BPOC

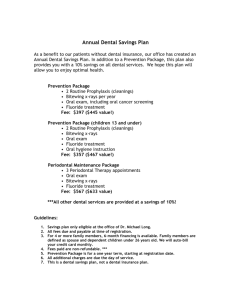

advertisement