INTEGRATING GIFT CARDS INTO THE ACCOUNTING

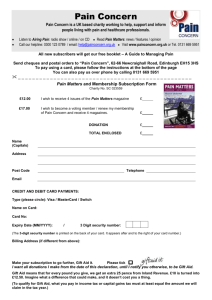

advertisement

INTEGRATING GIFT CARDS INTO THE ACCOUNTING CURRICULUM Ronald R. Rubenfield Associate Professor of Accounting Robert Morris University (412 262-8301 rubenfield@rmu.edu Accounting Track (Refereed research paper) INTRODUCTION Gift cards have become an increasingly popular way of conducting business. Tower Group estimated that $97 billion was spent on gift cards in 2007. [2] Although this figure was expected to decline to about $88.5 in 2008 it still represents a sizeable portion of the retail industry. [2] Since many students are familiar with these cards accounting instructors have a unique opportunity to enhance students’ comprehension of both business and accounting concepts. This paper will discuss the two types of gift cards, review gift cards in comparison to other ways of transacting business and explain the accounting for these cards. The paper concludes by offering suggestions for the effective use of these and for establishing a more consistent accounting for them. Types of Cards: Retail v. Bank Perhaps the best introduction to gift cards is to first discuss the ubiquitous debit card that most students are very familiar with. The debit card, although misnamed, is really the same as paying cash or issuing a check. Money is in the user’s account and withdrawn immediately upon authorization. The user authorizes a deduction either by signature or by identification number (PIN). The business is assessed a fee so it does not collect the full proceeds of the transaction but does have immediate access to the cash. Of course, from an accounting point of view, the user’s cash account is reduced, or credited, thus giving rise to the inaccurate term for the transaction. With this context established the instructor can move to a discussion of the more complicated and contentious gift cards. There are two popular types of gift cards, retail and bankcards. Both are pre-loaded with cash thus their similarity to debit cards, Retail, or close-looped, cards are by far the most popular but bankcards are catching up. Retail cards are purchased from a specific retailer and can be used only at that establishment thus giving rise to their closed-looped or limited nature. Bankcards, on the other hand, have greater flexibility and can be used virtually anywhere like a bank credit card. In 2008 it was estimated that $60 billion was spent on retail cards which represented a 14.4% decline from the previous year. [2] Bankcard use for the same period was estimated at $28.5 billion representing a 5.6% increase from 2007. [2] Obviously the recession has taken its toll on all businesses but has hit retail cards particularly hard. Perhaps consumers are concerned about the potential bankruptcy of certain retailers and have curtailed their purchases of these cards thus exacerbating the decline. How does using gift cards stack up with other ways of doing business? Transacting Business Merchants can engage in business transactions for cash, charge cards or, the increasingly prevalent, gift cards. A cash transaction provides an immediate exchange of assets and except for the possibility of a return the business cycle is complete. The merchant has the cash and the customer the goods or services. It is a business neutral transaction. If the customer uses a charge card the goods or services are received before payment is made. The consumer gains an advantage (float) if the liability is paid in a timely fashion. If cash is not paid when due interest accrues at a high rate and the merchant (or bank) benefits if the cash is ultimately collected. Of course, there is the possibility of incurring a bad debt if the merchant provides the financing or being assessed a service charge if a bank credit card, such as VISA, is used. The retail gift card transaction is the most advantageous transaction for the merchant. The merchant receives cash prior to earning it and the possibility exists that the card may never be fully redeemed (breakage) making it a seemingly ideal way to conduct business. In addition the money is immediately available to earn interest. With a bankcard the user initiates a transaction, similar to using a debit card, and the money is withdrawn from the available cash and transferred to the merchant. Unlike a retail card there is typically an up-front service charge to the purchaser of a bankcard. We now look at how gift card transactions are accounted for. Gift Card Accounting A brief review of the revenue recognition principle would be helpful before the discussion of gift card accounting is undertaken. Revenue recognition, of course, occurs when a transaction is complete and the collection of an asset is reasonably assured. Normally this occurs when a product is delivered or a service rendered and a charge card or cash is given in consideration. The revenue is typically recorded at the point of exchange whether or not cash is received at that time. With a retail gift card the merchant receives the cash before delivering a product or rendering a service. This transaction establishes a liability (unearned revenue) for the merchant. When the obligation is “paid” with the delivery of a product or rendering of a service the liability is reduced and revenue is recorded. With a bankcard, when a card is used, the merchant treats it as a cash transaction similar to a debit card accounting and the bank reduces its liability. The above transactions are routine and non-controversial. However it is the non-use of these cards and related service fees that can be problematic for their users. Breakage and Service Fees It is impossible to accurately gauge how much gift card breakage occurs. It is up to the business to self-report breakage in its annual report if one is required. Private companies, of course, have no requirement to provide any financial activity to the public. TowerGroup estimated that unredeemed gift cards totaled almost $8 billion in 2006. [1] In its survey for 2006 Consumer Reports found that 27% of recipients had not used at least one card, up from 19% in 2005. [1] Whatever the actual amount, suffice it to say, breakage is large and growing with increased gift card use. Related to the potential for breakage are service charges and expiration dates. Bankcards, unlike retail cards, almost always carry up front service charges to the purchaser. A common charge might be $3 for any card with a value of $10-$1000. For example a $50 card would be purchased for $53. In addition most bankcards will assess another fee for non-usage after a certain period of time typically six months. This, of course, de facto establishes a time limit on usage, as eventually unused cash will be exhausted. So the sponsoring bank can derive revenue in three ways: from interest by investing the money before payouts are authorized, from up-front charges and from nonuse fees. While these revenue opportunities seem to be somewhat exploitative for a no risk, low-cost service that the bank is providing all must pass the scrutiny of bank regulators. Retail cards can also assess non-use charges and establish time limits on usage but the practice has become less common. Perhaps pressure from state governments, including applying escheat law, has discouraged these practices. Indeed in a survey of fifteen large retailers, the author did not find one that still maintained a service charge or expiration date. [4] Several had recently eliminated one or both of these practices. Accounting for Breakage As mentioned above there is little controversy involving the sale and redemption of the retail gift card. The contentious issue is when to book the expected breakage and an appropriate amount. No specific Generally Accepted Accounting Principle (GAAP) has been issued to clarify the issue. The only general guidance comes from the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) Pamela Schlosser who indicated, at an American Institute of Certified Public Accountants’ conference in 2005, that income recognition at the time the card is sold is not appropriate [5]. She went on to add that it was her staff’s previous view that it would be appropriate to recognize revenue when “the vendor is legally released from its obligation” to deliver the goods or services or “at the point redemption becomes remote” [5]. No further guidance is given and no specific accounting standard has been issued regarding breakage. The author did find that eight of the fifteen companies surveyed used “remote” to describe the threshold for recognizing breakage income. [4] When mentioned, the “remote” period varied up to 60 months from the purchase of the card. [4] Clearly the accountant, in determining the recognition threshold, must use professional judgment. Historical evidence should be prioritized. Accounting instructors can relate this adjustment to the one involving bad debts. The accountant uses an aging analysis or a historical percentage to determine the appropriate write-off for bad debts. Similarly with breakage, accountants would use past experience regarding the non-use of retail cards in determining the amount of breakage to record. If this amount is material the opportunity for earnings management exists. A class discussion of the materiality concept might be appropriate at this point. For example, in 2005, Home Depot opted to record $43 million from estimated breakage in previous years [3]. Since this was the first year of recognizing any breakage Home Depot recorded the accumulated amount for all prior periods that the retail card was available. It added another $9 million for estimated 2005 breakage. [3] Are these amounts material enough to warrant skepticism on the part of the auditor or investor? Could income have been manipulated by overestimating breakage? How much did this adjustment affect this period’s earnings per share? Also, Home Depot disclosed these amounts not as additional revenue but as a reduction in selling, general and administrative (SGA) expense [3]. Obviously, this accounting treatment was conveyed in its annual report. Since no GAAP exists for gift card accounting other companies may not be as forthcoming as Home Depot. Indeed Kile’s research indicated that only 39 companies (23%) disclosed any gift card revenue on the income statement [3]. So how should breakage be disclosed? And what might a standard for gift card accounting look like? This presents the instructor an opportunity to discuss the need for a possible standard for gift card accounting. The following points could be the basis for this discussion. Toward Consistent Breakage Accounting The amount of the earnings recognition for previous years’ breakage and for the current year, if material, should be disclosed and explained in the footnotes. If a separate account is not provided for breakage revenue the footnote should explain what account is used. The best conceptual approach would be to show it as an operating income item as part of sales. In essence, breakage is the additional charge for goods that were redeemed with the gift card. It certainly is not related to SGA expense as recorded by Home Depot or to cost of goods sold since nothing was sold. Furthermore it does not meet the criteria for an extraordinary item (unusual and infrequent) or an unusual item (unusual or infrequent) so it should not be disclosed as such. As far as the time period to wait to recognize breakage revenue a reasonable period would seem to be two years. The de facto breakage period (when the probability for redemption becomes remote) is likely less than two years so this would be a conservative approach and is consistent with current tax law. If an amount is redeemed in a later period it could be reversed out much like occurs when a bad debt previously written off is ultimately collected. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION Instructors have a unique opportunity to integrate gift cards into the accounting curriculum to enhance students’ understanding of business and accounting concepts. The most important financial issue for businesses and consumers is that some of the cards’ value will likely go unused thus giving rise to the concept of breakage. The business thus has extra income potential everytime a gift card is purchased. And virtually the only cost to the business would be for the purchase of a card reader which typically sells for around $500. Recipients of gift cards should therefore use these cards promptly to avoid breakage or service fees for non-use. As for the accounting for gift cards, instructors have an opportunity to reinforce the important revenue recognition rule. In addition the instructor can discuss the potential need for a standard involving the recording of the estimated breakage revenue because the accounting for gift cards varies widely. A comparison with the accounting for bad debts can be used to establish the context for establishing or applying an appropriate standard. In conjunction with this discussion concepts such as materiality and extraordinary items can also be reviewed. With gift cards playing an increasingly large part of business transactions some discussion of this concept is appropriate in the introductory or intermediate accounting courses. The students already have the personal experience with these transactions. It would seem routine to add it as a component to the accounting curriculum to both stay current with modern business practices and to comprehend how to account for gift card transactions. REFERENCES 1. Anonymous. Consumer Reports Takes on Gift Cards in Second Annual Public Education Campaign [online]. www.consumersunion.org/pub/core_financial_services/ous188.html. 2. Anonymous. TowerGroup Press release [online]. www.towergroup.com/research/news/news.htm?newsId=4940 3. Kile Jr., C. O. (2007). Accounting for Gift Cards. Journal of Accountancy, November: 38-43. 4. Rubenfield, R. (2008). Survey of fifteen public companies. 5. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Statement by SEC Staff: Remarks Before the 2005 AICPA National Conference [online]. www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch120505ps.htm.