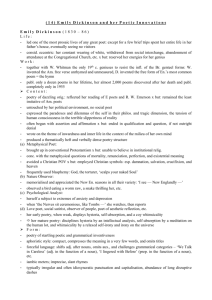

Poetry in The Post - Newspaper In Education

advertisement