Volume 11, Special Issue, Number 1 ISSN 1544

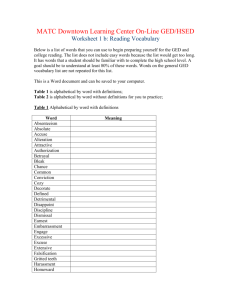

advertisement