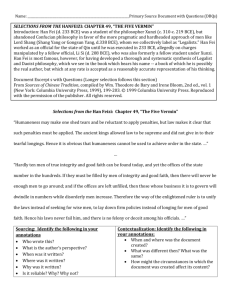

A Spring That Brought Eternal Regret

advertisement