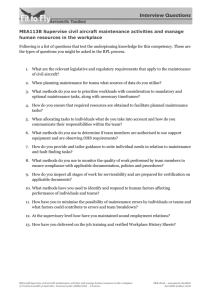

Air Movements Training and Development Unit

advertisement

Presentation of the Governor-General’s Banner Air Movements Training and Development Unit Presentation of the Governor-General’s Banner to AMTDU On 15 May 2014, Air Movements Training and Development Unit (AMTDU) will be presented with its Governor-General’s Banner during a parade and ceremony at RAAF Base Richmond. The Governor-General, His Excellency General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK, MC (Retd), will be present for the Banner’s consecration by Air Force Chaplains and its presentation to AMTDU. The Governor-General’s Banner is presented to an Air Force unit with at least 25 years of service that is considered to be non-operational. Units which are operational are presented with a Squadron Standard. AMTDU was established in 1965, and despite its ‘non-operational’ status, is routinely involved with day-to-day operations of the Australian Defence Force, as well as training of personnel and development of new loads for Defence. The origins of military Banners, Standards and other ‘Colours’ extends back to when armies would carry banners on battlefields for the purposes of identification. These acted as a marker for unit commanders and a ‘rallying point’ for their personnel. The practice of unit banners extended through to the medieval times to the British Commonwealth, and adopted by the Royal Australian Air Force shortly after its formation in 1921. A Governor-General’s Banner is an important part of Air Force culture and tradition. They are displayed and presented during formal parades, marches, dining-in nights and other special events. They are otherwise kept on display within the unit’s Headquarters, and in keeping with its ancient traditions, remain a ‘rallying point’ for AMTDU personnel who are deployed away on tasks. 2 About AMTDU Air Movements Training and Development Unit (AMTDU) is located at RAAF Base Richmond, and comes under the direct command of Headquarters Air Mobility Group, Royal Australian Air Force. It is comprised of 63 personnel - 31 RAAF (including four reservists), 25 Army, and 10 Australian Public Servants. AMTDU has two primary roles: The development of load carrying tech- niques for equipment which is required for air transport and/or airborne delivery by a Defence aircraft. Training of airload and air dispatch tech- niques to Defence personnel, typically comprised of Army Air Logistics personnel and Air Force air movements students from the RAAF School of Administration and Logistics Training (RAAFSALT). [Above] The AMTDU crest. The Pegasus signifies the unit’s focus on providing air mobility support to the wider Australian Defence Force, with the crossed torches signifying the unit’s focus on knowledge and learning. While these roles focus on providing a trained workforce and information for the wider Australian Defence Force, AMTDU is often called upon to deploy expert personnel to provide first hand support to operations. The AMTDU internal structure is as follows: Aerial Delivery Development Flight: Con- ducts the clearances of loads, develops procedures and provides advice regarding transport of cargo by all Defence aircraft. Aerospace Systems Development Flight: Provides support to Air Mobility Group Operational Test and Evaluation programs, and airworthiness management. Army Training and Air Force Training: Army Training provide Air Logistics training to Defence personnel. Air Force Training 3 [Above] Australia’s expertise in the field of air movements builds on more than 70 years of experience in war-like and peacetime operations. Over this time, the Australian Defence Force has employed a variety of transport aircraft across Australia as well as into the South West Pacific, South East Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. has transitioned to the command of the RAAFSALT, however this air movements work is still largely conducted from RAAF Base Richmond. HQ and ADMIN: Provides command, ad- ministration, and personnel capability services. AMTDU’s development work is also conducted for ‘one off’ or rarely carried loads. In many cases however, AMTDU will produce load diagrams for frequently carried cargo, which then act as an instruction for ADF personnel on how to carry these loads safely in future. AMTDU also has a responsibility for engaging with Army Air Logistics personnel, and Air Force Air Movements personnel (via RAAFSALT), to teach the correct practice of aircraft loading and air dispatch. [Above] RAAF Air Movements Sections are located at bases across Australia, as well as in deployed locations in the Middle East Area of Operations and in Malaysia. During short-notice operations, Mobile Air Load Teams are the first to deploy and last to leave from a location. Air Force’s Air Movements personnel are trained by RAAF School of Administration and Logistics Training staff, utilising facilities and devices at AMTDU at RAAF Base Richmond. AMTDU consults extensively with foreign military counterparts, including training and development organisations within the United States Air Force, American Army, Royal Air Force, and Royal New Zealand Air Force. The AMTDU workforce is made up primarily of Aeronautical Engineers, Loadmasters, Army Aircrew and Air Dispatchers. [Above] Army Air Dispatch personnel are often required to prepare loads for external carriage by helicopter, as well as for internal carriage (and airdrop) by a fixed-wing aircraft. Its staff also includes Pilots and Air Combat Officers; Personnel Capability Officers/ Specialists; Logistics Officers; and other support personnel. In March 2014, AMTDU was awarded the Markowski Cup under the annual Air Force Awards. The Markowski Cup is presented annually for Air Force’s most proficient non-flying unit. [Above] Members of AMTDU with the Markowski Cup in March 2014, recognising its achievement as Air Force’s most proficient non-flying unit. 4 The Hardware One of the key requirements for the Australian Defence Force is the ability to deploy over a long distance quickly, and field its equipment safely and effectively. To accomplish this task, the Australian Defence Force has a range of fixed-wing and rotary-wing transports that can carry a variety of payloads. Air Force has a fleet of 12 C-130J Hercules for the medium tactical airlift role, which have a cargo bay which can accommodate up to 20 tonnes of cargo. The fleet of six C-17A Globemaster III transports are much larger in size, and are able to accommodate up to 70 tonnes. Both the Hercules and Globemaster are capable of delivering their cargo in flight. Air Force’s fleet of five KC-30A Multi-Role Tanker Transport are converted Airbus A330 airliners, which means the aircraft’s lower cargo deck—normally utilised for carrying luggage containers—has been ‘militarised’, and can take military pallets as well. The KC-30A can airlift 34 tonnes of cargo. The fleet of rotary-wing transports in Army provide increased mobility for Defence units, being able to pick up and deliver cargo independent of a runway or drop zone. Army’s seven CH-47 Chinooks can lift up to 12 tonnes of cargo, either externally or internally, whilst the fleet of 35 S70A Black Hawk can carry four tonnes of cargo externally. Army and Navy are in the processes of introducing a fleet of 46 MRH90 Taipan helicopters to service, which can take four tonnes of cargo under external lift, or carry small items of cargo. Current acquisitions for Defence which will involve AMTDU include the C-27J Spartan Battlefield Airlifter; the CH-47F Chinook; and the MH-60R Sea Hawk. 5 [Above] A C-130J Hercules lifting off from an airfield in Afghanistan. Different variants of the C-130 have been in service since December 1958, and all have had largely similar cargo dimensions. The C-130J, introduced from 1999, features an extended fuselage which can accommodate a greater volume of cargo. [Above] The KC-30A Multi-Role Tanker Transport (left) and the C-17A Globemaster have recently brought about a massive increase in cargo capacity, as well as the distance and speed with which that cargo can be transported. [Above] Army Aviation’s rotary-wing airlift is centred on the CH-47D Chinook (left) and the S70A Black Hawk. In the near future, the CH-47D will be replaced by the newer CH-47F variant, while the S70A will be replaced by the MRH90 helicopter. Why Air Movements Matters All transport aircraft must be able to deliver cargo and personnel to a destination safely and in working order. The Australian Defence Force has strict standards on the practice of carrying cargo onboard its aircraft, as poor techniques can threaten the safety of cargo, the aircraft, or even the occupants of an aircraft. Loads carried by Defence aircraft must be able to endure stresses and manoeuvres which would be considered ‘routine’ on dayto-day operations, as well as preventing them from becoming a hazard in the event of an aircraft incident. Cargo loads must be expected to withstand increased forces of gravity when the aircraft manoeuvres. Inside an aircraft they must withstand restraint loads of up to 3Gs, whilst during airdrop operations, a load must be able to withstand 4Gs during the extraction from an aircraft; and between 12-20Gs on impact with the ground (with descent parachutes). Loads being carried externally beneath a helicopter must be able to withstand 2Gs, but also not affect the aerodynamic stability of the aircraft. [Above] The brown box represents a payload inside the Hercules, and its centre-of-gravity (yellow arrow) is balanced with the Hercules’ own centre-of-gravity (red arrow). [Above] In this example, the payload is positioned too far forward inside the Hercules, meaning its centre-of-gravity is out of sync with the Hercules’ own. If the difference is too great, the aircraft would not be airworthy. Developing loads for carriage by aircraft requires AMTDU to investigate the load and conduct trial work to determine whether it is suitable for carriage by a certain aircraft, and that other Defence members can be instructed on this practice. When assessing whether a load is suitable for carriage on board an aircraft, AMTDU personnel will do the following: Assess the load, including weight, compo- nents, structure, suitable attachments for restraints, centre-of-gravity, dangerous goods, and ease of transportation. 6 [Above] When an aircraft accelerates, decelerates, or undergoes any kind of manoeuvring, the load experiences additional forces (demonstrated by the yellow arrows). If the load is not properly restrained within the cargo bay, it will break free and damage (or even destroy) the aircraft. Assess the aircraft carrying the load, in- cluding its performance, cargo space, requirement to carry the load, and access. Examine similar practices within AMTDU’s own experiences, or within foreign militaries. With these details in hand, AMTDU Engineers, Loadmasters and Air Dispatchers will develop a load plan for a RAAF transport aircraft which provides the following: Correct preparation of the load (for exam- ple: removing blades and extremities from a helicopter, or ensuring that harmful materials within the load are either removed or stored properly). Correct loading technique. Correct positioning of the load within the aircraft’s cargo bay. A ‘Restraint Plan’, showing where tiedown chains and other restraints should be attached between the cargo floor and the load. If the load is required to be ‘airdropped’ from an aircraft, further investigation is made into whether it can safely be extracted from the aircraft in flight, deploy descent parachutes, and land on the ground intact and in working order. [Above] During airdrop missions, the payload must be able to safely and quickly exit the aircraft. [Above] Airdrop missions also require complicated analysis of the payload to ensure that it can survive the stresses of landing on the ground under a parachute descent. Similar practices are required when developing loads for internal carriage by an Army or Navy helicopter. If the load is being carried externally by helicopter, the following must be considered: Aero-dynamic interaction between the load on the helicopter, and the load’s stability underneath the rotorwash. The strength of the load’s lift points and structure, as well as the affect of the restraints (or ‘strops’) on the load as it is carried. The load’s impact limits, when it is ‘set down’ by a helicopter. 7 [Above] External carriage of cargo (demonstrated here by an MRH90 carrying an artillery piece) requires further examination on the cargo’s best attachment points; how it will be affected by the helicopter’s rotorwash; and its behaviour in airstream, once the helicopter begins moving forward. A History of Air Movements In 1942, the outbreak of war in the Pacific saw Air Force introduce a fleet of ex-civilian airliners to serve as a transport fleet, allowing Australia’s military forces better mobility across the South West Pacific theatre. These airliners were later replaced by the C-47 Dakota, a twin-engine transport capable of airlifting up to two tonnes of cargo. The Dakotas endured through post-war RAAF service, and even by the late 1940s, had begun to show their shortfalls. New transport aircraft offered larger cargo holds and easier loaded/unloading techniques. Never the less, the Dakota remained the mainstay of RAAF airlift well into the 1950s. In the post-war Air Force, air transport training had become a subset of No. 38 Squadron at Headquarters RAAF Canberra. The training was conducted by the Air Portability and Air Movements Training Flight. In October 1958, No. 38 Squadron was relocated to RAAF Base Richmond, and the Air Movements Training Flight (AMTF) was formed to train C47 Dakota aircrew and air movements personnel. In December 1958, Air Force introduced the C-130A Hercules to service. This presented a quantum leap in cargo-carrying capability for the RAAF, being able to carry nine times the cargo of a Dakota, as well as carrying vehicles and bulky, outsized items. The introduction of the Hercules led the AMTF to become responsible for training and creating air movements procedures for this aircraft. In the early 1960s, Air Force massively expanded its transport fleet, capitalising on the development of fixed and rotary-wing aircraft development out of North America. This matched the increase commitment of Australian forces to Vietnam, and soon, Air Force 8 [Above] The RAAF began flying the C-47 Dakota in 1942, and for the next 16 years, it remained a mainstay of airlift, serving in the Second World War, Korean War, Malayan Emergency, and Berlin Airlift. [Above] In 1958, the RAAF transitioned from Dakota to more capable aircraft like the Hercules (pictured above). This heralded a massive increase in the size of cargo that could be carried by RAAF aircraft, as well as the means by which it could be delivered. [Above] The introduction of the UH-1 Iroquois in RAAF service from 1962 provided even more mobility for Defence units, with the added bonus that the Iroquois itself could be transported to a far-flung destination by Hercules. introduced the DHC-4 Caribou, UH-1 Iroquois helicopter, and the C-130E Hercules to service. This much larger transport fleet led Air Force to make the AMTF an independent body, leading to Air Movements Training and Development Unit (AMTDU) being established in October 1965. This was a unique unit comprised of both RAAF and Army personnel. On 1 July 1997, the Aerial Delivery Centre of Expertise (ADCOE) under No. 503 Wing was placed under command of AMTDU, and underwent a name change to Airworthiness Flight (AWFLT). This meant that all aspects of airworthiness including engineering acceptance and approval were now under one command. In December 1997, AMTDU and AMTDU (Army Component) amalgamated and became a joint unit. Today, AMTDU sits directly under the command of Headquarters Air Mobility Group. Subsequent purchases of new transport aircraft (including the C-17A Globemaster, CH47 Chinook) have led AMTDU to become increasingly busy as it clears loads for carriage by these aircraft. New equipment purchases such as the M1A1 Abrams Tank, Bushmaster PMV, ASLAV, Mercedes G-Wagon and John Deere 450L Bulldozer have likewise kept the unit busy. AMTDU also conducts a significant amount of short-notice and operationally urgent work to clear loads. This has included returning damaged Bushmaster PMVs from the Middle East Area of Operations and transporting special loads in theatre; supporting the deployment of a desalination plant to Christchurch and support equipment to Japan following natural disasters in those countries; and clearing Japanese Self-Defense Force vehicles for carriage by RAAF C-17As during disaster relief operations. 9 [Above] The DHC-4 Caribou served with the Air Force from 1964 to 2009, and was renowned for its ability to deliver cargo by airdrop or by landing on tiny airstrips. The Caribou could also use a Low Altitude Parachute Extraction System (LAPES, seen here) to deliver cargo. [Above] In 2006, Air Force introduced the C-17A Globemaster III to service, ending Defence’s sole reliance on foreign Air Forces and civilian charters for strategic-level airlift. The C-17A is also capable of tactical roles such as airdrop, illustrated here. [Above] From 2015, the RAAF will begin operating the C-27J Spartan, which fulfils an airlift gap between Army’s CH-47 Chinook and Air Force’s C130J Hercules. [Above Left] A SAAB Counter-Rocket Artillery and Mortar Radar is unloaded from a C-17A in Afghanistan. The carriage of the radar, which was a firsttime load for Defence, required an AMTDU team to travel to Sweden to assist in the pick-up and delivery of this load. [Above Right] An MRH90 undergoing external airlift trials with an artillery piece in Townsville. The MRH90 will form the backbone of Army’s rotarywing airlift when it replaces the older S70A Black Hawk. [Right] An Army G-Wagon is transported beneath an Army Aviation CH47D Chinook. Defence is purchasing a fleet of Mercedes G-Wagon to fulfill a number of transport, communications and ambulance requirements. [Below Right] A string of Container Delivery Systems (CDS) exits the back of a C-130J during an airdrop trial. The C-130J can accommodate up to 26CDS in its cargo bay, and each CDS can be used to carry water, supplies and rations, or ammunition. [Below Left] In March 2011, AMTDU deployed to Japan with the C-17A to assist in loading Japanese Ground Self Defense Force vehicles, in response to the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami. [Above] A John Deere 450L Bulldozer is extracted from a C-130H Hercules during an airdrop trial in October 2012. The bulldozer is able to clear land (such as for makeshift airstrips and roads) once on the ground. [Right] An LR5 Submersible Rescue Vehicle is unloaded from a C-17A. The LR5 and its support equipment can be transported anywhere in the globe by air, and is then taken by ship to be used in the rescue of stranded submariners. [Below Left] In May 2008, AMTDU assisted in the transport of two Super Puma helicopters from South Africa to Thailand, whereby they were used for United Nations efforts in Burma following Cyclone Nargis. [Below Right] The CH-47D Chinook was one of the first loads AMTDU cleared for the C-17A, reflecting both the C-17A’s ability to carry outsized cargo, and the essential nature of the Chinook to operations abroad. 12