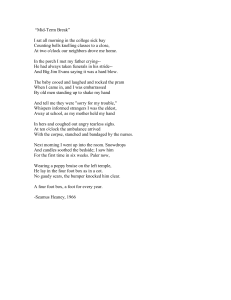

seamus heaney - Queen's University Belfast

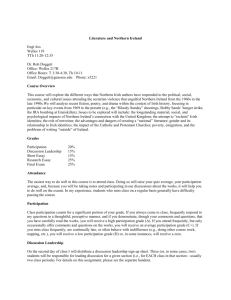

advertisement