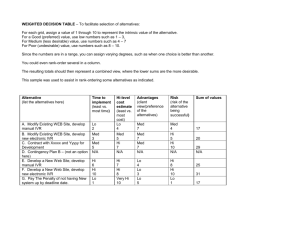

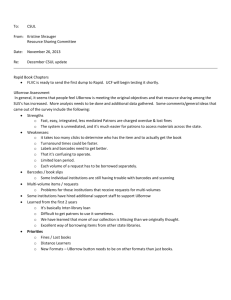

A diagnostic territorial analysis and the SWOT

advertisement