Pied Beauty - divaparekh

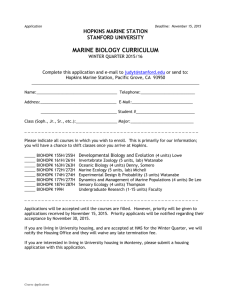

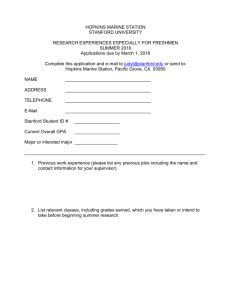

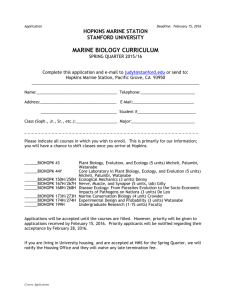

advertisement