the petition here - Bagong Alyansang Makabayan

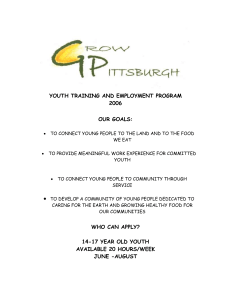

advertisement