Understanding the Income Statement

advertisement

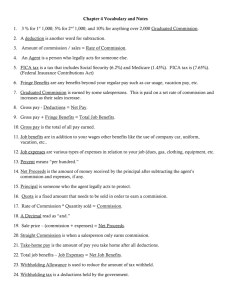

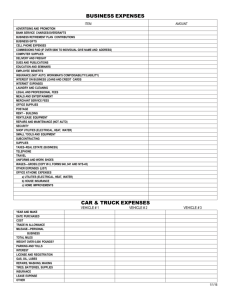

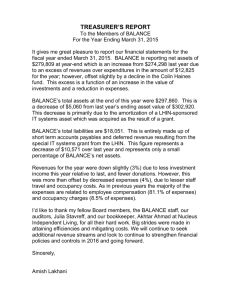

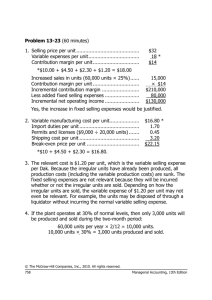

Understanding the Income Statement The Income Statement is a valuable as a business management tool and necessary for financial reporting. It is vital to the accurate calculation of direct Cost of Goods or Services and as well as the business taxes payable to the Canada Revenue Agency. An Income Statement could be produced for any period of time such as a month, quarter or a year. At the very least, a yearly Income Statement is required in order to calculate the amount of personal or business tax owing. Note: an Income Statement could also be referred to as a “profit and loss statement” or a “statement of business activities”. In this document, the term “income statement” will be used. Structure of an Income Statement and general definitions: 1. Revenues – all company earnings 2. Direct Cost of Goods Sold or cost of service: all expenses that go directly into producing a product (ie: furniture manufacturer), purchase cost of retail goods (ie: clothing store inventory or in delivering a service (plumber wages) 3. Gross Profit: Revenues less Direct expenses equal the Gross profit of a company. The Gross Profit is also reflected as a percentage of revenue and is called the Gross Profit Margin. 4. Operating Expenses – all other expense required to operate the business 5. Net Profit and Net Profit Margin 1. Revenues The first component of an Income Statement is the summary of the revenue or sales that the business has achieved during the period. Revenue lines should be set up to accurately reflect business ‘divisions’ or key revenue activities. If a business sells product and offers a service, these should be distinct revenue lines within the Income Statement. seIf you are using an accrual based accounting system, as many accountants and bookkeepers do, this revenue summary could include sales that you have made and invoiced your customer for, even if you have yet to be paid. In this case, that outstanding amount appears on your balance sheet as an Account Payable (see BBA Guideline – Understanding the Balance Sheet). 2. Expenses Expenses should be divided into two main categories, Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) for manufacturers and retailers or Direct Cost of Service for service based businesses, and General Operating expenses. Basin Business Advisors Program Business Guidelines: Understanding the Income Statement Page 1 a) Direct Cost of Goods Sold or Cost of Service (COGS) COGS may be referred to as variable costs, and are those expenses that will increase or decrease as the volume of your business increases or decreases. Some examples are: • Raw material and associated transportation costs. • Employee labour involved in manufacturing a product or in delivering a service. • Fuel. Often when preparing year-end income statements, an accountant will calculate the correct Cost of Goods Sold for that year by taking into consideration beginning and ending inventory as well as the value of product purchased during the year. The following retail store example may help to demonstrate: Beginning Inventory Value (Jan 1). = $22,000 Purchases (Jan 1 – Dec 31) = $110,000 Ending Inventory Value = $35,000 COGS = $97,000 In this example, the store will show a real $97,000 Cost of Goods Sold (22,000 + 110,000 – 35,000) on its year-end income statement. This is in fact the value of retail product sold, and is very important in determining the gross profit margin that the store is able to achieve. The real cash outlay was actually $110,000 or $13,000 more than the COGS. This is because the value of inventory at the end of the year was higher than the start of the year. This could happen due to a number of valid reasons such as: • The beginning inventory (Jan 1 ) was too low. • The end of year (Christmas) sales were not as high as expected, therefore the store was heavy st st on product on Dec 31 . • A store expansion took place during the year, resulting in a need for additional product. Gross Profit Dollars and Gross Profit Margin Gross Profit is the difference between the revenues, and the COGS expenses. Gross profit is the money that a business has left to cover operating expenses as well as contribute to the business’s net profitability. Gross Profit is given in dollars, or as a percent of the total revenues, which is referred to as Gross Profit Margin. In the example supplied at the end of this document, the Gross Profit dollars are $38,586, while the Gross Profit Margin is 41%. Knowing your businesses gross profit margin is a very useful tool. In this example, the owners knows that 41% of the work done, or $410 of every $1,000 in revenues, may be available to help pay the operating or fixed costs. Basin Business Advisors Program Business Guidelines: Understanding the Income Statement Page 2 Operating Costs Operating costs, sometime referred to as fixed costs, are those which will not vary much based on the volume of business or revenues that a business does during a period. Some examples are: • Insurance. • Manager’s salary. • Advertising and promotions. • Internet and telephone. • Building or equipment leases. • Mortgage and other long term debt payments. • Utilities (unless perhaps involved in large scale production where a power value can be assigned to the hourly use of a piece of equipment). It is important to note that the there may be a difference between the operating expenses reported in the income statement, and the actual cash that the business paid out during the same period. This may be due to Canada Revenue Agency’s definition of allowable expenses on an income statement, which is then used to calculate business or personal taxes owing. Some examples of are: False Expenses An income statement can contain “false” expenses, such as Depreciation or Capital Allowance. Depreciation is a method that the CRA allows a business to use in order to reduce the value of assets (vehicles, buildings, equipment) over their useful lifespan. Differing types of equipment may be depreciated at different rates, depending on CRA rules. As an example, your accountant may depreciate a $10,000 piece of production equipment over five years using a straight line calculation. This means that you could realize a $2,000 depreciation expense each year ($10,000 / 5). This is beneficial as it will reduce the company’s net income $2,000 for that year, thereby reducing taxes payable. This is however a false expense, as your company did not actually pay out $2,000 during the year. The equipment may have been paid for in previous years, or it may be financed over subsequent years. Expenses Not Considered Another scenario is the various cash outlays that are not included in the allowable income statement expenses. Included in this category are: 1. Principal Debt Repayments. The CRA allows for the interest portion of debt payments to be included as an expense on an income statement, but not the principal portion of that payment. As an example, your business may have purchased a $40,000 truck, which is financed over six years. The combined principal and interest payments could be $640 per month, or $7,680 per year. Of this yearly cash outlay only about $920 would be in interest payments in year four. The remaining $6,760 that the business actually paid out in principal payments may not be captured on an income statement. Basin Business Advisors Program Business Guidelines: Understanding the Income Statement Page 3 2. Capital Expenditures financed through Cash Flow Often if the business appears to running well, an owner may decide to pay for building upgrades or the purchase of a new piece of equipment rather than finance and repay a loan over time. Although the money outlay has happened in the first year, an accountant could still depreciate these capital assets over time. As an example, a business owner that is leasing a large retail space may decide to replace the floor at an expense of $25,000. This $25,000 expense could be considered a leasehold improvement on a balance sheet, and then be depreciated over time as discussed with the piece of equipment or the truck used in the examples above. The actually cash outlay which all happens in year one would not however be captured in the income statement, with the exception of the first year depreciation value. Net Profit Dollars and Net Profit Margin Net profit dollars are the real profit of a business before corporate or personal income tax is paid. Like gross profit, net profit can also be expressed as a percent of total revenue, and is then called Net Profit Margin. In the example supplied, the Net Profit dollars are $8,321 while the Net Profit Margin is 9%. As stated at the beginning of this guide, the income statement is a necessary financial reporting tool, and is vital in accurately calculating the Cost of Goods Sold as well as the business taxes payable. It may not however be a good indicator of the actual money flowing into and out of your business. A business with a positive net income may still have a negative cash flow, thus causing that business to become insolvent. Please see BBA Guideline – Understanding the Cash Flow Statement. An example of an Income Statement follows on the next page. Basin Business Advisors Program Business Guidelines: Understanding the Income Statement Page 4 Jim's Bait Shop - Income Statement Full Year REVENUES Live Bait $ 8,825 Tackle & Misc $ 17,200 Rods $ 67,000 $ 93,025 Live Bait $ 3,089 Tackle & Misc $ 7,000 Rods $ 33,000 Wages (staff excluding owner) $ 11,350 TOTAL COST OF GOODS SOLD $ 54,439 GROSS PROFIT DOLLARS $ 38,586 TOTAL REVENUES COST OF GOODS SOLD GROSS PROFIT MARGIN 41% OPERATING EXPENSES Advertising $ 2,050 Amortization - Equipment $ 7,500 Bank charges $ 600 Busines tax, fees, licences, dues $ 150 Telephone $ 1,800 Truck Loan - Interest Payments $ 920 Rent $ 13,200 Legal, accounting and other professional fees $ 1,130 Maintenance & repairs $ 600 Office exp $ 300 Utilities - Electric $ 540 Utilities - Natural Gas $ 1,475 TOTAL OPERATING EXPENSES $ 30,265 NET PROFIT DOLLARS $ 8,321 NET PROFIT MARGIN Basin Business Advisors Program Business Guidelines: Understanding the Income Statement Page 5 9%