high eroticism as she waves her phallic blade.

65

The usage of swords by women can be understood as a form of phallic empowerment, putting them on a man‟s level.

66

In Madonna‟s 1993 „Girlie Show‟, with costumes for the tour designed by Italian fashion house Dolce & Gabbana,

67

her hair was blonde and cropped closely to her head and round the ears, with a side-parting.

68

During the marching performance of „Holiday‟, Madonna acts out a military call and response routine, shouting orders with the backdrop of a huge

American flag, at a point intoning “My jock is loose, my pants are tight, my balls are swinging from left to right!” Both she and her dancers wear long, ceremonial, military greatcoats with epaulettes and big brassy buttons, that, when fanned out, reveal a red and white-striped lining that alludes to the backdrop.

69

The blue greatcoats with their insignia and the white and blue stripes of the T-shirts underneath point at the Navy (thus also forging a bond with Madonna‟s loyal gay audience).

If Madonna‟s close-cropped blonde garçonne hairdo is any indication, then we are back in the context of the interwar era.

70

But apart from any fetishist period and costume associations, the martial, retroZeitgeist of „Holiday‟ evokes the frank patriotism which carried Americans through

WW2, prior to an age of problematic wars starting with the one in Korea.

More than mere camp, it is a “calculated peek at American innocence,” 71

a chins-up patriotic mirror held to Clinton-era America, where the „American

Life‟ video then would be the disillusioned reverse reflection in that mirror of the Bush-era and developments leading up to Operation Iraqi Freedom.

5. 3 rd

aspect

This leads us over to the third and final aspect, that of the „ Ewig-

Weibliche ‟ power to draw on us, conjuring up admirable masculine qualities such as heroism and coaxing forth patriotism and civic virtue, typified by

8 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________

Kate Bush‟s 1979 „Tour of Life‟ stage performance of „Oh England My

Lionheart‟ 72

and by Madonna‟s 1990 TV-spot „Rock the Vote.‟

73

„Oh

England, My Lionheart‟ is sung „from the perspective of a dying World War

II British Spitfire pilot. Kate positions herself as a male character in order to tell the story, wearing an old, oversized flying jacket and „Biggles‟ air

74

„Oh helmet, the stage strewn with dying airmen and parachute traces.

England My Lionheart‟ displays a fascination with loss, death and departure, and this may provide a ground for her use of military motifs.

75

There is not the same sense as in „Army Dreamers‟ of this personal death as unnecessary.

Rather the death embodies that of a pure, genteel, chivalrous and heroic

England.

76

Another ground is Kate‟s infatuation with the heroism of soldiers:

“‟Lionheart‟ „sorta means hero, and I think hero is a very clichéd word, so I thought „Lionheart‟ would be a bit different.” 77

Even so, Kate Bush had later all but disowned „Oh England My Lionheart‟ as embarrassingly soppy: “It just makes me want to die. There‟s just something about that time...in 1979.”

Yes indeed, and it‟s that very „something‟ transcending her individual subjective awareness which arouses our curiosity. In disowning the piece,

Kate either hadn‟t realized or she had forgotten how the gently heroic tribute to a dying WW2 British Spitfire pilot was challenging the overly assertive patriarchal nationalism prevalent in late 1970‟s Britain.

78

In addition to which

„Lionheart‟ provided an English vibe as a counter to American pophegemony.

79

Vote‟ campaign.

Back in 1990, Madonna agreed to take part in the „Rock the

80

Rock the Vote‟s message is that politics could be „cool‟, that entertainment employing the free services of rock stars and celebrities is a way of „making real‟ the connection between young people‟s lives and public policy.

81

Madonna‟s presence in her „Rock the Vote‟ TV spot was part of an advertising campaign featured on MTV during the 1990 election season. She is in the centre of the frame, with two black male dancers, who stand behind and to the left and right of her, dressed in dark lace-up boots, navy blue shorts, and plain white T-shirts – a clear invocation of military costuming, and each waving a small flag. Madonna appears in a red bra and panties, a large American flag draped cape-like over her shoulders; she also wears military-style combat boots.

82

Of the clip it was said that: “[It] was timely, coming after intense debates on the sacredness of the flag.” 83

The performance and Madonna‟s lyrics: Dr King, Malcolm X, freedom of speech is as good as sex… Don‟t just sit there, let‟s go do it, speak your mind, there‟s nothing to it. Vote , and her parting salute – If you don‟t vote, you‟re gonna get a spankie – do seem satirical, so as to „Mock the Vote.‟

84

But, perhaps we are cynically misconstruing the video: Madonna‟s association of freedom of speech with sexual expression is in itself a demonstration of what freedom of speech entails.

85

She may be „bugging the squares‟, but is at the same time getting the message across in a manner to which young generation

Michael A. Langkjær 9

______________________________________________________________

X‟ers easily could relate. It may be just a coincidence that her patriotic starsand-stripes apparel has some resemblance to Wonder Woman, kombi sex object and superhero, and pop-cultural icon of empowered feminism in a

1976-79 weekly TV-series starring Lynda Carter that the X‟ers had grown up with.

86

6. Concluding remarks

So, is the bafflement any less? We have seen that Kate Bush and

Madonna shared vocal cross-gendering abilities that, along with their inherently manly being-in-control, had enabled them to straightforwardly partake of „rock military styled‟ masculinity. Their purposes for doing so – anti-war protest and critique of the military, attraction to military eroticism and phallicism, or a feminine device to recall or coax forth attractively masculine qualities such as heroism and patriotic civic virtue – were also shared. The different motifs had interplayed with cultural and political developments which had either made possible or restricted their new feminist empowerment claims – the latter being notably the case with Madonna‟s

„American Life‟ video. At all events, Kate Bush and Madonna made of the military style an especially potent, albeit risqué show of strength that was meant to liberate them from traditional female qualities and roles. Kate‟s and

Madonna‟s negative images of conflict, death and destruction as expressing perverse morbidity, gross aestheticism and a desire to disturb and shock, can also be seen in this light. The ironical attitude displayed by both women toward the military theme is tempered by a fundamental empathy, which probably springs from their shared attraction to „the male experience.‟

Despite the marked dissimilarities in their backgrounds, personalities and artistic temperaments, the fact that they do have so many points of similarity in their use of military style makes it possible to consider them as being typical of the larger group of female „glamazons of rock‟. It also encourages me in my view of the military-style of female performers as being more out-and-out ideologically motivated than we find it to be the case with their male rock military-styled compatriots.

Notes

1

M Rock, Picture This. Debbie Harry and Blondie , Sanctuary, London,

2004, pp. 234-235. Besides those female users of military style I have mentioned in the main text, there are (alphabetically): Neneh Cherry, Missy

Elliot, Bobbie Gentry, Janet Jackson, Cyndi Lauper, Avril Lavigne, Lisa

Lopez, Shirley Manson (of Garbage ), Morcheeba, Ambrosia Parsley (of

10 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________

Shivaree ), Ping Pong Bitches , Poison Girls , Juliet Simms, Britney Spears,

2 and Regina Spektor.

M A Langkjær, „“Then how can you explain Sgt. Pompous and the Fancy

Pants Club Band?” Utilization of Military Uniforms and Other Paraphernalia by Pop Groups and the Youth Counterculture in the 1960s and Subsequent

Periods‟, Textile History , Vol. 41, May 2010, Supplement: Textile History

3 and the Military , pp. 182-213.

D Mainon & J Ursini, The Modern Amazons. Warrior Women On-Screen,

4

Limelight Editions, Pompton Plains, New Jersey, 2006, pp. 2-3.

S Reynolds & J Press, The Sex Revolts. Gender, Rebellion and Rock‟n‟Roll ,

Serpent‟s Tail, London, 1995, p. 236.

5

Mainon & Ursini, Modern Amazons , p. 10; G Martin, „Dominatrix of the

Trade‟, NME , 3 October 1992, p. 32; Reynolds & Press, The Sex Revolts , p.

282; M Jones, Getting It On. The Clothing of Rock‟n‟Roll , Abbeville Press

Publishers, New York, 1987, pp. 14, 15, 149, 194, 196, mentions Madonna,

6 but without her gendered archetypes.

M Nicholls, „Among The Bushes‟, Record Mirror , 1980, retrieved on 5

June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i80_rm.html

: “[Bush:] I find the whole aggression of human beings fascinating – how we are suddenly whipped up to such an extent that we can‟t see anything except that;” J Solanas, „The

Barmy Dreamer‟, NME , 1983, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i83_nme1.html

: “you were covered in sweat and licking the barrel of a gun. I found it erotic but frightening, because it was so blatant;” L Brown, „The Story So Far‟, MuchMusic , May 30, 1987, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/iv87_mm2.html

: “A lot of your

7 songs and videos are filled with frightening or disquieting images.”

P Simper, „Dreamtime Is Over‟, Melody Maker , October 16, 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i82_mm.html

; R Smith, „Getting

Down Under With Kate Bush‟, 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i82_smi.html

; D Baker, „Wow, Wow, Wow,

Amazing, Amazing, Ama-ʼ, NME , October 20, 1979, retrieved on 5 June

2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i79_nme.html

: “Well, whenever I see the news, it‟s always the same depressing things. War‟s hostages and people‟s arms hanging off with all the tendons hanging out, you know. So I tend not to watch it much. I prefer to go and see a movie or something, where it‟s all put much more poetically. People getting their heads blown off in slow motion, very beautifully;” „What Kate Did Next‟, (from an unidentified UK magazine), 1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i85_what.html

: “I am fascinated by the negative aspects of terror. Isn‟t everyone? Horrible things fire my imagination.

Michael A. Langkjær 11

______________________________________________________________

Without them there‟d be no film industry. And tragic and scary things are

8 disturbing and powerful.”

S McClary, Feminine Endings. Music, Gender, and Sexuality , University of

Minnesota Press, Minnesota and Oxford, 1991 , p. 152, Mainon & Ursini,

9

Modern Amazons , pp. 5-8.

A Marvick, „The Women of Rock Interview‟, Women of Rock [a single issue magazine edited by A Marvick], 1984, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i84_wir.html

.

10

R M Mandziuk, „Feminist Politics & Postmodern Seductions: Madonna & the Struggle for Political Articulation‟, in C Schwichtenberg (ed.), The

Madonna Connection. Representational Politics, Subcultural Identities, and

Cultural Theory , Westview Press, Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford, 1993, p.

168.

11

A Sheffield, „The Kate Connection‟, Break-Through 5, 1983, retrieved on

5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i83_as.html

: “I‟m concerned with promoting the music. I‟m not really concerned with promoting me;” R Moy,

Kate Bush and „Hounds of Love‟ , Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington, 2007, pp. 6, 81-82; L Vrooman, „Kate Bush: Teen Pop and Older Female Fans‟, in

A Bennett & R A Peterson (eds.), Music Scenes. Local, Translocal, and

Virtual , Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville, 2004, p. 239; A Bennett,

„Consolidating the music scenes perspective‟, Poetics 32, 2004, p. 231; Moy,

Kate Bush , „Acknowledgements‟, notes that the Gaffaweb Kate Bush fan site is “a rich mine of information and sources;” M Cross, Madonna. A

Biography , Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut and London, 2007, pp.

77-84; C Benson & A Metz (eds.), The Madonna Companion. Two Decades of Commentary , Schirmer Books, New York, 1999, pp. 219-301; S Fouz-

Hernández & F Jarman-Ivens, „Re-invention? Madonna‟s drowned worlds resurface‟, in S Fouz-Hernández & F Jarman-Ivens (eds.), Madonna‟s

Drowned Worlds. New Approaches to her Cultural Transformations 1983-

2003 , Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington, 2004, p. xv; E A Kaplan,

„Madonna Politics: Perversion, Repression, or Subversion? Or Masks and/as

Master-y‟, in C Schwichtenberg (ed.), The Madonna Connection.

Representational Politics, Subcultural Identities, and Cultural Theory ,

Westview Press, Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford, 1993, p. 150.

12

Catherine (Kate) Bush was a self-taught poet and pianist from a musically talented family; fortunate enough to receive an inheritance and an EMI developmental contract at age 16 enabling her write songs, develop her musicianship and take dance and mime lessons; J Blake, „Sexy Kate Sings

Like An Angel‟, Evening News , February 18, 1978, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_en.html

; S Clarke, „Kate Bush City Limits‟,

NME , March 1978, retrieved on 5 June 2010,

12 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________ http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_nme.html

; „The Kate Inside‟, Superpop ,

February 10, 1979, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i79_sup.html

; J Juby, with K Sullivan, Kate Bush.

The Whole Story , Sidgewick & Jackson, London, 1988, p. 16; G Thomson,

Under the Ivy. The Life & Music of Kate Bush , Omnibus Press, London,

2010, p. 67.

13

S Albiez, „The day the music died laughing. Madonna and Country‟, in S

Fouz-Hernández & F Jarman-Ivens (eds.), Madonna‟s Drowned Worlds. New

Approaches to her Cultural Transformations, 1983-2003 , Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington, 2004, pp. 120, 121; L Phillips, „Girl on Film‟, NME , 8 th

August 1987, p. 14; G-C Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth. How One

Star‟s Self-Construction Rewrites Sex, Gender, Hollywood and the American

Dream , McFarland and Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina, and

London, 2002, pp. 2, 28-29, 147, 191: note 4.

14

15

Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth , p. 28.

R Rooksby, Madonna: the Complete Guide to her Music , Omnibus Press,

London etc., 2004, pp. 4-8; S Hawkins, „On performativity and production in

Madonna‟s „Music‟, in S Whiteley, A Bennett & S Hawkins (eds.), Music,

Space and Place. Popular Music and Cultural Identity , Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington, 2004, pp. 183, 190: note 8; J Kleinschmidt, „Kate Bush

„Hounds of Love‟ (1985)‟, Soundvenue magazine , nr. 31, 2009, pp. 100-101:

“queen of artpop;” E Gardner, „Kate Bush picks it up in „Aerial‟‟, USA

Today , 18 November 2005, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/iv05_usat.html

: “[Like] other quirky alt-pop darlings such as Bjork and Tori Amos;” G Quill, The Toronto Star , ‟Lost and Found‟,

5 November 2005, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/iv05ts01.html

: “darling of British prog-rock.”

16

A Blake, „Madonna the Musician‟, in F Lloyd (ed.), Deconstructing

Madonna , B.T. Batsford Ltd., London, 1993, pp.17-28; apparently so as to also follow the maturation of her audience.

17

Rooksby, Madonna: the Complete Guide , pp. 5-6; M Morton, „Don‟t Go for Second Sex, Baby!‟, in Schwichtenberg, The Madonna Connection , p.

223 quotes Madonna in K Sessums, „White Heat: Interview with Madonna‟,

Vanity Fair , April, 1990, p. 208; Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth , p.

22.

18

ʼThe Kick Inside‟, Press Release: EMI America, 1978, retrieved on 5 June

2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/im78_amp.html

; D M Withers, Adventures in

Kate Bush and Theory , HammerOn Press, Bristol, 2010, pp. 12, 45; P Kerton,

Kate Bush. An illustrated biography , Proteus, London and New York, 1980, p. 28 (quotes Bob Mercer); N Losseff, „Cathy‟s homecoming and the Other world: Kate Bush‟s „Wuthering Heights‟‟,

Popular Music , vol. 18/2, 1999, p.

Michael A. Langkjær 13

______________________________________________________________

229: “Kate Bush simply uses the vocal range normal for the average female voice” – the misleading impressions given by rock journalists who are not musicologists, like C Tomashoff, People Magazine , 24 January 1994, cited in

B Gordon, „Kate Bush‟s Subversive Shoes, Women & Music – A Journal of

Gender and Culture , vol. 9, 2005, printed from International Index to Music

Periodicals 05 June 2010, print view p. 3: “A key part of Bush‟s performance is her eerily versatile voice, which has an almost superhuman four-octave

[sic] range spanning from a deep tenor to an ultrahigh shriek.” But Losseff (p.

230) ends by admitting that “Kate Bush‟s exploration of vocal timbre and range is very wide.” E Wood, „Sapphonics‟, in P Brett, E Wood & G C

Thomas (eds.), Queering the Pitch. The New Gay and Lesbian Musicology ,

2 nd

edn., Routledge, New York and London, 2006, p. 28, 30; D Withers,

„Kate Bush: Performing and Creating Queer Subjectivities on Lionheart ‟,

Nebula , 3:2-3, September, 2006, pp. 127-128: “What perhaps gets missed however is how deep her voice can also go, how aggressive and macho this can be and how she can often slide between these two extreme pitches within a song...In Bush‟s voice alone, a case of sonic cross-dressing can be discerned, one that integrates both male and female – a vocal space that has the possibility of occupying a number of positions within a widened spectrum that stretches the two poles of the male/female binary.”

19

S Whiteley, Too Much Too Young. Popular Music, age and gender ,

Routledge, London and New York, 2005, p. 72.

20

Moy, Kate Bush , p. 86; K E Clifton, „Queer hearing and the Madonna queen‟, in S Fouz-Hernández & F Jarman-Ivens (eds.), Madonna‟s Drowned

Worlds. New Approaches to her Cultural Transformations, 1983-2003 ,

Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington, 2004, p. 59.

21

G Martin, „Non-Stop Erotica Cabaret‟, New Musical Express , 26

September 1992, p. 16; Martin, „Dominatrix of the Trade‟, p. 34.

22

Hawkins, „On performativity‟, pp. 180-190; Blake, „Madonna the

Musician‟, pp. 20, 22.

23

E Mayhew, „Positioning the producer: gender divisions in creative labour and value‟, in S Whiteley, A Bennett & S Hawkins (eds.), Music, Space and

Place. Popular Music and Cultural Identity , Ashgate, Aldershot and

Burlington, 2004, p. 149 (cites W Greckel, „Rock and Nineteenth-Century

Romanticism: Social and Cultural Parallels‟, Journal of Musicological

Research , vol. 3, issue 1, pp. 199-200), 151, 155-156; McClary, Feminine

Endings , p. 149; Hawkins, „On performativity‟, pp.181, 189: note 3; Moy,

Kate Bush , p. 83; E D Pribham, „Seduction, Control, & the Search for

Authenticity: Madonna‟s Truth or Dare ‟, in C Schwichtenberg (ed.), The

Madonna Connection. Representational Politics, Subcultural Identities, and

Cultural Theory , Westview Press, Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford, 1993, p.

14 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________

198; Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth , p. 184; Phillips, „Girl on

Film‟, p. 14. Kate‟s and Madonna‟s forays into male territory are also a postmodern, post-feminist self-definition against limitations of femininity with both pop star performers embodying Judith Butler‟s ideal post-modern, postfeminist gender-transcender; Kaplan, „Madonna Politics‟, p. 156; Guilbert,

Madonna as Postmodern Myth , p. 110; D Gauntlett, David, „Madonna‟s daughters. Girl power and the empowered girl-pop breakthrough‟, in S Fouz-

Hernández & F Jarman-Ivens (eds.), Madonna‟s Drowned Worlds. New

Approaches to her Cultural Transformations, 1983-2003 , Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington, 2004, p. 172.

24

Thomson, Under the Ivy , pp. 1, 92; Madonna in C Fisher, „Head Girl‟,

NME , 22 June 1991, p. 19; D Sinclair, „Dear Diary: The Secret World of

Kate Bush‟, Rolling Stone , February 24, 1994, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i94_rs.html

; Gordon, „Kate Bush‟s Subversive

Shoes‟, print view p. 3; Juby, Kate Bush , pp. 87-88; Mandziuk, „Feminist

Politics & Postmodern Seductions‟, p. 167; Pribram, „Seduction, Control, & the Search for Authenticity‟, pp. 195, 204.

25

R Jovanovic, Kate Bush. The Biography , Portrait/Platkus Books Ltd.,

London, 2005, p. 205; „Dreaming Debut‟, Radio 2, September 13, 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/ir82_r2.html

; Moy, Kate

Bush , p. 60; Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth , pp. 39, 112; M

Paytress, Bowiestyle , Omnibus Press, London, 2000, pp. 16, 69-79; M

Paytress, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars ,

(Classic Rock Albums, C. Heylin, series editor), Schirmer Books, New York,

1998, pp. 2-115.

26

J Izod, „Madonna as Trickster‟, in F Lloyd (ed.), Deconstructing Madonna ,

B.T. Batsford Ltd, London, 1993, pp. 49-56; Guilbert, Madonna as

Postmodern Myth , p. 36; Reynolds & Press, The Sex Revolts , pp. 232-234,

345-346; L Hyde, Trickster Makes This World. Mischief, Myth, and Art ,

North Point Press, New York, 1998. Like Madonna, Kate Bush is seen as quintessentially postmodern in the way she blurs genres and genders, with

Kate arguing that “there are probably twenty people in every individual;” H

Kruse, „Kate Bush. Enigmatic chanteuse as pop pioneer‟, Soundscapes.

Journal on media culture, vol. 3, November 2000 (originally published in

Tracking: Popular Music Studies , vol. 1, no. 1 (Spring, 1988), § 16; H Kruse,

„In Praise of Kate Bush – 1988‟, in S Frith & A Goodwin (eds.), On Record.

Rock, pop, and the written word , Pantheon Books, New York, 1990, p. 455;

Jovanovic, Kate Bush , p. 3.

27

Moy, Kate Bush , p. 30; K Needs, „Dream Time in the Bush‟, ZigZag , 1982, retrieved 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i82_zz.html

; K Bush, „About

Michael A. Langkjær 15

______________________________________________________________

The Dreaming‟, Kate‟s KBC article, Issue 12 (Oct. 1982), retrieved on 24

June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/kate14.html

; Jovanovic, Kate Bush , p. 137.

28

29

Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth , pp. 133, 145.

„Kate Bush: learning to sing and defying convention as she reaches for the heights‟, Radio & Record News , February 1978, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_rrn.html

; P Sutcliffe, „Labushka‟, Sounds ,

August 30, 1980, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i80_so.html

; R Boycott, „The Discreet Charm of

Kate Bush‟, Company , January 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i82_co.html

; Clarke, „Kate Bush City Limits‟; L-A

Jones, „Under The Burning Bush‟, You Magazine , October 22, 1989, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i89_you.html

; Bush in

Record Mirror , March 24, 1979, cited in Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 113; T

Lott, „Tete A Kate‟, Record Mirror , October 7, 1978, retrieved on 5 June

2010; H Doherty, „The Kick Outside‟, Melody Maker , June 3, 1978, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_mm2.html

; Reynolds & Press,

The Sex Revolts , pp. 240-241; „The Private Kate Bush‟, Hot Press , November

1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i85_hp.html

; T

Atkinson, „The Baffling, Alluring World of Kate Bush‟, January 28, 1990, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i90_la.html

; Kerton, Kate

Bush , p. 64; Whiteley, Too Much Too Young , pp. 9, 10; Juby, Kate Bush , pp.

86-87; Moy, Kate Bush , p. 74: “an implicit feminist.” M A Ellis, „Kate‟s

Fairy Tale‟, Record Mirror , February 25, 1978, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_rm.html

: “I want it to stand on the weight of my work, not what I look like;” Clarke, „Kate Bush City Limits‟: “I want to be recognized as an artist”; V Marriott, „Kate‟s Not Saying Too Much‟,

Newcastle Journal , January 16, 1979, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i79_nj.html

: “I used to wish I were a man, but now

I‟m happy to be a woman. I now believe that my looks don‟t get in the way of being accepted as a musician”; R Cook, „My music sophisticated? I‟d rather you said that than turdlike!‟, New Musical Express , October 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i82_nme.html

: “It‟s like

I‟ve had to prove that I‟m an artist inside a female body”; K Swayne, „Bushy

Tales‟, Kerrang!

, 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i82_ker.html

: “when I started there was really only me and Debbie Harry, and we got tied into the whole body thing. It was very flattering, but not the ideal image I would have chosen. Because people see that, rather than hear the songs.”

30

Reynolds & Press, The Sex Revolts , pp. 240-241; Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 90; Withers, „Kate Bush: Performing and Creating Queer Subjectivities‟, p.

125; M Dickie, „Woman‟s Work‟, Music Express (Can.), January 1990,

16 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________ retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i90_me.html

; Fisher,

„Head Girl‟, p. 19; Martin, „Non-Stop Erotica Cabaret‟, p. 17; Phillips, „Girl on Film‟, p. 14: “Somewhere deep down inside of me is a frustrated little boy”; M Rettenmund, „balls‟, Encyclopedia Madonnica , St. Martin‟s Press,

New York, 1995, pp. 15-16. Madonna‟s need to be tough may be due to a strict Catholic upbringing and a fraught relationship not only to her literal father but also the symbolic one: the Holy Father, the Law, and Patriarchy; M

St Michael, Madonna “Talking”. Madonna In Her Own Words , Omnibus

Press, London, 2004, pp. 8-13; B Johnston, „Confession of a Catholic Girl‟,

Interview magazine, 1989, in C Benson & A Metz (eds.), The Madonna

Companion. Two Decades of Commentary , Schirmer Books, New York,

1999, pp. 64ff; Kaplan, „Madonna Politics‟, p. 162; Rettenmund,

„Catholicism‟, Encyclopedia , p. 34; and her mother‟s death from breast cancer when the singer was six: D Eccleston, „Analyse this!‟, review of

American Life , Mojo , issue 114, May 2003, p. 86: “I made a vow that I would never need another person ever...turned my heart into a cage, a victim of a kind of rage.” Madonna has never advertised herself as disdainful of feminism: St Michael, Madonna “Talking” , pp. 81-84; Fouz-Hernández &

Jarmen-Ivens, „Re-invention?‟, p. xvii.

31

Gauntlett, „Madonna‟s Daughters‟, pp. 167-170; Guilbert, Madonna as

Postmodern Myth , pp. 24-25; C Schwichtenberg, „Madonna‟s Postmodern

Feminism: Bringing the Margins to the Center‟, in C Schwichtenberg (ed.),

The Madonna Connection. Representational Politics, Subcultural Identities, and Cultural Theory , Westview Press, Boulder, San Francisco, Oxford, 1993, p. 130.

32

Gauntlett, „Madonna‟s daughters‟, p. 162; Guilbert, Madonna as

Postmodern Myth , p. 3.

33

Little help is to be had in specialist studies of the uniform as a style-genre:

J Craik‟s Uniforms Exposed. From Conformity to Transgression , Berg,

Oxford and New York, 2005 passes Bush over, though there is a brief mention (p. 217) of Madonna‟s having “adopted a succession of looks” which included “a serious military phase.”

34

Kate Bush - Army Dreamers: Germany, RockPop live performance version, retrieved on 27 August 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HXt8xKA9Y_g&feature=related ; Kate

Bush - Army Dreamers: video, retrieved on 27 August 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tWdHOm256N4&feature=related ;

Madonna - „American Life‟, uncensored version, retrieved on 27 August

2010, http://il.youtube.com/watch?v=X1a35Fg_kBM&feature=related ; sanitized version, retrieved on 27 August 2010, http://il.youtube.com/watch?v=ehLuw0B_Ldo ; Re-Invention stage version,

Michael A. Langkjær 17

______________________________________________________________

2004, retrieved on 27 August 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PA0HiiRQ3us .

35

K Bush, „Them Bats and Doves‟, Kate‟s KBC article, Issue 7 (Sept. 1980), retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/kate8.html

; W R Creal,

„The Sensual World of Kate Bush‟, DISCoveries , February 1990, retrieved on

5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i90_d1.html

: “„Army Dreamers‟,

„Breathing‟ and „Experiment IV‟ – all songs that cast the military in an unfavorable light.”

36

On the sleeve of the „Army Dreamers‟ single mix, Kate Bush wears an overseas cap, in R Godwin, The Illustrated Collector‟s Guide to Kate Bush ,

2 nd

edn., Collector‟s Guide Ltd, Burlington, Ontario, 2005, p. 33.

37

“We decided a cleaning-woman [whom Kate called “Mrs Mopp”] of abstract barracks would be fine, joined by three army dreamers, one of whom is a mad sergeant-major who shouts commands at invisible troops, one who carries a gun and mandolin, and one who blinks blankly and carries a small brown teddy bear... I wanted the mother to be a very simple woman who‟s obviously got a lot of work to do. She‟s full of remorse, but she has to carry on, living in a dream;” K Bush, „“December will be magic again”‟, Kate‟s

KBC article, Issue 8 (December 1980), retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/kate9.html

; K Bush, „Week-long Diary‟, The

Complete published writings of Kate Bush, retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/flexipop.html

. A somewhat different version of „Army

Dreamers‟ was done in Holland; see P Bush, „Memoirs of an Army

Dreamer‟, Paddy‟s Fourth KBC article, Issue 8, Christmas 1980, retrieved on

24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/paddy4.html

; P Bush, „Gateway to the

Firmament‟, Paddy‟s Twelfth KBC article, Kate Bush Newsletter, Issue 19,

Christmas 1985, retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/paddy12.html

.

38

C Irwin, „Paranoia and Passion of the Kate Inside‟, Melody Maker , October

4, 1980, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i80_mm.html

.

39

Kate was able to develop this sound symbolism by pioneering use of a

Fairlight CMI (Computerized Musical Instrument) synthesizer; Juby, Kate

Bush , p. 60; K Cann & S Mayes, Kate Bush. A Visual Documentary ,

Omnibus Press, London, 1988, p. 52; Moy, Kate Bush , p. 78; Thomson,

Under the Ivy , pp. 4, 164-165.

40

Cann & Mayes, Kate Bush , p. 75. Produced from a storyboard sketched by

Kate Bush herself inspired by “every war movie [she‟d] ever seen, from All

Quiet on the Western Front to Apocalypse Now ;” Jovanovic, Kate Bush , p.

124; Bush, „“December will be magic again”‟: “We wanted a very violent movement of my body, ideally being thrown off the ground. The effect we used was the jerk-jacket, which we would film and then put into slow motion

18 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________ at the editing stage. The jacket consists of a harness and a wire, with a man manually pulling the wire via a pulley system. The wire is connected to the back of the harness, with a hole through various layers of clothing to allow the wire to be straight when taught. As the man pulls the wire, the person wearing the harness is pulled off their feet backwards, landing on an appropriately camouflaged, padded area to soften the landing.”

41

Dismissal of what some saw as Kate‟s disengaged, uninformed, pampered rich girl „spaceyness‟ and inconsequential song themes may have given her pause, persuading her to release „Army Dreamers‟; Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 170; H Doherty, „Bush Baby‟, Melody Maker , March 1978, retrieved on 5

June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_mm1.html

; R Denyer, „The Kate

Gallery‟, Sound International , September 1980, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i80_si.html

; Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 169, quotes

Bush (in K Needs, „Fire in the Bush‟, ZigZag , 1980(?)): “But it‟s only because the political motivations move me emotionally. If they hadn‟t, it wouldn‟t have gotten to me. It went through the emotional centre, when I thought, „Ah, Ow!” And that made me write;” „Dreaming Debut‟, Radio 2,

September 13, 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/ir82_r2.html

; C Heath, ?, Fall 1985, retrieved on 5

June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i85_ch.html

; „The New Music (TV) about The Dreaming‟, August 3/4 1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/iv82_nm.html

: “I never felt that I‟ve written from a political point of view. It‟s always been an emotional point of view that just happens to perhaps be a political situation. I mean war is an extremely emotional situation, especially if you‟re going to be blown up!;” J Diliburto,

Totally Wired/Songwriter/Keyboard , 1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/ir85_tw.html

; B Fishkind, „Is Kate Bush News To

You?‟, The Island Ear , January 7, 1986, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i86_ie.html

; J Long, „Interview with Kate Bush for

Greater London Radio‟, 12-13 October 1989, retrieved 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/ir89_gl.html

; „The VH-1 [TV] interview‟, January

1990, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/iv90_vh1.html

.

Lyrically the songs in Kate Bush‟s album Never For Ever were notable less for their political content than for her continued determination to be “reject and subvert conventional gender roles” and be “attuned to her own

„masculinity‟ as an artist;” Thomson, Under the Ivy , pp. 172-173; Withers,

Kate Bush and Theory , pp. 73-74: “This transformation occurs to [Bush‟s] voice – it becomes politicised and more engaged with the world.”

42

She sang „Army Dreamers‟ with a semi-Irish accent, which led Colin Irwin

(„Paranoia and Passion of the Kate Inside‟) to comment: “Kate has an enormous number of relatives in Ireland, and she‟s fearful of the Irish

Michael A. Langkjær 19

______________________________________________________________ reaction to „Army Dreamers‟...Ireland isn‟t mentioned in the song, and she inserted a reference to BFPO [British Offices Post Office] to divert attention.” Kate put out a disclaimer („NfE Interview‟, EMI London, 1980, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/im80_nf2.html

; K Needs,

„Fire in the Bush‟, ZigZag , 1980(?), retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i80_zz.html

): “It‟s not actually directed at Ireland.

It‟s included, but it‟s much more embracing the whole European thing…the song was meant to cover areas like Germany, especially with the kids that get killed in manoeuvres, not even in action. It doesn‟t get brought out much, but it happens a lot...That‟s why it says BFPO in the first chorus, to try and broaden it away from Ireland...The Irish accent was important because...the

Irish would always use their songs to tell stories, it‟s the traditional way.

There‟s something about an Irish accent that‟s very vulnerable, very poetic, and so by singing it in an Irish accent it comes across in a different way.”

Even so, when pressed about her impression of the relationship between the

English and the Irish („The Private Kate Bush‟), Kate replied: “people being bombed and shot, and a very military kind of scene with lots of repression and perhaps the English not being too welcome there.”

43

„Wikipedia - American Life‟, retrieved on 6 June 2010, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Life : A concept album, with recurring themes of „American Dream‟ and „materialism‟ with French design team

M/M Paris (Michael Amzalag and Mathias Augustyniak) responsible for the sleeve-artwork; in mid-January 2003, in Los Angeles, the photo shoot for the album was done by photographer Craig McDean. P Rees, „“I used to be an idiot”‟, pp. 138-143, and L O‟Brien, „Essential Madonna‟ (review of

American Life ), pp. 128-129, both in Q Special Edition , „At home and in bed with Madonna: Madonna 20 th

Anniversary Collector‟s Edition‟, editor-inchief: P Alexander, Q/Mappin House, London, 2003.

44

O‟Brien, Madonna , p. 269; H Charlton, „Introduction‟, pp. 7-14 in T Ziff

(ed.), Che Guevara: Revolutionary Icon , V&A Publications, London, 2006, and p. 82: “Madonna‟s reinvention of her own image plays purposefully with the historic image of „Tania‟, the nom de guerre of Haydee Tamara Bunke

Bider, who died in a 1967 ambush in Bolivia at the age of 29… In the best known photograph of Tania, she is wearing the same type of beret as Che

Guevara…The „Tania‟ image was echoed and referenced in the 1974 image of newspaper heiress Patty Hearst, who took on the name of „Tania‟ while active in the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA);” M Casey, Che‟s Afterlife.

The Legacy of an Image , Vintage Books, New York, 2009, p. 42-43, 44;

Rooksby, Madonna: the Complete Guide , p. 61. Possibly, it was the Irish folk artist Jim Fitzpatrick‟s famous poster of May 1968 based on the Korda photo and with a black and white toned Che on red background that had furnished

20 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________ the template, especially evident in the promo-poster for „American Life‟; see

Casey, Che‟s Afterlife , pp. 120-125, illus. Betw. pp. 244 and 245.

45

Rees „“I used to be an idiot”‟, p. 142; O‟Brien, Madonna , p. 272: she and her French techno musician co-producer and co-writer on American Life

Mirwais Ahmadzaï “both got sucked into the French existentialist vortex. We both decided we were against the war, and we both smoked Gauloises and wore berets, and we were against everything...I was in a very angry mood, a mood to be political, very upset with George Bush.”

46

Ziff, Che Guevara , p. 82; „Wikipedia - American Life‟, retrieved on 8

August 2010, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:American_Life_(single).jpg

; also printed on the cover of the April 29 1974 edition of Newsweek . See also

NME , 29 March 2003, p. 8.

47

Accompanying Rees, „“I used to be an idiot”‟ (interview, May 2003), in Q

Special Edition , pp. 138-143.

48

H Keazor & T Wübbena, Video Thrills the Radio Star. Musikvideos:

Geschichte, Themen, Analysen , transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, 2005, p. 152;

O‟Brien, Madonna , p. 269.

49

Shot in February 2003 by Swedish director Jonas Akerlund, „American

Life‟ with song lyrics, written and produced by Madonna and Paris based record producer and songwriter Mirwais Ahmadzaï;

DrudgeReportArchives.com, „Madonna 2003 American Life‟, retrieved on 8

August 2010, http://www.drudgereportarchives.com/data/2003/04/01/20030401_062052_m ad.htm

.

50

Actually, there were several endings filmed. The Director‟s Cut version ends with the live grenade simply landing on the catwalk; „Youtube:

Madonna American Life Director‟s Cut (Official First Video)‟, retrieved on 7

August 2010, http://il.youtube.com/watch?v=MtPNOxtHbNM .

51

J Wiederhorn, „Madonna Defends Her Violent „American Life‟ Video.

Singer says she honours her country by expressing her feelings‟, MTV

Networks , Artist Pages: Madonna, February 14 2003, retrieved on 8 August

2010, http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1469995/20030214/madonna.jhtml

;

DrudgeReportArchives.com, „Drudge Report, Mon. March 31, 2003,

MADONNA PULLS NEW SHOCK VIDEO IN USA; SCENES OF

TRANSVESTITE SOLDIERS, GRENADE THROWN AT BUSH; DEBUTS

IN GERMANY‟, retrieved 8 August 2010, http://www.drudgereportarchives.com/data/2003/04/01/20030401_062052_m ad3.htm

; J Wiederhorn, with additional reporting by J Norris, „Madonna

Yanks Controversial „American Life‟ Video. Madonna says she originally wanted the video to convey strong anti-war, anti-materialism, anti-fashion

Michael A. Langkjær 21

______________________________________________________________ industry statements‟, MTV Networks , March 31, 2003, retrieved on 8 August

2010, http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1470876/20030331/madonna.jhtml

.

52

D Voller, „Style Wars‟, Q Special Edition , „At home and in bed with

Madonna: Madonna 20 th

Anniversary Collector‟s Edition‟, editor-in-chief: P

Alexander, Q/Mappin House, London, 2003, p. 91; O‟Brien, Madonna , p. 4:

“in the wake of the 2003 Iraq War, Madonna vas vocal in her opposition to

George Bush, urging her fans to go and see Michael Moore‟s controversial documentary Fahrenheit 9/11 .”

53

O‟Brien, Madonna , pp. 270-271;„Protect Yourself‟, Newsweek , April 2,

2003: “After all, as the Dixie Chicks proved, if you express yourself, you have to be prepared to protect yourself;” J Oppelaar, „Musicians Wage War of Songs‟, Variety , Apr. 7-Apr. 13, 2003, p. 19; D Philadelphia, „The Perils of Protest‟, Time , Monday, Apr. 14, 2003, retrieved on 7 August 2010, http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1004659,00.html

; NME ,

12 April 2003, p. 12; J Eliscu, „Rock & Roll: War on Protest: Artists Struggle

Against the Media and Fans To Get Their Anti-War Message Out‟, Rolling

Stone , 1 May 2003, pp. 9-10; St Michael, Madonna “Talking” , p. 68.

54

Albiez, „The day the music died laughing‟, p. 124; St Michael, Madonna

“Talking” , p. 90. For the stage performance of „American Life‟ during the

2004 Re-Invention Tour, the dancers in army gear did a drill while the sounds of helicopters and bombs were heard and the screens displayed images of fighting soldiers and wounded children in time of war. Madonna then appeared on stage in army gear and a black beret. At the end, the video screen shows a Bush lookalike laying his head on the shoulder of a Saddam double.

Also here, the war symbolism was much discussed and criticised; B

Vanmaele, „American Life – Mad-Eyes – Madonna single lyrics, Jonas

Akerlund video, military…‟; YouTube, „Madonna American Life Re

Invention Tour‟, retrieved on 7 August 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=637fZgKWOp4 ; O‟Brien, Madonna , pp.

278-279.

55

Vanmaele, „American Life – Mad-Eyes‟; Keazor & Wübbena, Video

Thrills the Radio Star , p. 146, and note 36.

56

Mainon & Ursini, Modern Amazons , pp. 272-277; K Adie, Corsets to

Camouflage. Women and War , Hodder & Stoughton/Imperial War Musuem,

London, 2003, pp. 211-241.

57

YouTube, „Kate Bush/10 of 12/James & the Cold Gun – Live at

Hammersmith Odeon 1979‟, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GtnXAPIMh5w&feature=related ;

YouTube, „Babooshka – Kate

Bush‟, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ot3cVY1JESQ ; YouTube, „14.

Holiday – The Girlie Show‟,

22 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FaPCSYAwkcw&feature=related , all retrieved on 27 August 2010.

58

Juby, Kate Bush , p. 28; Moy, Kate Bush , p. 13; Withers, Kate Bush and

Theory , pp. 19-20. In the spring of 1979, Kate Bush had embarked upon her concert tour, the „Tour of Life‟, a 2½ hour spectacle featuring numerous costume changes, elaborate staging and choreography - a totally theatrical experience unlike the usual rock and pop shows of her contemporaries;

Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 122; „She‟s Your No. 1‟, Rock and Pop Stars,

1979, # 1 from EMI‟s promotional magazine, 1979, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i79_rps.html

; Moy, Kate Bush , p. 2; Myskow,

„Wow! Wow! It‟s Raunchy Kate‟, The Sun , May(?), 1979, retrieved on 5

June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i79_ts.html

; Cann & Mayes, Kate Bush.

A Visual Documentary , p. 40; Vrooman, „Kate Bush: Teen Pop and Older

Female Fans‟, p. 239; Withers, „Kate Bush: Performing and Creating Queer

Subjectivities‟, p. 126; Juby, Kate Bush , p. 54; Kruse, „Enigmatic chanteuse‟,

§ 19; Kruse, „In Praise of Kate Bush‟, p. 456.

59

Kate‟s cowboy costume is also seen on sleeves of „Kate Bush On Stage‟

12” EPs (Mini LP‟s), reproduced in Godwin, The Illustrated Collector‟s

Guide to Kate Bush , pp. 12, 41.

60

D Palmer in Homeground , Summer 2007, quoted in Thomson, Under the

Ivy , p. 75: “The Wild West theme was a hangover from her pub performances of the same song in 1977, where she had dressed up as a cowgirl” and “She‟d go around shooting people;” Kerton,

Kate Bush , p. 95; Jovanovic, Kate Bush , p. 101.

61

Sutcliffe, „Labushka‟; Irwin, „Paranoia and Passion‟; Thomson, Under the

Ivy , p. 138: “On the final night of the tour, instead of Bush facing off against just Paddy and the dancers, the entire stage crew dressed up as cowboys and

Indians and by the time the scene finished Bush was knee deep in „corpses‟ and red liquid.”

62

D Laing, One Chord Wonders. Power and Meaning in Punk Rock , Open

University Press, Milton Keynes and Philadelphia, 1985, p. 87; Bush in

Sounds , August 30, 1980, in Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 160. In the picture sleeve of the single album Running Up That Hill Kate is aiming a bow;

Godwin, The Illustrated Collector‟s Guide to Kate Bush , pp. 37, 44; Melody

Maker , 24 August 1985 (excerpts), 1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i85_mm1.html

; T Nico, „Fairy Tales & Nursery

Rhymes‟, Melody Maker , August 24, 1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i85_mm2.html

. The most archetypically female weapon for women in action films is the bow and arrow; Mainon & Ursini,

Modern Amazons , p. 14; J Shelley, „Wow! (Revisited)‟, Blitz , September

1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i85_bl.html

. During

Michael A. Langkjær 23

______________________________________________________________ the Who‟s That Girl?tour, in Italy, Madonna sings that song in front of a large board of Cagney with a machine gun. She plays with a revolver and there are gunfire noises; Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth , pp. 77-78,

80: “Further playing with the notion of dick, Madonna later takes hold of

Dick‟s [Dick Tracy‟s] revolver, shoots in the air, and blows on the barrel.”

63

C Bolton (ed.), Kate Bush Complete , EMI Music Publishing Ltd., London,

1987, p. 27; Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 162; Cann & Mayes, Kate Bush. A

Visual Documentary , p. 56; Jovanovic, Kate Bush , p. 114.

64

The Babooshka „Xena‟- costume is depicted on the sleeve of an

American/Canadian „Kate Bush‟ mini LP, and Japanese/UK „The Single File‟

CDV in Godwin, The Illustrated Collectors Guide to Kate Bush , pp. 12, 23, a

UK bootleg gatefold, p. 65, and a UK/Japan „The Single File‟ video tape cover, p. 80; Mainon & Ursini, Modern Amazons , pp. 51-52.

65

66

Withers, Kate Bush and Theory , p. 73; Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 263.

Mainon & Ursini, Modern Amazons , pp 35-37, 63. In her Aerial album from 2005, Kate sings in „Joanni‟ about Joan of Arc without a ring on her finger and wearing bright armour, which may well have been inspired by two recent Joan of Arc filmatisations: Luc Besson‟s 1999 The Messenger with

Milla Jovovich as an actively battling Joan and the 1999 TV miniseries on

Joan‟s life starring LeeLee Sobieski.

67

Rettenmund, „Girlie Show tour, The‟; Encyclopedia , pp. 73-75; idem.,„Dolce & Gabbana‟, Encyclopedia , p. 52.

68

„The Girlie Show‟ that opened in London on September 25, 1993 was launched in support of Madonna‟s 1992 album, Erotica . C Clerk,

Madonnastyle , Omnibus Press, London, 2002, p. 119.

69

70

Albiez, „The day the music died laughing‟, p. 123.

R Corliss, „Madonna Goes to Camp‟, Time magazine, October 25, 1993, in

C Benson & A Metz (eds.), The Madonna Companion. Two Decades of

Commentary , Schirmer Books, New York, 1999, p. 22; „The Girlie Show

Tour‟, madonna-online.ch (fansite), retrieved on 3 September 2010, http://www.madonna-online.ch/m-online/tours/93_gs/facts/girlie-facts.htm

.

71

72

Corliss, „Madonna Goes to Camp‟, p. 22.

„1979, Tour of Life, Live at Hammersmith Odeon‟, retrieved on 27 August

2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xakoLYwokBo .

73

„1990 Rock the Vote ad‟, retrieved on 27 August 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DSM9eLptGsY&feature=related .

74

Thomson, Under the Ivy , p. 138: “The set was inspired by old war films like A Matter of Life and Death and Reach for the Sky ;” C Ward (?),

„MuchMusic (TV)‟, November 1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/iv85_ca1.html

; Cann & Mayes, Kate Bush. A Visual

Documentary , p. 45; Withers, Kate Bush and Theory , p. 58. In the video for

24 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________

„The Big Sky‟, Kate performs surrounded by airmen or „high flyers‟ of all nationalities and eras; YouTube, „Kate Bush – The Big Sky‟, retrieved on 27

August 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hhyqhm06-X4 .

75

76

Withers, Kate Bush and Theory , p. 58.

M Bracewell, England is Mine. Pop Life in Albion from Wilde to Goldie ,

HarperCollins, London, 1997, pp. 160-161; Kerton, Kate Bush , p. 73;

Jovanovic, Kate Bush , p. 9; Kate Bush quoted in Lionheart Promo Cassette,

EMI Canada (interviewer unknown), 1978, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/im78_lh.html

; Withers, Kate Bush and Theory , pp.

57, 59. See also D Cannadine, Ornamentalism. How the British Saw Their

Empire , Allen Lane/The Penguin Press, London, 2001, pp. 181-99.

77

78

Withers, Kate Bush and Theory , pp. 58-59.

79

Moy, Kate Bush , p. 55; Withers, Kate Bush and Theory , p. 61.

M Mehler, „Bush Is A Sex Kitten‟, (American?), 1978, retrieved on 5 June

2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/‟78_sex.html

; P Swales, Musician (unedited),

Fall 1985, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i85_swa.html

;

R Moy, „A Daughter of Albion. Kate Bush and mythologies of Englishness‟,

Popular Musicology Online , retrieved on 6 June 2010, http://www.popularmusicology-online.com/issues/02/moy-01.html

, printout p. 2: “Essentially, I am interested in how Kate Bush‟s music stands in relation to the power of the

North American mainstream, and the way that many aspects of her recordings subvert these globalised musical values.”

80

81

Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth , p. 90.

„Generation X‟ comprises those born 1965-1977. M Hoover & S Orr,

„Youth Political Engagement: Why Rock the Vote Hits the Wrong Note‟, in

D M Shea & J C Green (eds.), Fountain of Youth. Strategies and Tactics for

Mobilizing America‟s Young Voters , Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.,

Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Plymouth, UK, 2007, pp. 142, 144,

147-149, 156, 158, 160: note 5; S Assael, „Mock the Vote. Proponents of voter drive fail to cast own ballots‟, Rolling Stone , January 24, 1991, n.p.;

Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth , p. 90: “Apparently she started voting in the nineties.”

82

C Andersen, Madonna unauthorized , Island Books, New York, 1991, illustration between pp. 186 and 187.

83

84

Rettenmund, „Rock the Vote‟, Encyclopedia , p. 150.

Albiez, „The day the music died laughing‟, pp. 122, 129; Mandziuk,

„Feminist Politics‟, p. 174.

85

Mandziuk, „Feminist Politics‟, p. 180.

86

Mainon & Ursini, Modern Amazons , pp. 112-117.

Michael A. Langkjær 25

______________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Adie, K., Corsets to Camouflage. Women and War , Hodder &

Stoughton/Imperial War Musuem, London, 2003.

Albiez, S., „The day the music died laughing. Madonna and Country‟, in

Santiago Fouz-Hernández & Freya Jarman-Ivens (eds.),

Madonna‟s Drowned

Worlds. New Approaches to her Cultural Transformations, 1983-2003 ,

Ashgate, Aldershot and Burlington, 2004, p. 120.

Andersen, C., Madonna unauthorized , Island Books, New York, 1991.

Assael, S., „Mock the Vote. Proponents of voter drive fail to cast own ballots‟,

Rolling Stone , January 24, 1991, n.p.

Atkinson, T., „The Baffling, Alluring World of Kate Bush‟, January 28, 1990, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i90_la.html

.

Baker, D., „Wow, Wow, Wow, Amazing, Amazing, Ama-„,

New Musical

Express , October 20, 1979, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i79_nme.html

.

Bennett, A., „Consolidating the music scenes perspective‟, Poetics 32, 2004, p. 231.

Benson, C., & A. Metz (eds.), The Madonna Companion. Two Decades of

Commentary , Schirmer Books, New York, 1999.

„Big Sky, The‟, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hhyqhm06-X4 .

Blake, A., „Madonna the Musician‟, in Fran Lloyd (ed.), Deconstructing

Madonna , B.T. Batsford Ltd., London, 1993, pp.17-28.

Blake, J., „Sexy Kate Sings Like An Angel‟,

Evening News , February 18,

1978, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_en.html

.

Bolton, C., (ed.), Kate Bush Complete , EMI Music Publishing Ltd., London,

1987.

26 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________

Boycott, R., „The Discreet Charm of Kate Bush‟, Company , January 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i82_co.html

.

Bracewell, M., England is Mine. Pop Life in Albion from Wilde to Goldie ,

HarperCollins, London, 1997.

Brown, L., „The Story So Far‟, MuchMusic , May 30, 1987, retrieved on 5

June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/iv87_mm2.html

.

Bush, K., “About The Dreaming”, Kate‟s KBC article, Issue 12 (Oct. 1982), retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/kate14.html

.

Bush, K., “December will be magic again”, Kate‟s KBC article, Issue 8

(December 1980), retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/kate9.html

.

Bush, K., “Them Bats and Doves”, Kate‟s KBC article, Issue 7 (Sept. 1980), retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/kate8.html

.

Bush, K., „Week-long Diary‟, The Complete published writings of Kate

Bush, retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/flexipop.html

.

Bush, P., „Memoirs of an Army Dreamer‟, Paddy‟s Fourth KBC article, Issue

8, Christmas 1980, retrieved on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/paddy4.html

.

Bush, P., „Gateway to the Firmament‟, Paddy‟s Twelfth KBC article, Kate

Bush Newsletter, Issue 19, Christmas 1985, retrived on 24 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/garden/paddy12.html

.

Cann, K. & S. Mayes, Kate Bush. A Visual Documentary , Omnibus Press,

London, 1988.

Cannadine, D., Ornamentalism. How the British Saw Their Empire , Allen

Lane/The Penguin Press, London, 2001.

Casey, M., Che‟s Afterlife. The Legacy of an Image , Vintage Books, New

York, 2009.

Charlton, H., „Introduction‟, in T Ziff (ed.), Che Guevara: Revolutionary

Icon , V&A Publications,London, 2006, pp. 7-14.

Michael A. Langkjær 27

______________________________________________________________

Clarke, S., „Kate Bush City Limits‟, New Musical Express , March 1978, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_nme.html

.

Clerk, C., Madonnastyle , Omnibus Press, London, 2002.

Clifton, K. E., „Queer hearing and the Madonna queen‟, in Santiago Fouz-

Hernández & Freya Jarman-Ivens (eds.), Madonna‟s Drowned Worlds. New

Approaches to her Cultural Transformations, 1983-2003 , Ashgate,

Aldershot and Burlington, 2004, p. 55.

Cook, R., „My music sophisticated? I‟d rather you said that than turdlike!‟,

New Musical Express , October 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i82_nme.html

.

Corliss, R., „Madonna Goes to Camp‟, Time magazine, October 25, 1993, in

Carol Benson & Allan Metz (eds.), The Madonna Companion. Two Decades of Commentary , Schirmer Books, New York, 1999, pp. 21-22.

Craik, J., Uniforms Exposed. From Conformity to Transgression , Berg,

Oxford and New York, 2005.

Creal, W. R., „The Sensual World of Kate Bush‟, DISCoveries , February

1990, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i90_d1.html

.

Cross, M., Madonna. A Biography , Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut and London, 2007.

Denyer, R., „The Kate Gallery‟, Sound International , September 1980, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i80_si.html

.

Dickie, M., „Woman‟s Work‟, Music Express (Can.), January 1990, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i90_me.html

.

Diliburto, J., Totally Wired/Songwriter/Keyboard , 1985, retrieved on 5 June

2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/ir85_tw.html

.

Doherty, H., „Bush Baby‟, Melody Maker , March 1978, retrieved on 5 June

2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_mm1.html

.

28 „Glamazons‟ of Pop

______________________________________________________________

Doherty, H., „The Kick Outside‟, Melody Maker , June 3, 1978, retrieved on 5

June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/i78_mm2.html

.

„Dreaming Debut‟, Radio 2, September 13, 1982, retrieved on 5 June 2010, http://gaffa.org/reaching/ir82_r2.html

.