BASEBALL AS A MICROCOSM OF AMERICAN WEST SOCIETY

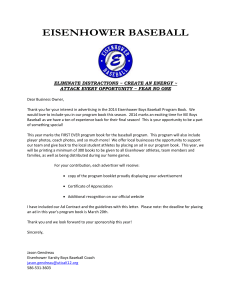

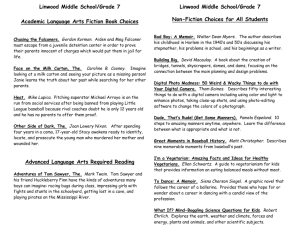

advertisement