Tennyson's Poetics: the Role of the Poet and the Function of Poetry

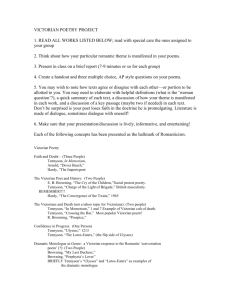

advertisement