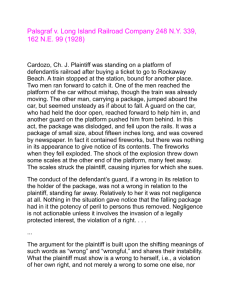

Chapter 2 Proximate Cause

advertisement