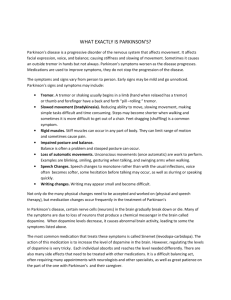

What You and Your Family Should Know new

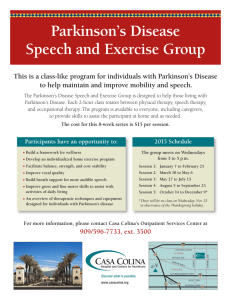

advertisement