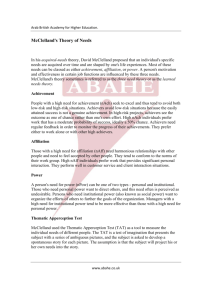

Projective Testing: Historical Overview & Thematic Apperception

advertisement