Principled Leadership

advertisement

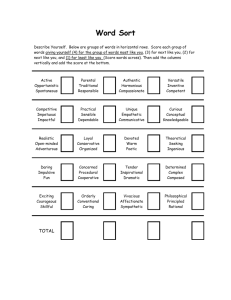

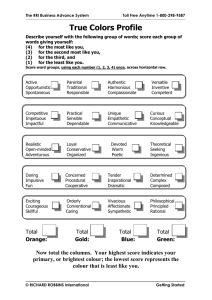

1 Bus 663 (Day Sections): Principled Leadership Fall 2005 Professor Mary Ann Glynn Teaching Assistant: Alan (Albie) Whitaker, MBA 2006 M.C. Escher, Sky and Water (1938) TENTATIVE SYLLABUS—SUBJECT TO REVISION September 13, 2005 2 COURSE OVERVIEW Today, the need for leadership, and particularly values-based, ethical, and principled leadership, is greater than ever. Corporate scandals, increased stakeholder scrutiny, and greater organizational uncertainty confront most corporations. Merrill Lynch is one advocate for such values-based leadership; they explain on their website: “By [principled leadership] we mean vigorous leadership, both by Merrill Lynch and within Merrill Lynch at all levels -- leadership that is rooted firmly in our principles, directed toward our objectives and suited to our exacting standards.” And, although the topic of leadership has a long history, examining principled leadership is quite new; this is only the second time this course is being offered at Goizueta and, to the best of my knowledge, one of the very few offerings on principled leadership in the country. In this course, we focus on how a leader’s values can create capacities for principled action. The course is designed to enhance your skills in leading with your principles, particularly in situations that challenge those principles. The Plan of the Course The course will span a broad range of approaches to principled leadership. We will focus on principled leaders who succeed and fail, as well as principled (or unprincipled) settings that can aid the success or failure of principles that leaders espouse. The course topics reflect the need for principled leaders to both be cognizant of their principles (as well as others’ principles) and to be attentive to interpersonal, social, cultural, business and organizational factors that will affect their ability to lead with their principles. Leadership has been defined as “the act of making a difference”(Useem, 1998: 4), and much of the course will be devoted to helping you get the tools you need to make a difference. But it is also important to keep the big picture in mind and to understand why, in some settings, it is more or less easy (or difficult) to make a difference. You may not be able to radically change a situation you have to work with, but understanding how it operates will help you determine where you can get the most leverage from leading with your principles. The course begins by introducing a framework for conceptualizing principled leadership and look at cases where leaders’ personal principles are clear and impactful (Class 1-3). Next, we discuss what can go wrong and how situations can overwhelm and problematize leading with principles (Classes 4-8). Armed with an understanding of how things can go wrong, we focus on making things right, and examine how leading with your strengths and principles can help you cope with those situations that challenge your principles (Classes 9-14). Then, we turn to look at how principles can enable leaders triumph over adversity and serve as a source of resilience (Classes 15-19). Finally, we conclude on a high note, affirming that principled leadership can, indeed, make organizations (and sometimes the world) a better place (Classes 20-24). 3 LEARNING OBJECTIVES FOR THE COURSE We will immerse ourselves in very complex, very real situations – through cases, stories, readings, and experiences -- where there are not easy answers, but there are good questions. Some of those questions include: What is principled leadership? What kind of principled leader am I? And how can I, as a leader, create the kinds of conditions for the "right" principles to emerge? In answering the questions, students should be able to: Explain in your own words what you mean by principled leadership Illustrate behaviors that typify principled leadership, in your judgment Discuss the implications of principled leadership for managerial dilemmas and organizational action Diagnose situational or organizational factors that work for and against your leading with principles Compare and Contrast how your leadership principles may be similar to, and different from, others with whom you interact Propose and defend a model of principled leadership, determining the pros and cons of your approach COURSE ASSIGNMENTS AND GRADING Readings My criteria for choosing the readings are that they are academically sound (i.e., based on what I know to be good research), current, and well-written. All of the readings are the best ones I know of on their topics, written by leading scholars for a managerial audience. In addition to the materials on eReserves at the Goizueta library, two books are required for this course. They are available at the University Bookstore and are quite inexpensive in paperback (about $10 - $23). They are also readily available (e.g., amazon.com; bn.com) and on reserve at the GBS library. • • The Leadership Moment, by Michael Useem (1998. NY: Three Rivers Press) Scott Snook, Friendly Fire: The accidental shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq. Princeton University. Hardcover (2000) and Paperback (2002). Cases Cases give life to the theory of principled leadership. They give us a chance to see how principles can help us (or trip us up) in difficult, real situations. The world is always more complex--and thus more interesting--than what we imagine it to be and complex situations can sometimes create blinders or challenges to well-intentioned, principled leaders. So don't be surprised or frustrated if we don't come to a single “right” answer to the case; there will always be several legitimate points of view, each with great benefits and serious flaws. 4 Although there may be no “right” answer to a case, there are weak answers that are the result of inadequate analysis. The amount you learn from a case depends on how carefully you read it and how well you analyze it. Read each case thoroughly and come to class ready to contribute to discussions, just as though you were preparing for a (worthwhile) meeting. Don't be passive; don't expect somebody else in the class to do the analysis or come up with that great solution to the firm's problems. The syllabus contains a set of study questions for each case to help you focus your preparation effort. Please read these carefully before reading a case. These will not always cover every issue, but they will give you a good basis for discussion. Assignments There are five products that compose your grade: 2 case write-ups (your choice of cases), 1 learning log (your choice), Reflected Best Self paper, and class participation (individual products) and a group paper and project. 1) Two Case Write-ups (20% total, 10% for each case write-up) You are required to submit two case write-ups. You may choose from any of the cases listed. I would recommend doing one from the first half of the course (pre-Spring Break) and one from the second half of the course (post-Spring Break). The write-ups should be typed, NO MORE THAN 3 PAGES IN LENGTH (12 pt font, double spaced, 1" margins) and consist of your answers to the Discussion Questions assigned in the syllabus. The write-ups are meant to help you develop your analytic skills and prepare you for participating in class. Your case write-up is due in class on day the case is assigned; no late write-ups will be accepted. 2) One Learning Log – Choose one option below (15%): The learning log provides you with an opportunity to reflect on the ways in which the issues and concepts raised in class affect you personally and your role as a principled leader. The questions to be answered in these logs appear below. You will have the option to select one of these logs and complete it on time – they are due on different dates -- see below. You must complete ONE of the learning logs and had it in on the appropriate date. Your learning log should be no more than 5 pages (double-spaced). I will evaluate the logs based upon how reflective, thoughtful, complete and well organized they are. Learning Log A: To trust or not to trust – DUE THURSDAY, OCT. 6th Purpose: Trust and integrity are perhaps the most critical values and principles that leaders have. In this learning log, you analyze how you lead through trusting or distrusting others1 1. Think of two people whom you know fairly well: one whom you trust, and one whom you don’t trust. 2. List the reasons that lead you to trust or distrust each person (no need to identify the real person -- use disguised names and identifying information). 1 (Modified from Paula Caproni’s “Food for thought”, in The Practical Coach 5 3. What do you do to communicate to each person that you trust or don’t trust them (i.e. what are the behaviors that you are doing that engender trust or distrust)? 4. What, if anything, could the person you distrust do to earn your trust? 5. What do you have to do to enable this to happen? What do you do, as a principled leader to win the trust of others? Learning Log B: Leadership and language – DUE TUESDAY, NOV. 8th. Purpose: “Communication is the one task that leaders can not delegate” (Roberto C. Goizueta). In this learning log, you analyze the power of language to lead with principles 1. Pick an organization with which you have been or are currently affiliated or desire to be affiliated with (can be a business or non-business organization). Find a speech or text produced by a leader, power broker or by some official body. (Hint: you can often find speeches etc. on the web for many organizations. Alternatively, you might conduct a library search on newspaper, magazines or other media sources. Attach a copy of the text to your log entry.) 2. Do an analysis of the language in the document in terms of what it implies about the leader’s (or the organization’s) principles. What do the words, images, phrases or metaphors used in the text reveal about the principles of this leader and this organization? Explain. 3. Assume you are starting your own organization from scratch. What words, images, phrases and metaphors would you see as most critical for conveying or creating a set of principles for your organization? Justify your choices. 3) Best-Self Portrait (15%) – DUE THURSDAY, OCT 27th This exercise provides you with feedback about who you are when you are at your best. You will request positive feedback from significant people in your lives, which you will then synthesize into a cumulative portrait of your "best-self." The exercise can be used as a tool for personal development because it enables you to identify your unique strengths and talents. The process of getting feedback will begin immediately and your Best-Self Portrait is due in class on Oct. 27th Your portrait should be approximately 3-5 pages in length (double-spaced, 12 pt font, 1” margins) and should focus on your interpretation of the feedback you receive. More details will be given in class. However, I strongly recommend that you start early. Your Best Self Portrait will not be evaluated on the basis of who you are, but rather on your ability to complete the exercise carefully, thoughtfully, and insightfully. I will purchase these for you and distribute them in class. NOTE: GALA students who are doing the self-assessment with Andy Fleming can coordinate the feedback for the “best self” as well as the GALA assignment. Let me know if you are interested in doing this. The RBS was featured in the January 1 2005 Harvard Business Review article, How to play to your strengths: Most feedback accentuates the negative. During formal employee evaluations, discussions invariably focus on "opportunities for improvement," even if the overall evaluation is laudatory. No wonder most executives--and their direct reports--dread 6 them. Traditional, corrective feedback has its place, of course; every organization must filter out failing employees and ensure that everyone performs at an expected level of competence. But too much emphasis on problem areas prevents companies from reaping the best from their people. After all, it's a rare baseball player who is equally good at every position. Why should a natural third baseman labor to develop his skills as a right fielder? This article presents a tool to help you understand and leverage your strengths. Called the Reflected Best Self (RBS) exercise, it offers a unique feedback experience that counterbalances negative input. It allows you to tap into talents you may or may not be aware of and, so, increase your career potential. To begin the RBS exercise, you first need to solicit comments from family, friends, colleagues, and teachers, asking them to give specific examples of times in which those strengths were particularly beneficial. Next, you need to search for common themes in the feedback, organizing them in a table to develop a clear picture of your strong suits. Third, you must write a self-portrait--a description of yourself that summarizes and distills the accumulated information. And, finally, you need to redesign your personal job description to build on what you're good at. The RBS exercise helps you discover who you are at the top of your game. Once you're aware of your best self, you can shape the positions you choose to play--both now and in the next phase of your career. 4) Class Participation (20%) Because of the interactive and developmental nature of the course, attendance and participation are critical and are an essential part of your grade. You are expected to attend each class having read all assigned readings and having prepared assignments, case questions or other discussion points. If a reading assignment is listed as a case, you should be prepared to discuss the case and answer all the assigned questions provided in the syllabus. In this course, our goal is to create an open class environment where everyone is free to comment and participate. Any behaviors that detract from the learning environment will be evaluated negatively. In class, I commit to the following and expect that you will too: 1. Be courteous. Come on time and do not leave early. Do not interrupt or engage in private conversations while others are speaking. Do not read the newspaper, do other assignments, or surf the web during class. 2. Be professional. This course is “unplugged.” Please turn off all computers, PDAs, phones, pagers, or other electronic devices during class meetings. If you need to use a computer because of a language or disability issue, you need to secure my permission at the beginning of the semester. Misusing an electronic device (e.g., surfing the Internet or messaging a classmate) will adversely affect your grade. 3. Have an opinion and respect others’ rights to hold opinions and beliefs that differ from your own. There are many different possible perspectives for interpreting the material in this class. 4. Allow everyone the chance to talk. If you have a lot to say, try to pace yourself and be judicious about how often you speak. If you are hesitant to speak, look for opportunities to contribute to the discussion. 5. Class participation will be evaluated throughout the entire course. Specifically, each person will be evaluated on a per class basis for their contribution to the class discussion of cases, readings, and related exercises. The criteria used to 7 determine the participation grade will be relevance, substance, lack of redundancy, and persuasiveness. Students who are not in class will receive no credit toward their participation grade for that day. Class participation is an important part of the learning process in this course. It is also part of what will make the course useful for you and your fellow students. Effective class comments may address questions raised by others, integrate material from this and other courses, draw on real-world experiences and observations, or pose new questions to the class. High-quality participation involves knowing when to speak and when to listen or allow others to speak. Comments that are vague, repetitive, unrelated to the current topic, disrespectful of others, or without sufficient foundation are discouraged and will be evaluated negatively. 6) Group Project: Presentation and Paper (30%) Presentations will be scheduled on the last days of the class (see syllabus); Your paper is due the last day of class, Thursday, Dec. 8th. The focus of the project is on understanding your leadership style vis-à-vis others’ principles and values. In other course assignments, such as the learning logs and the Best Self Portrait, you will (hopefully) come to understand yourself better as a leader, in terms of your values and principles and how these shape your style and enable your strength as a leader. The group project is designed to enable you to better assess your leadership orientation in the context of understanding how others lead as well as the impact you might have as a principled leader. More details will follow. Briefly, though, you will work in small groups (of about 4 students/project). As a group, you can choose either option below. You are required to present your findings in class and submit a paper (approximately 10-15 pp in length). Each student will be asked to complete a Peer Evaluation (see Appendix). Option A: Study of Principled Leaders You conduct a study of business leaders, identifying 6-10 leaders (at either national or local levels), interviewing them personally and supplementing the interviews with any archival, historical or organizational information. Following the protocol of a similar study conducted by Stanford University, your study should focus on the following 4 questions and add additional questions that interest your group: 1) How were your core values or principles shaped? 2) What is your purpose for leadership? 3) Which specific actions do you or your company take to develop "principled leaders?" 4) What are the potential benefits and costs of principled leadership? An abstract of the Stanford study is at: http://www.alfsv.org/info/page.php?id=119 Option B: Principled Leadership under crisis It seems that crises or difficulties call forth leaders, and brings out heroes and cowards. In the last few years, we have seen no shortage of crises. Recently, the impact of Hurricane 8 Katrina has been a site of success and failures in principled leadership; and, there have been many other situations, including (but not limited to): 9/11 terrorist attacks in the U.S.; the bombings in London and Madrid, as well as the American embassy in Africa; “Enronitis” (and other corporate scandals); Oklahoma City; and local, national, and public responses to natural disasters such as the tsunami and hurricanes. To prompt your ideas, here are some possibilities that could lead to projects (although you’re not limited to these), along with some mentions of the issues in the press (but your project should go considerably beyond these cites): o Hurricane Katrina: Responses by the New Orleans police department to the immediate impact of the hurricane (See for instance, interview with New Orleans Police Chief on “60 Minutes,” 9/11/05). o Flight # 93: Choosing courageous action (See for instance, the upcoming Discovery Channel piece, “The Flight that Fought Back”) o 9/11 Aftermath: How do we value human life and suffering? What principles guide our compensation decisions? (See for instance, Kenneth Feinberg’s book, What is Life Worth?: The Unprecedented Effort to Compensate the Victims of 9/11) o And, closer to home, perhaps social entrepreneurship in Atlanta (e.g., working with East Lake Community and their leaders to address their concerns). As a group, you will need to choose a recent, visible, public crisis and focus on one key aspect (portion) of that crises. Locate publicly available information on this aspect of the crisis, through the internet, newspapers, magazines, books, etc. (and, if possibly, contacting any of those involved in the crisis). Focus on understanding how principled leadership is effective, ineffective and/or absent in the situation. Examine: - What principles are evident in the crisis? What principles are missing? - Where does principled leadership occur? And where is it missing? Be sure to examine: o Individual leaders, both formally appointed and informally emergent o Organizational, governmental (local, national), societal, cultural, and other systems that may function to support (or not support) principled leadership and action - Why is this so? Why does principled leadership emerge where it does…and why is it absent when perhaps it should be working? - From your analysis of principled leadership in this crisis situation, develop your personal framework for principled leadership, along with a set of tools for principled leadership. How can you use your values and principles to be helpful in a time of crisis? Note: All written work should be typed, with reasonable fonts (e.g., 12 pt Times New Roman or equivalent) and margins (1" all around). Keep a back-up copy of all assignments. No folders or binders around your paper are needed, but a cover page, identifying yourself, the assignment, and your course section is useful. 9 Grading Distribution Course grades will follow the required distribution for Goizueta’s MBA elective courses: DS 20%, HP 40%, PS 40%, and other grades as needed. GBS LIBRARY & COURSE MATERIALS Required readings are available through eReserves Direct, which is accessible through the GBS Library at: http://business.library.emory.edu/ At the website, under Quick Links (on the right), click on Reserves Direct. Select instructor’s name (Glynn) and course (BUS 663).You login with your OPUS ID; non-GBS students enrolled in the course should have access. The Goizueta help line (727-0581) can assist with technical problems. Additionally, you’ll need to purchase HBS cases through Study.Net at www.study.net . 10 OUTLINE OF CLASS TOPICS Fall 2005 Class Day 1 Tues Recommended not required Wed Date Guest Speaker Topic (See Syllabus for details) Introduction to Principled Leadership 13-Sept 14-Sept The Honorable Shirley Franklin, Mayor of the Emory Dept. of Women’s Studies Colloquium Series On “Women, Power, and Social Change” City of Atlanta at Emory U., White Hall 101 at 4 p.m. I. PERSONAL VALUES AS PRINCIPLES FOR LEADING 2 Thurs 3 Tues 4 Thurs 15-Sept 20-Sept 22-Sept Case: Roy Vagelos at Merck (Useem book) GBS Case: Martha Stewart (class conference) Zimbardo Prison Experiments II. PRINCIPLES AS PROBLEMS: LIFE, DEATH AND PRINCIPLED LEADERSHIP 5 Tues 6 Thurs 7 Tues 8 Thurs Tues 27-Sept 29-Sept 4-Oct Case: Wagner Dodge at Mann Gulch (Useem book) Case: Pinto Fires (eReserves) Friendly Fire I (book & video): Luke Ott (pilot) Optional: 6-Oct Learning Log A due Friendly Fire II: How could it happen? 11-Oct *** Fall Break *** No Class III. PRINCIPLES AS PROBLEM SOLVERS: RECOVERY & RESILIENCE 9 Thurs 10 Tues Recommended not required Wed 11 Thurs 12 Tues 13 Thurs 14 Tues 15 Thurs Prof. Queen, 13-Oct Emory/Ethics 18-Oct Julie Gerberding, 19-Oct Director, CDC 20-Oct 25-Oct Servant Leadership, with Prof. Ed Queen, Emory Managing Value Conflict: 12 Angry Men, Part I Emory Dept. of Women’s Studies Colloquium Series On “Women, Power, and Social Change” at Emory U., White Hall 101 at 4 p.m. Managing Value Conflict: 12 Angry Men, Part 2 HBS Case: Martha McCaskey Leading with your strengths: Reflections on your Best Self, with Brandon Smith, Executive Coach HBS: George McClelland Case: Eugene Kranz (Useem book) 19 Thurs 27-Oct RBS paper due 1-Nov 3-Nov Optional: 8-Nov Learning Log B due MLK, Letter from a Birmingham Jail 10-Nov HBS Case: Taran Swann at Nickelodeon Social Entrepreneurship: How principled leadership 15-Nov can change the world GBS Case: East Lake Community, 17-Nov With Carol Naughton (Director) 20 Tues Thurs 21 Tues 22 Thurs 23 Tues 24 Thurs 22-Nov 24-Nov *Thanksgiving * 29-Nov 1-Dec 6-Dec 8-Dec Project Paper due 16 Tues 17 Thurs 18 Tues IV. How Principled Leadership Matters TBA No Class TBA Presentations Presentations Last Class: Wrap-up Note: Dates for Guest Speakers are subject to change, depending upon their schedules. 11 CLASS ASSIGNMENTS Class # 1: Introduction Assignment Questions: What is your definition and model of principled leadership? What is your purpose for leadership? Please be prepared to share your ideas in class. I. PERSONAL VALUES AS PRINCIPLES FOR LEADING Class # 2: Personal principles resolve a managerial dilemma Readings: Read at least one of the following for the skeptical view: from The Economist, Jan 20th, 2005 (on eReserves) • A skeptical look at corporate social responsibility • The ethics of business • The world according to CSR And, for balance, read: Tichy, McGill & St. Clair, “Corporate Global Citizenship” Prepare Case: Useem, Chapter 1: Roy Vagelos attacks river blindness (pp 10-42) Optional: On Merck’s recent troubles (Vioxx), see http://www.cbc.ca/story/science/national/2005/01/25/vioxx-050125.html Read more about it: Roy Vagelos and Louis Galambos. 2004. Medicine, Science, and Merck. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Discussion questions: 1. Should Dr. Vagelos have funded the river-blindness research? Take a position –pro or con -- and be prepared to defend it, using insights from the readings and case evidence from the Useem chapter. 2. What criteria should owners and managers use to make decisions in setting goals for their organizations: profitability? social impact? a combination of these? other criteria? 3. What role should (does) ethical principles play in leadership? Class # 3: Personal principles become the managerial dilemma Prepare Case: Martha Stewart (Distributed via class conference) Discussion Questions: 1. Answer the question implied in the title: Is Martha Stewart a principled leader? Why? ? 2. What criteria are you using to determine if Stewart, as a leader, is principled? How do you evaluate the values and principles espoused and displayed by Stewart to determine if they are good are bad, appropriate or inappropriate? 3. To whom is Stewart accountable? To whom should leaders’ principles apply? 12 Class # 4: When principles create their own dilemma Reading: Note on Human Behavior: Character and Situation # 9-404-091 Stanford Prison Experiment (Philip G. Zimbardo) Update: http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,3604,638243,00.html Discussion Questions: 1. How do you make sense of the behavior of the Stanford students involved in the Zimbardo experiment? What were the key features of the experiment that influenced the behavior observed? Under what circumstances might the behaviors have been different? 2. In the Milgram experiments described in the reading, how much weight would you place on the character of the persons involved and how much on the situation? 3. Have you been in a situation where you felt that you were behaving in a manner that was at odds with your true character? What was it about the situation that influenced your behavior? 4. In contrast, have you been in a situation where the strength of someone’s character allowed others to rise above the strong influence of the situation? II. PRINCIPLES AS PROBLEMS: LIFE, DEATH AND PRINCIPLED LEADERSHIP Class # 5: Principles on fire: Prepare Case: Useem, Chapter 2: Wagner Dodge Retreats in Mann Gulch Reading: Weick, Karl – Articles on eReserves OPTIONAL: Weick, Karl. 1993. “The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 38: 628-53 Class # 6: Principles under fire Prepare Case: Gioia, D. A. "Pinto Fires and Personal Ethics: A Script Analysis of Missed Opportunities." Journal of Business Ethics 11 (1992): 379-389. Reading: When Good People Do Bad Things at Work http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v10n2/peopleatwork.html Classes # 7-8: Principles under the gun The next 2 classes will focus on Scott Snook’s book, “Friendly Fire…” Assignment: The book focuses on explaining how the tragic accidental shootdown of the Blackhawk helicopters by F-15 fighter pilots could have occurred. The breadth of 13 explanation is wide-ranging, from individual (Chapter 3), to groups (Chapter 4) and organizational systems (Chapter 5). It might seem incredulous that this could have happened to principled, well-intentioned, and highly capable individuals … but we’ll have a pilot, Luke Ott, as our guest speaker, to help us sort it out. I’d encourage you to read the book and particularly chapters 3, 4, and 5. But, I realize your time is limited and so we’ll focus in class primarily on chapter 3; please read that one carefully and skim as much of the others as you can. As you finish each chapter, close the book and reflect on what you’ve read, asking yourself: Who was responsible for those 26 deaths? Then, try to shift your thinking from “Who/What caused this accident?” to “What set of conditions increased the likelihood of this accident?” More generally, ask yourself: Under ambiguity, what do you look to for guidance? Are there principles that drive your action and leadership in challenging situations? Reading: Focus on the Introduction through Chapter 3, Individual-Level Account (pp 1-96). Read what you can of the rest. III. PRINCIPLES AS SOLUTIONS: RESILIENCE & RECOVERY Class # 9: Servant Leadership, with Prof. Edward Queen, Emory Ethics Readings: TBA Classes # 10 and 11: Managing Values Conflict & Prioritizing Principles Readings: Cialdini, “Harnessing the Science of Persuasion” Conger: The Necessary Art of Persuasion Snyder, “Self-fulfilling stereotypes” In-Cass Video Case: 12 Angry Men Video (1957) – 2 parts http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0050083/combined Discussion Questions: 1. What are the basic options that Davis has when he enters the jury deliberations? 2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of his alternatives? Class # 12: Resolving Conflict between Personal & Organizational Principles Prepare Case: Martha McCaskey (HBS # 9-403-114) Reading: Personal Values and Professional Responsibilities Discussion Questions: 1. How serious is the situation with the Silicon 6 project? 2. As Martha McCaskey, what would you do? 3. Was McCaskey’s situation avoidable? If not, why not? If so, what might be done to avoid it? 14 Class # 13: Strength-based, principled Leadership Reflections on your Reflected Best Self, with Executive Coach Brandon Smith DUE: RBS paper Class # 14: Passing the “Sniff Test” – Can Principles be early warning systems? Prepare Case: George McClelland at KSR (A) (HBS # 9-403-163) George McClelland at KSR: Planning the First Week Discussion Questions: 1. As George McClelland taking charge of this company, what are your top priorities for the coming year? 2. As George McClelland, how would you spend your first week on the job? Please fill out the weekly planner (“George McClelland at KSR: Planning the First Week”) and bring it to class. Class # 15: Principles Rule: “Failure is not an Option”! Prepare Case: Eugene Kranz (Useem book)(On your own, you might also view “Apollo 13” where you’ll see Eugene Kranz at work!) Readings: TBA Class # 16: Prisons and Principles Readings: 1) Letter from a Birmingham Jail (on Reserves or at http://almaz.com/nobel/peace/MLK-jail.html 2) “Every leader tells a story” by Elizabeth Weil. Available on FastCompany: http://www.fastcompany.com/online/15/rftf.html 3) “What’s your story?” (HBR Jan 1 2005 – Ibarra) Optional: Visit the MLK National Historic Center in Atlanta, minutes away http://www.nps.gov/malu/ Discussion Questions: 1) What is the relevance of Dr. King’s ideas for executives and managers? 2) How does Martin Luther King tell his story? How does this compare with yours? (Refer to your Leadership Narrative, from the first class, and/or your Reflected Best Self (RBS) Portrait). 3) What principles underlie these stories, both yours and MLK’s? How do they compare? What story do you want to tell as a principled leader? Class # 17: Principles at Work and in Life: Case: Taran Swann at Nickelodeon Latin America (HBS (A) 9-400-036) Discussion Questions: 1. Describe the culture at Nickelodeon. Be specific. 15 2. 3. 4. How did Swan go about building that culture? (Consider the interrelationships among Nickelodeon’s context, design factors, culture and outcomes.) Describe Swan’s leadership style. What impact has it had on the culture? What are the challenges that Swan faces at the end of the case? What actions should she take? Class # 18 and 19: Social Entrepreneurship Readings: Chapters from David Bornstein, How to change the world Prepare Case: East Lake Community in Atlanta, GA (To be distributed) With Carol Naughton, Director Classes # 20 and 21: TBA Classes # 22 and 23: Presentations of Group Projects Class # 24: Wrap-up and Summary. Project Papers Due 16 Appendix: PEER EVALUATION FOR YOUR GROUP PROJECT (to be submitted at the last class) MY TEAM PROJECT/TITLE IS _________________________________________________ Please evaluate the relative contributions of other members of your team to your project. Consider each team member’s contribution overall, to all aspects of your project, including, but not limited to: project conceptualization, analysis, and execution; group discussions; research; preparation and/or delivery of in-class presentation; preparation and writing of paper; etc. Remember that your team has been actively involved in your project for the entire course, so be sure that your evaluation represents your assessment of behavior over the entire time. Now, evaluate the other students on your team as to their overall contribution to your project, choosing either Option A or Option B (below). Option A: I feel that all members of my team contributed equitably and fairly to the project. We may not have all done the same work, but I feel that we all contributed about the same amount. Therefore, I feel that we should all be awarded the same grade for the project. If you chose this option (A), SIGN HERE: _______________________________________ Please PRINT your name here: ________________________________________________ Option B: I feel that not all members of my team deserve the same grade for the project. Therefore, I am rating the other students on my team in terms of their overall contribution to the project. Rate each of your team members below, using a scale from 1 to 100, with 100 being the highest. The ratings that each student receives, standardized across all members’ ratings, determine their relative contribution and may affect their grade for the project. PRINT the names of your team members: Rating (1 to 100): _____________________________________________ ____________ _____________________________________________ ____________ _____________________________________________ ____________ _____________________________________________ and your name here: ____________ Rate yourself: _____________________________________________ ____________ Briefly explain any large differences in team members’ ratings (above). In other words, why did you rate this person much higher or much lower than other team members? (Use the other side of the page, if necessary.) If you choose Option B, SIGN HERE: _______________________________________