The Care Act and whole family approaches

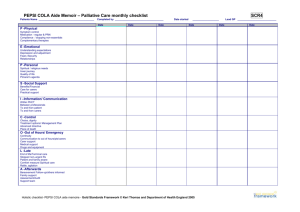

advertisement