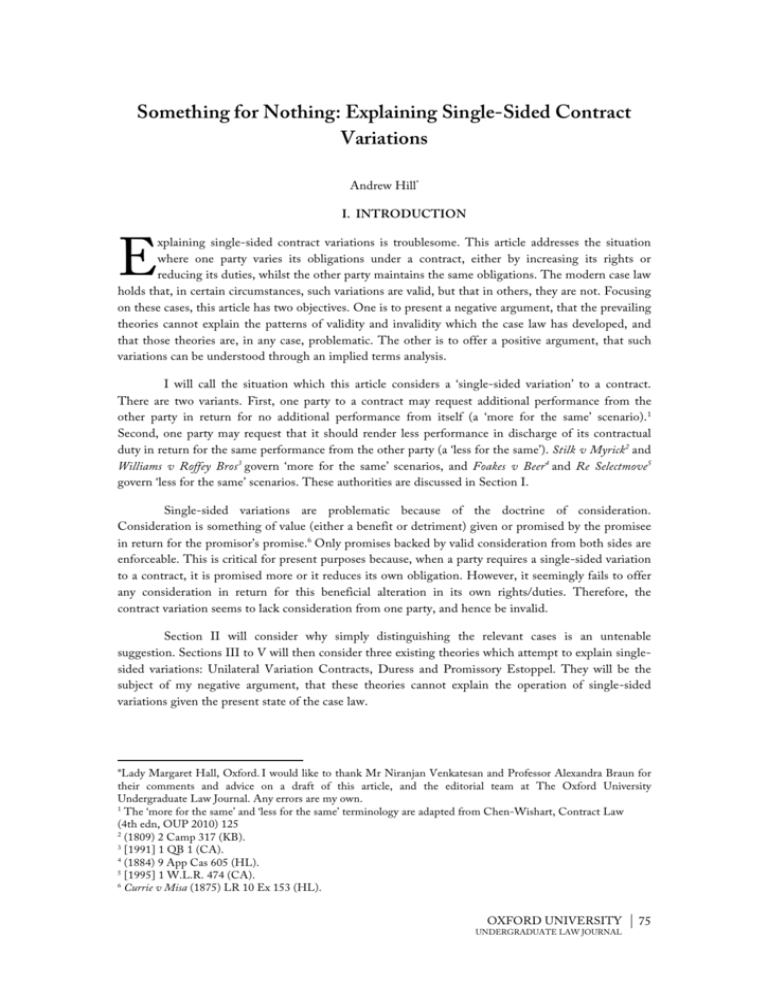

Something for Nothing: Explaining Single

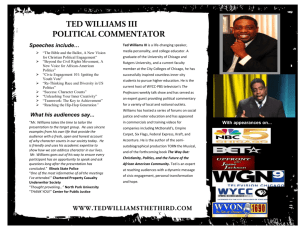

advertisement