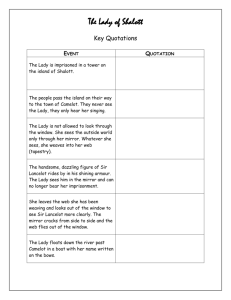

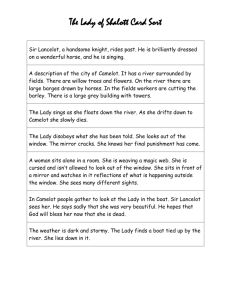

Cracked mirrors and petrifying vision: negotiating femininity as

advertisement