Understanding Second Language Teacher Practice Using

advertisement

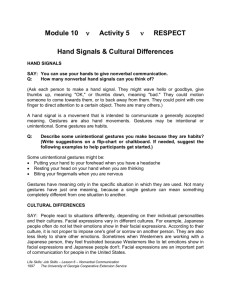

Understanding Second Language Teacher Practice Using Microanalysis and Self-Reflection: A Collaborative Case Study ANNE LAZARATON ESL/ILES 214 Nolte Center University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455 Email: lazaratn@umn.edu NORIKO ISHIHARA 214 Nolte Center University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455 Email: ishi0029@umn.edu Research on second/foreign language teacher impressions, reflections, and beliefs continues to illuminate various facets of language teacher knowledge and practice, but it has only recently begun to question the relationship between these teacher characteristics and actual classroom discourse. This collaborative case study undertaken by a discourse analyst and an English as a second language teacher concurrently analyzed data from one segment of transcribed grammar classroom interaction and the teacher’s focused self-reflections in order to examine the insights both participants independently brought to bear on the understanding of the nonverbal behavior in the segment under scrutiny. Through these analyses and the collaborative dialogue that ensued, both the discourse analyst and the teacher came to reevaluate their research methodologies and to conclude that the microanalysis of classroom discourse and the teacher self-reflections complemented each other by providing insights that neither method generated in isolation. IN RECENT YEARS, THE FIELD OF APPLIED linguistics has witnessed the emergence and expansion of second/foreign language (L2) teacher education as a vibrant subfield, one that is, in some ways, almost independent from other subfields such as language assessment and language acquisition, due to its unique theme of educating and informing pre- and in-service language teachers. The vast majority of empirical work on L2 teacher practice has focused on teacher beliefs, impressions, and reflections about decisionmaking process, practical knowledge, and the like—data sources that are the standard in language teacher education research (e.g., Freeman & Johnson, 1998b; Johnson, 1999). The methods of self-reflection and narrative inquiry in the study of language teaching have been shown to be use- The Modern Language Journal, 89, iv, (2005) 0026-7902/05/529–542 $1.50/0 C 2005 The Modern Language Journal ful and viable tools for teacher professional development (Cheng, 2003; Johnson & Golombek, 2002). However, such research, focusing on language teacher knowledge and beliefs, has, until recently, neglected to consider an additional, potentially crucial factor—the actual discourse produced in these teachers’ classes. Close examination of classroom discourse recorded precisely as it happens not only allows detailed analyses of classroom practices, but can also validate or provide counterevidence to the self-reflection provided by the teacher. It would be a mistake in this kind of close examination of classroom discourse to consider only the insights of the discourse analyst and not the insights of the participants in that discourse— in particular the classroom teacher. The teacher’s interpretation of the discourse might also support or disconfirm the researcher’s analysis of this talk. In other words, it is an empirical question whether or not, or to what extent, there is a match between (a) what teachers say they know and believe, and 530 what they actually do, and (b) the researcher’s and the teacher’s understanding of the classroom discourse, as revealed by fine-grained analyses of it. This article reports on a collaborative case study by a discourse analyst and a practicing English as a second language (ESL) teacher and represents an initial attempt to answer three related questions on this topic: 1. What insights can a discourse analyst bring to bear on the understanding of a teacher’s nonverbal behavior as displayed in the classroom discourse, and what additional insights can he or she gain through collaborative dialogue with the teacher that were not otherwise obvious by working independently? 2. What insights can an ESL classroom teacher bring to bear on the understanding of his or her own nonverbal behavior as displayed in the classroom discourse, and what additional insights can he or she gain through collaborative dialogue with a discourse analyst that were not otherwise obvious by working independently? 3. How can the analyst and the ESL teacher come to reevaluate their respective methodologies as a result of collaborative dialogue? BACKGROUND In recent years, applied linguists have focused their attention on L2 teacher education and practice; classroom discourse has been a locus of interest for quite some time. On the one hand, there is a growing body of research published on the topic of language teacher education in the form of books (e.g., Freeman & Richards, 1996; Johnson, 2000; Richards & Nunan, 1990) and research articles (e.g., the special issue on language teacher education in the 1998 TESOL Quarterly [Freeman & Johnson, 1998a], and many more elsewhere). Studies in language teacher education are now regularly presented at conferences such as the annual convention of Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL; under the rubric of the teacher education interest section). The biannual conference specifically on this topic, the International Conference on Language Teacher Education (ICLTE), is now well-established with increasing participation by teacher educators from around the globe. Themes that are prevalent in this scholarship include: the conceptualization of the teachers’ knowledge base and its relationship to student learning (e.g., Freeman & Johnson, 1998b; Johnson & Freeman, 2001; Johnston & Goettsch, 2000); teacher practice or beliefs, or The Modern Language Journal 89 (2005) both (e.g., Breen, Hird, Milton, Oliver, & Thwaite, 2001; Burns, 1992; Crookes, 1997; Johnson, 1992); the role of theory in language teacher education (e.g., Johnson, 1996; Schlessman, 1997); curricula and instructional techniques in language teacher education programs (e.g., Freeman & Cornwell, 1993; Ishihara, 2003; Kamhi-Stein, 2000; Stoynoff, 1999); and reflective teaching and action research (e.g., Johnson & Golombek, 2002; Johnston, 2001; Richards & Lockhart, 1996; Stanley, 1998, 1999). From a teacher’s standpoint, systematic selfreflection (i.e., critical self-inquiry about one’s own teaching practice) requires the teacher to make a serious and sustained commitment to scrutinizing teaching principles and practices; this self-critique process is known to be rigorous and sometimes painstaking (Johnston, 2001; Stanley, 1998). Action research, which most often relies on teachers’ self-reflection on their own teaching beliefs and practice, if conducted systematically and extensively, promotes the construction of teachers’ knowledge of their own practice, including experiential knowledge, disciplinary knowledge, and sociocultural knowledge of the teaching context. Although first-person narratives have generally been marginalized as valid data in the social and human sciences (Pavlenko & Lantolf, 2000), in the body of research on language teaching, self-reports have been extensively and reliably employed as legitimate data sources (e.g., Freeman & Richards, 1996; Johnson, 2000; Johnson & Golombek, 2002; Woods, 1996). Furthermore, the process of action research through reflective practice or self-inquiry enables the construction of teacher-generated knowledge (Cheng, 2003), thus empowering teachers as the creators and not just the holders of such knowledge (Beattie, 1995; Johnson, 1996). On the other hand, applied linguistics researchers have long been preoccupied by the nature of talk produced in L2 classrooms, especially classes where students are learning ESL. For the most part, this research has examined classroom discourse in order to determine its impact on language acquisition by the learner, but has not explored the relationship between talk in classrooms and teacher knowledge or beliefs. Chaudron (1988), for example, summarized literally hundreds of studies (most of which were both experimental and quantitative in nature) that analyzed: the amount and type of teacher talk; learner verbal behavior with respect to age, culture, and language task; teacher–student interaction in the L2 classroom as shown through questioning behavior and corrective feedback; and the influence of these factors on learning outcomes. More Anne Lazaraton and Noriko Ishihara recently, Johnson’s (1995) book analyzed the ways in which teacher communication patterns influence and in some ways restrict student participation opportunities, and by extension, their acquisition of a L2. Several later studies have employed interpretive techniques in analyzing actual recorded and transcribed talk to understand, for example, the means by which ESL teachers answered student requests for definitions of unknown vocabulary (Markee, 1995), the ways in which the discourse patterns present in an adult ESL conversation class were influenced by particular instructional goals of the teacher (Ulichny, 1996), and the ways in which teacher practices in the classroom led to “community stratification,” where “deficient” students were barred from beneficial classroom activities (Toohey, 1998). Yet, a notable limitation of almost all of this L2 classroom-based research, in its nearly exclusive focus on the learner, is its failure to consider the insights and perspectives of the teachers in question. It is heartening to see that a few studies (including several unpublished doctoral dissertations) have begun to question the assumed (or overlooked) link between beliefs about teaching and how teaching is actually practiced. Martinez (2000) investigated the relationship between the educational beliefs and the classroom literacy practices of a first-grade bilingual teacher. Her conceptions of her students, her students’ learning, as well as her perceptions about literacy instruction and the extra-classroom demands on her, were shown to guide her literacy practices. Tucker (2001) also compared teacher beliefs about language learning theories and teaching methods with classroom practice in data collected from middle school English classrooms in China. Tucker found that there was no relationship between stated beliefs and actual practice. Mastrini-McAteer (1997) looked at the beliefs and practices of 18 third-grade reading teachers and concluded that just over one quarter of the teachers taught in congruence with their stated beliefs about reading instruction; prior experience seemed to influence beliefs about reading instruction the most, while actual classroom practices were most affected by the materials used in the classes. In addition, classes in which the teachers taught reading according to their beliefs showed significantly greater gains in student achievement. Classroom literacy practices were also analyzed by Wharton-McDonald, Pressley, and Hampston (1998), who conducted interviews with and observations of three groups 531 (n = 9) of first grade teachers. Data from the observations indicated that the three outstanding teachers’ classes were rich in authentic reading and writing practice; these activities were balanced with explicit instruction in literacy skills. Comments from the teachers were taken as evidence of teacher beliefs about the importance of scaffolding, of having high expectations of students, and of having an awareness of purpose about class activities. Finally, rather than looking broadly at classroom practice via observations, Oskoz and LiskinGasparro (2001) published a case study on the beliefs about and the discourse of corrective feedback in a university-level Spanish class. Three hours of classroom instruction were audiotaped and coded for various features of feedback reported in previous literature. The teacher, a native speaker of Spanish, was also interviewed to elicit information about her beliefs on this classroom practice. She professed a belief that students were inhibited by frequent correction, but the data indicated that she provided extensive corrective feedback, not just in form-focused activities, but in activities with a communicative focus, where she claimed to use recasts most frequently. Still, what is missing in this small body of work is an explicit connection between classroom discourse, on the one hand, and the teacher’s voice, on the other. It is the thesis of the present article that both language teacher educators and discourse analysts need to consider both forms of information—that is, the insights gleaned from teacher-directed, self-reflective action research and the results generated from researcherdirected microanalyses of classroom discourse. This collaborative process would allow us to determine, first, if there is a congruence between analyses of discourse and analyses of beliefs and impressions, and if there is not, to suggest a line of research that would stimulate further teacher reflection and reinforce the discourse analysts’ empirical claims. That is, such research has the potential to inform us about, on the one hand, what sorts of unique information each type of analysis provides, and on the other, how each analysis may complement the other. This article represents an initial attempt to consider the insights provided by these two approaches to understanding L2 teacher practice by reporting the results of a collaborative case study project undertaken by an applied linguistics researcher using discourse analysis and an ESL classroom teacher using reflective practice. After a synopsis of our data collection procedures, we present the results of our collaborative research. 532 METHOD The data for this study were collected over a 20month period in 2001–2002. Table 1 represents a schematic of this process. Participants Initially, the researcher (R) was awarded a grant to analyze the discourse that is present in Intensive English Program (IEP) ESL classrooms at a large, Midwestern university. In February 2001, she approached two teachers (T and another teacher, who is not discussed in this article) who agreed to take part in the study, which involved videotaping three 50-minute classes each during a 15-week semester. T’s classes were videotaped by university language center personnel during February, March, and April of 2001 in a university classroom equipped with two mounted corner cameras, several external microphones suspended from the ceiling, and one Sound Grabber table microphone at the front of the room. The camera setup allowed the researcher to view T’s whole body movements and her gaze, but did not capture in any systematic way the behavior or the talk of the students. T, a female master’s degree candidate in ESL in her late 20s from Japan, had 5 years of EFL teaching experience in a private language school in Japan and 1 year of U.S. ESL experience as a teaching assistant in the IEP at the time of the taping. Three of her Level 4 (of 7) university intensive English grammar classes were taped. The teaching points for those days were: (a) relative clauses and gerunds, (b) past progressive verb tense, and (c) mass/count nouns and quantifiers. The Modern Language Journal 89 (2005) A total of 23 students were participants in one or more of the three videotaped classes. There was a nearly even mix of males and females, from their late teens to their early 30s. Nearly half of the students were from Korea and about one quarter were from Saudi Arabia; 10 other countries were represented in this group of learners. Procedures R carefully viewed each of T’s three tapes after recording in order to come up with some initial questions that might be pursued in future discourse analyses. One aspect of T’s behavior that immediately struck R as notable was the frequency and the variety of nonverbal behavior— including gestures, gaze, and body positioning— that T employed in her intermediate-level grammar classroom, especially behavior that accompanied a number of unplanned explanations of vocabulary that arose during her three focuson-form lessons. R decided that gesture use would be one area that she would look into further. T and R discussed the possibility of doing some collaborative research on T’s teaching, but this research was not undertaken until the fall of 2002. Coincidentally, at about the same time, T, being in the second year of her master’s program in teaching ESL, was engaged in some serious selfreflection about her classroom teaching. Attempting to evaluate her own teaching on the one hand (Where do I stand as an ESL teacher after several years of teaching EFL and ESL, and what are the issues of my teaching?), she was challenged to grapple with more fundamental questions (What prevents me from teaching as I believe? What are my teaching principles?) in the fast-paced life of TABLE 1 Data Collection Procedures Researcher Teacher Videotaping of teaching: February–April, 2001 Initial inquiry: February–March, 2001 Initial impressions about teaching: February–April, 2001 Transcription of verbal channel by a research assistant: July, 2001 R1 Addition of nonverbal behavior to transcript and T1–T2 Initial reactions and reflections: July, 2001; microanalysis: July, 2002 July, 2002 R2–R4 Written reactions to T3–T6 Written reactions and teacher’s writings: October 22, reflections: October 5, Meetings to watch videotapes and 2002–November 18, 2002 −−−−→ collaborate on ideas: August 21, ←−−−− 2002–November 18, 2002 ←−−−− −−−−→ 2002–October 24, 2002 Note. R = Researcher; T = Teacher; R1–R4 = Researcher’s analytic notes, comments; T1–T6 = Teacher’s data source for action research. 533 Anne Lazaraton and Noriko Ishihara a teacher and graduate student. On the other hand, she felt that, due to the nurturing nature of the master’s degree program in which she was enrolled, she had not received much constructive feedback about her teaching, yet she thought some critique would be crucial to improve her teaching. Therefore, she accepted R’s request to participate in the study as an opportunity for both a diagnosis of and a systematic reflection on her teaching. In order to investigate her teaching behavior and to make more specific inquiries about her teaching, T adopted the methods of selfreflection. Of course, it was evident that her teaching concerns could not be dissociated from her status as a nonnative English-speaking teacher, and her reflection, as it is presented below, occasionally draws on this perspective. Nevertheless, the focus of this article rests on one aspect of her teaching, namely her use of nonverbal behavior, and we view our research more broadly, as an issue relevant to both native- and nonnative-speaking language teachers seeking professional development. The action research (or more specifically, exploratory practice)1 on her part prompted further questions and self-examination, which will be discussed in detail. During the summer of 2001, a graduate research assistant, under the supervision of R, transcribed the audio portion of the three videotapes using conversation analysis (CA) conventions (Atkinson & Heritage, 1984; see Appendix). This process resulted in about 75 pages of transcription for T’s three 50-minute classes. Then, over the summer of 2002, R undertook a detailed analysis of T’s nonverbal behavior, using the broad categories summarized by McNeill (1992).2 This analysis required additional transcription of the visual aspects of her teaching, using a “second-line transcript” (see Lazaraton, 2002). In July, 2002, R completed a manuscript on T’s nonverbal behavior (see Lazaraton, 2004, for a comprehensive literature review on this topic); some of the findings from this analysis are discussed below. Concurrently but independently, T was asked to begin an examination of her nonverbal behavior on the teaching videos. The initial reflections from and reactions to the videotapes by T are included in the results section. Beginning in August of 2002 and continuing to October of the same year, T and R met to view the videotapes together and discuss their content. Each of these seven meetings was audiotaped. T produced a rough transcription following each session so that we would have a written record of what we discussed, from which we would be able extract relevant analytic comments. Following our third meeting, T began a series of four written reflections and reactions, to which R responded in turn. This process resulted in a written, collaborative dialogue between T and R, from which we were able to detect several themes, including corrective feedback practices, classroom management issues, cultural knowledge displays, and nonverbal behavior. Before turning to a discussion of this last aspect of T’s classroom practice—her nonverbal behavior—we would note the potential richness of our data and the multiple layers of information they contain. It is no easy task to interweave these layers of information. The results we now present are just one (and certainly not the only or the best) attempt to make sense of our experiences with the data. RESULTS Three central findings that emerged from our collaboration are discussed below: (a) R’s discourse analysis of T’s nonverbal behavior and her subsequent awareness of its limitations; (b) T’s interpretation of her teaching practice through action research, that is, her journey of selfreflection, and the insights gained through collaborative dialogue with R; and (c) T’s and R’s methodological reevaluations, derived from and stimulated during the collaboration, for understanding L2 teacher classroom discourse and for understanding teaching and articulating beliefs. R’s Discourse Analysis of T’s Nonverbal Behavior Using information gleaned from the few empirical applied linguistics studies on nonverbal behavior (e.g., Allen, 2000; Gullberg, 1998; McCafferty, 1998, 2002) and employing the discourse analytic technique of microanalysis (as in Lazaraton, 2002; Markee, 2000), R carefully scrutinized the nonverbal behavior that occurred during one sort of classroom talk in the data: the unplanned vocabulary explanations in T’s grammar lessons. Sequences in which vocabulary was explained seemed a logical place to start examining nonverbal behavior, given that such behavior, as a communication strategy, is thought to serve one or more functions: as a replacement of, a support for, or an accompaniment to lexical items or referents in discourse (e.g., Dörnyei & Scott, 1997). One sort of information that is commonly conveyed in the ESL classroom is the meaning of vocabulary words, which as we know, is perhaps the prototypical language use situation requiring the deployment of nonverbal behavior. For example, words like mislay, weave, majority of, and argue 534 were all explained verbally and with accompanying gestures, body movement, and gaze by T. The most complex and most interesting of the fragments analyzed concerned T’s explanation of the word hypothesis. This explanation took place in the context of practice with count, noncount nouns, and the plural forms of count nouns. T had just explained the irregular plural form for hypothesis and theory, when a student (S1) asked her to define hypothesis (see Excerpt 1). In line 2 of Excerpt 1, T confirms the word being asked about by echoing hypothesis? while walking towards the class from the board and assuming a thoughtful pose. She begins her explanation with “if you’re writing a (.) thesis” (a term which itself may be unfamiliar to these young, unmatriculated ESL students). Then she says “and you see one thing” and at one thing , her hands, with palms vertical and out flat, move up and down three times. The verbal emphasis on one thing is reinforced by the “beat” gestures that go with it. Next, she says “and you’re thinking of why:,” with why in clause final position and emphasized by its lengthened vowel. Concurrent with the onset of talk is her metaphoric gesture, pointing her right index finger to her head (again, suggesting thinking). The kay serves as a confirmation check, followed by “an you’re guessing,” the last word cooccurring with her right index finger, still at her temple, making a circling motion (a metaphoric gesture suggesting wheels of thought). After a .2 second pause in line 8, she continues, using the target vocabulary word, “hypothesis one this is beca:use of this.” An enumerative structure is projected by the one and a cause and effect rhetorical structure is suggested by the beca:use. The hand gestures that come with this talk are as follows: at “hypothesis one,” her hands, in front of her at her chest, are placed in a clapping position, which she moves from right to left. This may also signal metaphorically a cause and its effects. The verbal production of “hypothesis two” in line 10 occurs with the same hand position as for “hypothesis one”: both hands in front of her in a clapping position at her chest level. This phrase is followed by “so you’re (.2) uh lining up (.2) reasons” in lines 10 and 12. At you’re, T’s right hand moves vertically from chest to waist in three chop movements, a metaphorical gesture suggesting the physical structure of a list. At lining up, there are two more of the same vertical chop gestures, again suggesting a vertical list (although lining up is perhaps more a horizontal notion). Finally, at reasons, there are two more of the same gesture, followed by a self-correction, possible reasons, which occurs with five hand chops, The Modern Language Journal 89 (2005) then the restatement of the lexical item in line 14: “they’re called (.) hypotheses.” In line 15, S1 shows her (mis)understanding of this explanation by asking, “just like um: like an opinion or?” An unidentified student repeats reason in line 16, which is overlapped by T herself repeating “reasons yeah” in line 17. She then undertakes a second attempt to explain hypothesis at “like you say:,” she resumes the thoughtful pose again, which is followed by “students in this class are nowt happy” (apparently an example of an observation she might make), at which time she again points to her head with her right index finger. She then adds “and I am thinking why?” At why? she looks out the window of the classroom they are in. She adds “maybe it’s because it’s so: snowing so much.” At maybe, she points out the window, where the students can see a snowstorm raging (a good possible reason to be unhappy on April 16!). And at so much, she puts her right thumb up in a “thumbs up” position to indicate number 1. She then adds another possible reason in line 25: “maybe its um maybe they don’t like American food?” Here maybe is accompanied by a head shake “no,” and at food, she adds her raised right index finger to her raised right thumb to signal number 2. After a comprehension check, kay in line 27, she says “I’m guessing reasons” (contrasting with lining up reasons in her first attempt), which occurs with two more vertical chops of the same metaphoric gesture for a list structure. She finishes up her explanation by saying “they are hypotheses” in line 29, which again is accompanied by three vertical chops. During the 2.5 second pause in line 31 and through line 34, she nods. She also does two verbal comprehension checks, umkay and alright, before resuming her instruction on these nouns. Here is R’s conclusion about this fragment: In this example, T demonstrates both the highly complex and interrelated nature of gestures and speech and her competence at using these forms of communication; we also see how these gestures add critical information to the verbal explanation being given. A metaphorical gesture which implies “thinking” by pointing to the head, the concept of “guessing” that is conveyed through the metaphorical gesture “wheels of thought,” a cause and effect structure which is implied by the right to left “beat” gestures, and a physical list of reasons which is depicted by creating an imaginary vertical list with hand chops: all of these gestures support and add redundancy to the verbal message she relates. (R1, 7/11/02) Whereas this conclusion is still valid for R, she also understood that her transcription of the Anne Lazaraton and Noriko Ishihara EXCERPT 1 Hypothesis 1 S1: um whats mean (.) hy?- 2 3 TE: hypothesis?,.hhh [um if you’re writing a (.) thesis [walk toward class, assumes “thoughtful pose” 4 5 (.) and you see [one thing (.) [and you’re thinking of [palms flat [point rt. index and vertical finger to head move up and down 3 times 6 7 why: (.) kay? an you’re [guessing [rt. index finger in circle motion 8 9 (.2) [hypothesis [one [this is be[ca:use of [this [hands in clapping [hands in clapping position at chest position at chest, move R→L in two move R→L in three beats beats 10 11 (.2) [hypothesis [two so [you’re (.2) uh [hands in clapping [RH flat and horizontal position at chest move down in three chop move R →L in two movements beats 12 13 [lining up (.2) [reasons (.) [possible reasons −→ [RH flat and horizontal [same but move down in two chop five chops movements 14 they’re called (.) hypotheses 15 S1: just like um: like an opinion or? 16 S?: rea[son 17 18 TE: [reasons yeah. (.) [like you say: (.2) [thoughtful pose 19 [students in this class are nowt happy 20 [point rt. index finger to head 21 22 (.) and I am thinking [why? (.2) [look out window 23 24 [maybe it’s because it’s so: snowing [so much, [point out window [thumb shows #1 25 26 (.5) maybe [its um maybe they don’t like [shake head “no” 27 28 american [food?, kay? [index finger shows #2 29 30 [I’m guessing reasons (.) [they are hypotheses. [RH flat and horizontal [same but move down in two chop three chops movements 31 32 [(2.5) [nodding thru line 33 33 TE: 34 35 36 umkay (2.0) TE: [alright? [looks to left then down 535 536 nonverbal behavior might have been too rough, and her data too meager. But it was only as a result of this collaborative study that she was made acutely aware of the inherent limitations of her microanalysis for understanding this segment of classroom discourse. This realization was one important outcome of the collaborative dialogues in which R and T engaged: T: While I gave two sets of explanations for what hypothesis meant, I used two ways to demonstrate the parallel relationship of hypotheses. When explaining that hypotheses are educated guesses, I used vertical gestures listing those guesses, intending to visualize the plural form of the word, the focal point of that grammar class. (T4, 10/19/02) R: Huh. I didn’t get the fact that the gestures were to indicate plural—in fact, I forgot that this segment was about singular versus plural and not primarily about the meaning of the word! (R2, 10/22/02) T: When the student asked me what hypothesis meant, my mindset was still “singular-plural” mode. Besides, I had explained that some nouns were count, some others noncount, and still others could be either depending on the situation . . . . Another point I made was that the distinction between count and noncount nouns was also sometimes counterintuitive and confusing . . . . Such conceptualization of nouns is very complex for this level of students (and perhaps anyone else) . . . . So while I explained the meaning of hypothesis, what I was trying to convey explicitly or implicitly, or at least what I had in the back of my mind was: (1) the meaning of the word, (2) the fact that even though it is an abstract noun, it can be counted (and always so, never noncount, unlike cheese, coffee or communication that can be either), (3) the irregular form of the plural of the word (as similar to oasis-oases, crisis-crises, basis-bases that we had discussed earlier in a few class periods before), and (4) the pronunciation of the plural form (with the lengthened vowel [i:] with a secondary stress as opposed to unstressed schwa in the singular form) as well as the pronunciation of singular (as it was difficult for this level, as you see S1 [one of the students in the video] could not pronounce the word while asking its meaning). (T5, 10/26/02) R: Okay, and all I got in my analysis was the construction of the vocabulary explanation itself—the words and gestures used to convey this information (1) I totally missed (2), its count noncount status, (3) its irregular form, since the sequence I analyzed did not consider the immediately prior talk on this, and (4) the pronunciation aspect. So I only saw what I was looking for—the overall goals of the sequence, and the class, were lost on me. (R4, 11/18/02) After this dialogue with T, R returned to the videotape to view the segment again, and retranscribed the word hypothesis as hypotheses in line 29, where The Modern Language Journal 89 (2005) the plural morpheme is said more emphatically. Although this fine-tuning of the data representation may not constitute an actual reanalysis of this segment, T’s input made for a more accurate transcription of the key word, and, by extension, a more informed view on what occurred, as well as why. In other words, the microanalysis worked well for understanding what happened in the segment, and how the explanation was accomplished. But it was limited to the sequence at hand; the larger pedagogical focus of the segment was missed. T’s Interpretations and Insights In T’s initial inquiries, very little attention was paid to nonverbal behavior; her written records (T1, 7/01; T2, 7/02) made no mention of that topic. The verbal aspects of teaching were so central for T that the nonverbal counterpart did not draw her attention. Moreover, in the collaborative dialogue with R, T initially expressed her skepticism a few times as to how meaningful her gestures were, and whether the gestures looked confusing. In her perception, her gestural repertoire was so limited that she suspected that the same gestures used for multiple purposes might have confused her students (Collaborative meetings 4, 9/16/02; and 6, 10/2/02). However, through reflection and discussion with R, T developed a new understanding about her nonverbal behavior in the classroom. Both studying R’s discourse analysis and collaboratively reviewing the teaching segment in question added objective evidence to T’s understanding of her own teaching. She came to believe that her nonverbal behavior was systematic and coordinated with the verbal explanation of the vocabulary: R: We can’t see it without a transcript, but the way that the gesture was coordinated with talk was just, it’s amazing how we do that as speakers. How the gestures get totally coordinated with the talk. (Collaborative meeting 6, 10/2/02) R: I was looking at the explanations integrated with the nonverbal behavior . . . . You got the words, and the gestures, totally integrated with each other to convey the meaning of the word. (Collaborative meeting 5, 9/25/02) T: What I thought were my idiosyncratic gestures indeed had labels, or had been used by others . . . (e.g., wheels of thought; the thoughtful pose, the cause and effect gesture). Since I try to use nonverbal behavior that is appropriate in American culture while teaching . . . I was happy to learn that my gestures made sense to a Western audience and were viewed as meaningful behavior that was consistent with my verbal Anne Lazaraton and Noriko Ishihara behavior . . . it was reassuring that these microanalyses verified my appropriate understanding and use of my second language nonverbal behavior. (T4, 10/19/02) This understanding gained through collaboration and reflection stimulated and finally enabled T to analyze and articulate her beliefs about nonverbal behavior in L2 teaching. First, upon hearing R’s comments “Gestures . . . have multiple meanings, just like words have multiple meanings” (Meeting 7, 10/24/02), T came to realize the multifunctional nature of gestures. Then, T’s renewed understanding of her use of gesture and her articulated belief about the use of nonverbal behavior in the L2 classroom was transformed into her new experiential knowledge, evidence of which we can see in her written reflection: T: It [non-verbal behavior] can certainly be an effective teaching aid that can bolster both teaching and student comprehension, provided that it is used in a pedagogically and culturally appropriate manner. To be effective, non-verbal behavior must be coordinated with the verbal counterpart in a non-obtrusive way, and used to send a consistent message. (T4, 10/19/02) This excerpt from T’s reflections clearly shows that the attention to nonverbal behavior brought by R provided T with an opportunity to reflect on one aspect of her teaching practice that she would never have examined if she had been working independently. The tools of reflection (in this case, the combination of [a] reviewing the videotaped teaching independently and collaboratively and [b] studying R’s discourse analysis and interpretation) led T to a new understanding of her teaching with regard to nonverbal behavior. With this tangible and objective evidence, T was able to articulate her belief about nonverbal behavior in the L2 classroom, which came to be new experiential knowledge of her own teaching. T’s and R’s Methodological Reevaluations For R, T’s final questions about the discourse analysis in which she engaged were quite revealing. T: How much did microanalysis inform you about my teaching? (T5, 10/28/02) R: It’s hard for me to answer this question about just this segment, because I have spent the last year using microanalysis to analyze lots of stuff in your teaching (and from the other teacher). What the microanalysis analysis has shown me is that for each of the factors I have looked at—cultural explanations, vocabulary explanations, gestural use, and corrective feedback— 537 there is a great deal of systematicity in your teaching. You have a repertoire of tools you use to accomplish these pedagogical activities. I have concluded in almost every case they SEEM no different to me than what a native speaker would do, but I have no data to back that up. (R4, 11/18/02) T: Could you have gotten the same insights just by watching the videotaped segment in question a number of times? R: No. I would have had some hunches that I could make, and I would be able to talk about your teaching in general ways, but only through the detailed and systematic analysis, watching the segments again and again, looking at the transcripts again and again. This is the only way I feel that I have “evidence” for the claims I want to make . . . . Watching the video is too fleeting—I have no way of holding in my mind what I see, and I have no way of comparing it with other segments that might or might not be alike. Microanalysis is like a pair of glasses that I put on that impose or suggest some sort of order (but not the only order, or even the best order) on the messy data that I analyze. It is interesting though that my initial impression, back when the data were collected, is that you use gestures very effectively and this is part of what makes you a good teacher. Microanalysis has not changed my opinion—it’s just given me a leg to stand on, so to speak. (R4, 11/18/02) T: How important is it to you to make any claim about second language teaching and teacher development? R: From a “pure CA” standpoint, not important at all. Real world pedagogical applications are just not central to CA. From an applied perspective, somewhat, although I think CA is limited in terms of what it can claim. It can explain how things are done, but not why. On the other hand, most (all?) language teacher research is concerned with why, so some how work is called for. However, I think that a triangulation of methods, like we have employed in this study, does show promise in ways that CA and self-reflection just can’t by themselves. If you think of CA as the how issue, and self-reflection as the why, it would make sense to do them together. (R4, 11/18/02) That is, R has a better grasp of the value, and the limits, of her discourse analysis of T’s teaching. The microanalysis shed light on how T brought her nonverbal behavior to bear on the vocabulary explanations she gave, but not on why. Only T could “round out” the analysis in such a way as to provide R with the necessary information to understand what the “Hypothesis” segment actually entailed, and how it was contextualized within the larger pedagogical frame of the activity, the class, and the course itself. In other words, R was forced to reexamine her own beliefs about participant voice in interpretive research, an always contentious issue in applied linguistics and 538 other related disciplines (e.g., Chapelle & Duff, 2003; Lazaraton, 2003; Markee, 2000; Moerman, 1988; Richards, 2003). Although R has, to date, eschewed appealing to or relying on ethnographic information from participants in her research, in line with prescriptions from conversation analysis, she has begun to question this purist stance. In this study, T’s input resulted in a retranscription of the key word being defined in the segment; this result only reinforces the point for R that T’s voice is perhaps the central one to which we should listen, because it is her insights, experiences, and reflections that underlie the study itself. For T, the process of action research and the construction of new knowledge can be traced in her self-reflective writing: T: In our collaborative dialogues, R asked me questions that I would never ask myself, and pushed me to think why I taught as I taught. Some of these questions stuck in my mind and stimulated further contemplation within myself. I questioned and rethought what I had told her, taking it to another level of thinking and understanding. How do I know what I know? What shapes my view of second language teaching/learning? In other words, such collaborative reflection and further reflection bridges my personal experience of being an EFL/ESL teacher/learner to my current teacher beliefs and professional identity in the United States. (T3, 10/05/02) The collaborative dialogues with R elicited T’s long-forgotten recollection of her past experience reading a book on her first language (L1) and L2 language gestures (Williams, 1998) and teaching gestures in her EFL classroom. The discussions also reminded T of the stated beliefs she had about teaching culture before entering the master’s degree program in ESL. Through extensive self-reflection, the empirical investigation of the classroom discourse, and the collaborative discussion with R, the action research employed in this study enabled her to make a connection between deeply buried subconscious beliefs, half-forgotten experience, and the currently constructed knowledge of her teaching, thus leading to her continued professional growth. Some teacher education literature argues that inquiry into teachers’ personal and professional language learning and teaching experiences allows teachers to link such experiences to their current teaching beliefs and practice (Fang, 1996; Johnson & Golombek, 2002). The methodological process of self-reflection and action research can also engender in-depth critical self-exploration by stepping back, reflecting, interpreting, and articulating one’s own practice of teaching to arrive at an awareness of one’s own knowledge about The Modern Language Journal 89 (2005) teaching (the construction and reconstruction of the teachers’ knowledge; Beattie, 1995; Johnson, 1996). A teacher’s experiential knowledge entails not only contextualized knowledge of the class (e.g., specific knowledge of the curriculum, materials, and learners, namely, the knowledge necessary for teaching and evaluating his or her classroom practice), but also knowledge of how his or her teaching beliefs came to be and how they relate to his or her own practice. This study also suggests that such knowledge can inform both the teacher and the discourse analyst in a broader context when the teacher functions as a research collaborator. LIMITATIONS Although we are pleased with the outcomes of our study, we would be remiss if we did not mention several potential drawbacks of this sort of collaborative work. For one, the labor-intensive nature of microanalysis of transcribed talk is well known by those who work in this area, and the time spent meeting each other, emailing back and forth to follow up and push ourselves forward, and systematically recording these events makes us somewhat cautious in recommending this approach to others. We should note that the results discussed here are only a small part of the data collected. In the future, we plan to follow a similar path in exploring our analyses of the corrective feedback that T used in her classes. Furthermore, we are acutely aware that our data, although quite enlightening, do not, in their current state, shed light on whether T’s newly gained knowledge about her teaching in fact led to enhanced teacher practice. Unfortunately, T has not formally taught ESL since the data were collected, so we have no information on this important question. In a similar vein, although earlier studies have reported learners’ enhanced listening comprehension by use of a certain type of gestures (“illustrators,” Harris, 2003), we have no evidence that the gestures T used led to enhanced student understanding (Johnson & Freeman, 2001) in this particular classroom. The majority of the students are no longer in the country, and even if they were, we know of no reliable or valid way of assessing the value of nonverbal behavior in student understanding or learning. In addition, because the discourse data came from videotapes of classroom interaction, the presence of the recording equipment undoubtedly influenced T’s classroom behavior. In fact, in one of our collaborative meetings, T noted that she felt very self-conscious during the 539 Anne Lazaraton and Noriko Ishihara tapings, perhaps not every moment but pretty much throughout the classes. Likewise, her students might have acted slightly differently because of the change in the seating arrangement from the regular classroom. These observations are not meant to negate our findings, but to suggest that we interpret them prudently, with respect to how T might or might not behave in a “normal” situation. No definitive claims about the nature of T’s nonverbal behavior can be made based on the one fragment analyzed in this article. Space limitations in publication venues almost always preclude mention of each relevant case in interpretive research. However, even an analysis and presentation of all such instances in the data are still subject to questions about how representative they are of T’s behavior in other, untaped lessons, with other students, teaching other language skills. Finally, of course, even though this collaborative process surely added to T’s experiential knowledge of her own practice, we cannot make claims about the generalizability of the experiential knowledge gains in this case study, or about how this experiential knowledge fits into the larger knowledge base of language teacher educators. And, we cannot be sure about the effectiveness of our research methodology for supplementing the interpretations of other discourse analysts working with other classroom teachers. IMPLICATIONS In terms of concrete suggestions for teacher training and development, we note these implications. First, teacher education programs may want to stress the importance of nonverbal behavior in L2 teaching. Although nonverbal communication reinforces or delivers meaning not communicated by verbal messages, it has been largely neglected in L2 pedagogy (Harris, 2003). For example, one prominent teacher education textbook used to teach Second Language Acquisition (Brown, 2000) discusses various modes of nonverbal communication as part of communicative competence, but its application to L2 pedagogy is addressed in only one of the discussion questions in the conclusion of the chapter. If nonverbal communication is to be counted as an effective teaching aid or strategy, then it needs to be given more attention in teacher development programs (Shaw, 2002). Native speakers use nonverbal communication at a subconscious level (Brown, 2000), yet language teachers must become aware of its largely culturally specific nature as well as the ways they actually use it and how it can be best exploited in L2 teaching. Nonnativespeaking language teachers may need to adjust their L1-based nonverbal behavior so as not to confuse learners when the L1-based nonverbal behavior is employed concurrently with the verbal target language. Given that nonverbal behavior is largely subconscious and if no training is provided on its effective application, it is likely that language teachers will use it without ever reflecting on or analyzing how such behavior is implicated in learning in the L2 classroom. Furthermore, in order to achieve the goal of effective language teaching, the importance of teaching by principles (Brown, 2001) has been argued. The numerous instructional decisions that teachers make in practice must be consistent with each other as well as with the teacher’s principles/beliefs; this consistency can be perhaps best attained by examining one’s teaching beliefs from a theoretical perspective and establishing a rationale for each instructional decision. Scrutinizing one’s practice and beliefs may prompt more informed or analyzed instructional decisions, which should lead to new practices that are more coherent. Conversely, a newly adopted practice can cause teachers to renew their teaching beliefs (Markee, 1997). The present study has shown that the collaboration between R and T brought T’s use of gestures to light and promoted a deeper understanding of her practice, which led to an articulated belief on her part. Although investigating potential or actual changes in T’s practice is beyond the scope of this study (again, because T has not formally taught ESL in recent years), such an analyzed belief about and awareness of her practice might facilitate behaviors that are more consistent with her principles in terms of the use of gestures. This improved consistency points to a potentially successful marriage of research and practice in teacher development. CONCLUSION To reiterate, we make the following claims based on the study reported here. First, the language teacher in this study was able to grasp more fully her own teaching practice, especially after one aspect of it—her nonverbal behavior—was brought to her attention by the discourse analyst, who found this behavior remarkable. Second, the discourse analysis and the teacher selfreflection together provided information that was unavailable to either the discourse analyst or the teacher using just one approach. Finally, not only did the two types of research generate different 540 information, but the particular results were then filtered through our collaboration, which ultimately shaped the perspectives that R and T have today on both discourse analysis methodology and L2 teacher practice, in general, and on T’s practice in particular. We hope that this article will engender further discussions among applied linguists about some fundamental issues in L2 classroom practice that have not received enough attention in our discipline. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank Elaine Tarone and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on previous drafts of this article. Any errors that remain are, of course, our own. NOTES 1 Although the term action research is used in this article for its broad scope (i.e., teacher-initiated investigation of teaching practice; see Richards & Lockhart, 1996), more specifically, T was engaged in exploratory practice. Allwright (2001) distinguished action research, in which a problem in the current practice calls for action for change, from exploratory practice, which derives from the teacher’s “puzzle” that promotes action for understanding. 2 The McNeill system for classifying hand movements that occur in face-to-face interaction include the following categories: Iconic gestures are closely related to the semantic content of speech, or as Schegloff (1984) put it, “shape links them to lexical components of the talk” (p. 275), which his work shows are generally pre-positioned with respect to the lexical element they invoke. Iconic gestures may be kinetographic, representing some bodily action like sweeping the floor, or pictographic, representing the actual form of an object, like outlining the shape of a box. Metaphoric gestures may be pictographic or kinetographic like iconics, but they represent an abstract idea rather than a concrete object or action. An example is circling one’s finger at one’s temple to signify the “wheels of thought.” Deictic gestures have a pointing function, either actual or metaphoric. For example, we may point to an object in the immediate environment, or we may point behind us to represent past time. Beats are gestures that have the same form regardless of the content to which they are linked. In a beat gesture, the hand moves with a rhythmical pulse that lines up with the stress peaks of speech. A typical beat gesture is a simple flick of the hand or fingers up and down, or back and forth; the movement is short and fast. Beats do not have referential meaning; rather, they seem to regulate the flow of speech. The Modern Language Journal 89 (2005) McNeill’s classification system also includes two hand movements that are not considered to be “speechassociated” gestures, and they are often excluded from systematic study. Emblems are culturally specific representations of visual or logical objects that have standardized meanings. Examples include the V sign for victory, the raised middle finger as an obscene gesture, and the like. Adaptors are unconscious movements performed by speakers, often in the form of grooming behaviors (playing with hair, rubbing one’s chin, etc.). REFERENCES Allen, L. Q. (2000). Nonverbal accommodations in foreign language teacher talk. Applied Language Learning, 11, 155–176. Allwright, D. (2001). Three major processes of teacher development and the appropriate design criteria for developing and using them. In B. Johnston & S. Irujo (Eds.), Research and practice in language teacher education: Voices from the field (CARLA Working Paper No. 19, pp. 115–134). Minneapolis, MN: Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition. Atkinson, J. M., & Heritage, J. (Eds.). (1984). Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Beattie, M. (1995). New prospects for teacher education: Narrative ways of knowing teaching and teacher learning. Educational Research, 37 (1), 53–70. Breen, M. P., Hird, B., Milton, M., Oliver, R., & Thwaite, A. (2001). Making sense of language teaching: Teachers’ principles and classroom practices. Applied Linguistics, 22, 470–501. Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching (4th ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman. Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (2nd ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman. Burns, A. (1992). Teacher beliefs and their influence on classroom practice. Prospect, 7 (3), 56–66. Chapelle, C., & Duff, P. A. (2003). Some guidelines for conducting quantitative and qualitative research in TESOL: Conversation analysis. TESOL Quarterly, 37, 169–172. Chaudron, C. (1988). Second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cheng, A. (2003). [Review of the book Teachers’ narrative inquiry as professional development]. TESOL Quarterly, 37, 181–182. Crookes, G. (1997). What influences what and how second and foreign language teachers teach? Modern Language Journal, 81, 67–79. Dörnyei, Z., & Scott, M. L. (1997). Communication strategies in a second language: Definitions and taxonomies. Language Learning, 47, 173–210. Fang, Z. (1996). A review of research on teacher beliefs and practices. Educational Research, 38, 47–65. Anne Lazaraton and Noriko Ishihara Freeman, D., & Cornwell, W. S. (Eds.). (1993). New ways in teacher education. Alexandria, VA: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. Freeman, D., & Johnson, K. E. (Eds.). (1998a). Research and practice in English language teacher education [Special issue]. TESOL Quarterly, 32(3). Freeman, D., & Johnson, K. E. (1998b). Reconceptualizing the knowledge-base of language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 32, 397–417. Freeman, D., & Richards, J. C. (1996). Teacher learning in language teaching . New York: Cambridge University Press. Gullberg, M. (1998). Gesture as a communication strategy in second language discourse. Lund, Sweden: Lund University Press. Harris, T. (2003). Listening with your eyes: The importance of speech-related gestures in the language classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 36, 180– 187. Ishihara, N. (2003). Curriculum components of the practicum in ESL. MinneTESOL/WITESOL Journal, 20, 1–20. Johnson, K. E. (1992). Learning to teach: Instructional actions and decisions of preservice ESL teachers. TESOL Quarterly, 26, 507–535. Johnson, K. E. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. New York: Cambridge University Press. Johnson, K. E. (1996). The role of theory in L2 teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 30, 765–771. Johnson, K. E. (1999). Understanding language teaching: Reasoning in action. Boston: Heinle. Johnson, K. E. (Ed.). (2000). Teacher education. Alexandria, VA: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. Johnson, K. E., & Freeman, D. (2001, May). Toward linking teacher knowledge and student learning . Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Language Teacher Education, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (2002). Inquiry into experience. In K. E. Johnson & P. R. Golombek (Eds.), Teachers’ narrative inquiry as professional development (pp. 1–14). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Johnston, B. (2001, May). Preparing reflective teachers. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Language Teacher Education, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. Johnston, B., & Goettsch, K. (2000). In search of the knowledge base of language teaching: Explanations by experienced teachers. Canadian Modern Language Review, 56, 437–468. Kamhi-Stein, L. D. (2000). Integrating computermediated communication tools into the practicum. In K. E. Johnson (Ed.), Teacher education (pp. 119–135). Alexandria, VA: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. Lazaraton, A. (2002). A qualitative approach to the validation of oral language tests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 541 Lazaraton, A. (2003). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in applied linguistics: Whose criteria and whose research? Modern Language Journal, 87, 1– 12. Lazaraton, A. (2004). Gesture and speech in the vocabulary explanations of one ESL teacher: A microanalytic inquiry. Language Learning, 54, 79–117. Markee, N. P. P. (1995). Teachers’ answers to students’ questions: Problematizing the issue of making meaning. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6 (2), 63–92. Markee, N. P. P. (1997). Managing curricular innovation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Markee, N. P. P. (2000). Conversation analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Martinez, C. (2000). Constructing meaning: A study of a teacher’s educational beliefs and literacy practices in a first grade bilingual classroom. Dissertation Abstracts International, 61(11), 4265A. (UMI No. 9993004) Mastrini-McAteer, M. L. (1997). Teacher beliefs and practices as they relate to reading instruction and student achievement. Dissertation Abstracts International, 58(12), 4601A. (UMI No. 9817730) McCafferty, S. G. (1998). Nonverbal expression and L2 private speech. Applied Linguistics, 19 , 73–96. McCafferty, S. G. (2002). Gesture and creating zones of proximal development for second language learning. Modern Language Journal, 86, 192–203. McNeill, D. (1992). Hand and mind: What the hands reveal about thought. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Moerman, M. (1988). Talking culture: Ethnography and conversation analysis. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Oskoz, A., & Liskin-Gasparro, J. E. (2001). Corrective feedback, learner uptake, and teacher beliefs: A pilot study. In X. Bonch-Bruevich, W. J. Crawford, J. Hellermann, C. Higgins, & H. Nguyen (Eds.), The past, present, and future of second language research (pp. 209–228). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press. Pavlenko, A., & Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Second language learning as participation and the (re)construction of selves. In A. Pavlenko & J. P. Lantolf (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 155–177). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1996). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Richards, J. C., & Nunan, D. (Eds.). (1990). Second language teacher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Richards, K. (2003). Qualitative inquiry in TESOL. Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan. Schegloff, E. A. (1984). On some gestures’ relation to talk. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 266–296). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Schlessman, A. (1997). Comments on Karen E. Johnson’s “The role of theory in L2 teacher education”: Reflective experience as a foundation for 542 intelligent L2 teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 31, 775–779. Shaw, P. (2002, April). Physical aspects of language teacher training. Paper presented at the 36th Annual TESOL Convention, Salt Lake City, UT. Stanley, C. (1998). A framework for teacher reflectivity. TESOL Quarterly, 32, 584–591. Stanley, C. (1999). Learning to think, feel and teach reflectively. In J. Arnold (Ed.), Affect in language learning (pp. 109–124). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stoynoff, S. (1999). The TESOL practicum: An integrated model in the U.S. TESOL Quarterly, 33, 145–151. Toohey, K. (1998). “Breaking them up, taking them away”: ESL students in Grade 1. TESOL Quarterly, 32, 61–84. The Modern Language Journal 89 (2005) Tucker, R. A., Jr. (2001). Beliefs and practices of teachers of English as a foreign language in Guiyang China middle schools. Dissertation Abstracts International, 62 (03), 886A. (UMI No. 3010126) Ulichny, P. (1996). Performed conversations in an ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 30, 739– 764. Wharton-McDonald, R., Pressley, M., & Hampston, J. M. (1998). Literacy instruction in nine first-grade classrooms: Teacher characteristics and student achievement. Elementary School Journal, 99, 2, 101– 128. Williams, S. N. (1998). The illustrated handbook of American and Japanese gestures. Tokyo: Kondansha International Ltd. Woods, D. (1996). Teacher cognition in language teaching . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. APPENDIX Transcription Notation Symbols (adapted from Atkinson & Heritage, 1984) 1. Unfilled pauses or gaps—periods of silence, timed in tenths of a second by counting “beats” of elapsed time. Micropauses, those of less than .2 seconds, are symbolized (.); longer pauses appear as a time within parentheses: (.5) is five tenths of a second. 2. Colon (:)—a lengthened sound or syllable; more colons prolong the stretch. 3. Dash (-)—a cut-off, usually a glottal stop. 4. .hhh—an inbreath; .hhh!—strong inhalation. 5. Punctuation—markers of intonation rather than clausal structure; a period (.) is falling intonation, a question mark (?) is rising intonation, a comma (,) is continuing intonation. A question mark followed by a comma (?,) represents rising intonation, but is weaker than a (?). An exclamation mark (!) is animated intonation. 6. Brackets ([ ])—overlapping talk, where utterances start and/or end simultaneously. 7. Underlining or CAPS—a word or SOund is emphasized. Forthcoming in The Modern Language Journal Larry Vandergrift. “Second Language Listening: Listening Ability or Language Proficiency?” Hiram H. Maxim. “Integrating Textual Thinking into the Introductory College-Level Foreign Language Classroom” Kim McDonough. “Action Research and the Professional Development of Graduate Teaching Assistants” Barbara Mullock. “The Pedagogical Knowledge Base of Four TESOL Teachers” Nobuko Chikamatsu. “L2 Developmental Word Recognition: A Study of L1 English readers of L2 Japanese” Yanfang Tang. “Beyond Behavior: Goals of Cultural Learning in the Second Language Classroom” Julio Roca De Larios, Rosa M. Manchón, & Liz Murphy. “Generating Text in Native and Foreign Language Writing: A Temporal Analysis of Problem-Solving Formulation Processes”